13 January 2023

5 ways digitising Kew’s specimens can help save the world

From combatting climate change to producing better medicines, here are five ways our multi-million pound Digitisation Project will help ensure the future of all life on Earth.

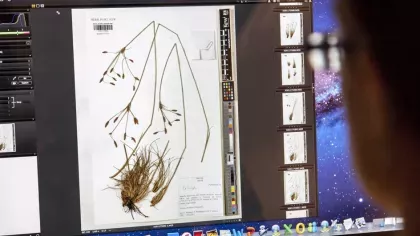

An ambitious project to digitise Kew’s entire collection of more than 8 million plant and fungal specimens is opening up a treasure trove of information that will help scientists understand and protect the natural world.

By making specimen records and images freely available online, researchers around the world can access taxonomic, habitat, and geographical data they could otherwise only get by visiting Kew in person.

Here are some of the ways Kew’s burgeoning digital resource will contribute in the battle to conserve biodiversity – and help improve the well-being of people:

1. Combatting climate change

Understanding plant ecosystems is crucial in preparing for a warmer world and protecting humankind from its severest impacts.

We know that rising global temperatures and extreme weather events are placing unprecedented pressure on plants and fungi, many of which we rely on for food, medicine and materials – but working out exactly how this affects individual species in specific locations is extremely complex.

The deep historical roots of the specimens in our Herbarium, which go back three centuries, mean they can shed light on how the spread of species from giant trees to microscopic fungi have changed over the years.

Effectively, scientists can travel back in time to see how plants and fungi were distributed in the past.

This allows them to reconstruct the extent of forests and other ecosystems that may have since been damaged by climate change or human activity.

This is vital information for researchers seeking to unravel the role of plants in the global carbon cycle and learn more about how different plants fare under different conditions.

The insights provided from analysing our digitised herbarium specimens will help in the development of strategies for preserving or restoring those plants that can help mitigate the impact of climate change.

2. Saving species from extinction

An estimated 40% of the world’s plants are now threatened with extinction – a jump from one in five plants thought to be at risk in 2016 – and researchers fear the world may be losing species more quickly than science can find, name and study them.

Knowing which plants and fungi are under threat is essential to halt biodiversity loss and preserve the world’s “natural capital” – a resource that we all rely on, from timber to make furniture to coffee beans for our morning lattes.

Assessing the risks for each species requires detailed knowledge of the kind that can only be found by mining large datasets, like our herbarium specimens.

Analysis of information stored in our collection is already paying dividends. It has been invaluable in, for example, assessing the threat posed to some species of rosewood (Dalbergia and Pterocarpus) due to the world’s soaring appetite for rosewood furniture.

This is now helping conservationists map the changing distribution of at-risk species in a bid to save them. Similarly, specimen data has helped reveal how 60% of wild coffee (Coffea) species are now threatened with extinction.

3. Feeding our future, sustainably

Just 15 crops account for 90% of the world’s energy intake, with rice, maize and wheat making up the staple diet for more than half the people on Earth. Relying on so few crops inevitably leaves us vulnerable to climate change.

The exact implications of a hotter world are still debated, but it is clear that many staple crops could be threatened by water shortages and encroaching deserts.

This is where legumes come in.

Considered ‘the future of food’, legumes are unique in that they are both a source of protein and natural fertiliser meaning they can play a key role in improving the health and nutrition of a growing global population, while at the same time supporting sustainable agricultural practices in a warming world.

Spanning kitchen cupboard favourites such