1 April 2023

How a golf ball fooled scientists to become the world’s rarest fungus

Seventy years ago, a golf ball was officially described as a new species of fungi. Today, it lives on as one of the world's greatest Fungarium hoaxes, but should it remain within Kew's collections?

Entering Kew's Fungarium is like stepping into a secret lair. Hidden underground, shrouded in secrecy, and protected by visibly imposing concrete walls – it's a treasure trove of oddities and rarities, and a place that appeals to those with a taste for the unusual, the mysterious, and the obscure.

But things only get stranger when you take a closer look at some of its specimens.

Seventy years ago, one such specimen seemingly fooled all who came across it and was officially named a new species of fungus. However, there was one problem: it wasn’t a real fungus. In fact, it wasn’t a real life form at all.

Upon receiving it from an unknown collector for identification, mycologists submitted to Kew’s Fungarium a specimen that looked like a puff ball-like fungus but was instead just a burnt golf ball.

In their defense, it had been heavily burnt and so its appearance did resemble that of a common earthball (Scleroderma citrinum).

Common earthballs are often described as generally spherical and irregular in shape, ranging from white to tan or brown with a thick leathery skin. So, it’s easy to see how the burnt golf ball could be mistaken for such a species - as it inevitably was.

And so its fate was sealed, and the deceptive ‘specimen’ was submitted through the official process to become a permanent resident of Kew’s Fungarium. With only three ever known to exist, it is technically one of the world’s rarest fungi – an unofficial title it still holds to this day!

But how did this happen? And why is it still legally considered an actual species?

From fairway to Fungarium: How the golf ball entered our collection

Not much is known about its origins. No name or letter was found to accompany the submitted ‘specimen’. However, one thing is clear from the almost illegible writing scrawled across the golf ball’s envelope: it arrived from Lancashire in 1952.

Records show how it was soon identified by several collectors who, showing “praiseworthy modesty”, had chosen to – perhaps wisely – remain anonymous.

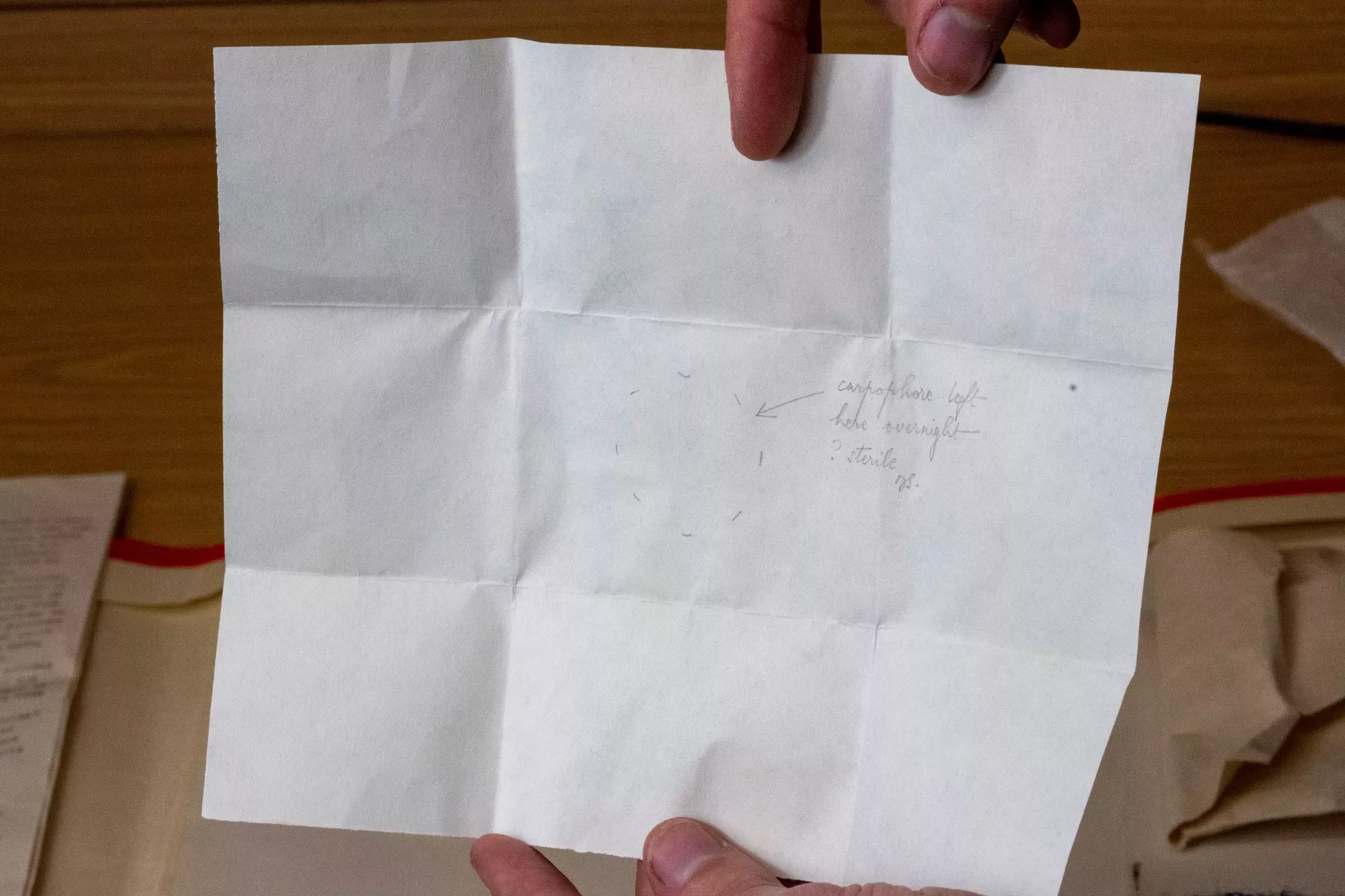

As part of this identification process, mycologists look for spores as their colour can be an important characteristic for the fungus' identification. The simplest test for this consists of placing the specimen on a blank piece of paper overnight and, by the morning, carefully removing the fungus to observe the spores, or lack of.

Of course, no such thing was observed for our golf ball. It was reported that the “spores have not been recovered and the means of reproduction therefore remains unknown.”

It’s difficult at this point to understand how anyone could think it was a real fungus. However, the dark gleba (interior) of the common earthball is strikingly similar in appearance to that adopted by the scorched inner core of a golf ball.

Did they know all along?

A decade after the first golf ball was submitted to our Fungarium, another arrived, this time all the way from East Africa.

Interestingly, an article was then published in the Journal of the Kew Guild that same year in 1962 that dropped subtle clues that strongly implied the mycologists were in on the joke the whole time, or at least had caught on quickly.

Dr R.W.G Dennis (Head of Mycology here at Kew at the time) submitted the article entitled “A Remarkable New Genus of Phalloids in Lancashire and East Africa” that seemed to describe the discovery of a new species submitted to the Kew Fungarium.

The first clue came from the description of its appearance. The article stated that the species closely resembled certain “small, hard but elastic, spheres enjoyed by the Caledonians in certain tribal rites”. This was likely a finger pointed towards the popular golfing scene within Scotland.

Another nail in the coffin comes from Dr Dennis when he described the ‘specimens’ odour as like that of “old or heated India rubber” - likely referring to the scorched elastic strands protruding from the golf ball’s inner ‘gleba’.

The punchline, however, comes at the end of the article where the species is formally described and given the name Golfballia ambusta, Latin for ‘burnt golf ball’.

It’s theorised that Dr Dennis may have officially described the golf ball to challenge the criteria in place at the time that could allow a non-life entity to be so easily submitted as a species.

The hoax collection grows – but should they remain?

The plot thickens another ten years later when, in 1971, another burnt golf ball arrives in Kew’s post. This time, the Golfballia ambusta specimen was found in Kent and, despite clearly stating that it was found “at edge of a fire site”, it is still added to the growing collection.

Was this to keep the running inside joke alive? Perhaps to purposely create what could now be considered one of the greatest hoaxes in Fungarium history? We’ll never know for sure, but what we do know is that – to this day – the golf balls are still fooling people who find Golfballia ambusta within our database and believe it to be a real species of fungus.

This begs the question: should they be removed from our collections?

This would avoid any future confusion, but would also strip away part of our Fungarium’s colourful past and the golf balls of their noble title that they’ve held for over 70 years.

‘Fore’ vs against - what our scientists say

Nathan Smith, past Fungarium Operations Manager at Kew, recently had a paper published on Golfballia ambusta that explores what defines a fungus species. For us, he plays devil's advocate and puts across the argument for removing it from our collections:

“I think Golfballia ambusta is a fantastic story and one that has real impact on how we understand, or perhaps misunderstand, what makes a species. It’s also a very funny joke that gently ribs mycologists who perhaps take themselves too seriously. However, a joke is only funny as its audience finds it to be. History is littered with jokes that have lost their meaning as language, society, and people’s tastes change and evolve. Increasingly, I fear, Golfballia is joining this growing pile of jokes.

It’s almost cliché to talk about how taxonomy is in crisis — fewer people being involved in the field means a lot of its stories are gradually being lost and this results in a type of disciplinary memory loss where the context of events such as the description of a golf ball as a fungus is lost into the ether.

Furthermore, on a more conceptual level, whilst the DNA-age has brought about many benefits, it has also led to a simplification of the understanding of species. Many people today, including many scientists, would define a species as something that is genetically-different from something else but not really interrogate what this means. These factors can mean that Golfballia stops being funny and just becomes confusing — particularly when kept amongst a large collection of genuine specimens, such as in the Kew Fungarium.

Whilst it wouldn’t solve all the problems, I would be tempted to take the specimens out the Fungarium and put them somewhere on display somewhere. Unlike the specimen itself, I think the joke does have faint signs of life — it just needs the right environment.”

Our Fungarium Collection Manager Lee Davies makes a compelling case for keeping it in:

“Golfballia occupies a miniscule amount of space in our Fungarium; three specimens out of 1.3 million. It was originally sent in as a serious identification enquiry, so has a degree of validity for keeping it in.

‘Joke’ specimens in natural history collections are common, often arising from objects sent in to be identified, and curators occasionally keeping them. They are fun, can be useful and can be used to entertain visitors.

It’s also worth noting that Golfballia has now been formally accessioned into our collection, so from a legal point of view, it falls under Kew’s obligations to look after and maintain it as part of the national collection.

To get rid of it would require a formal de-accession process - which we generally don’t do with our collections.”

A fungal legacy that lives on

So, it’s likely that the golf balls will stay for now and remain as just one example of an oddity uncovered by our Digitisation Team who are capturing our entire Herbarium and Fungarium collections to make them freely accessible online for all around the world.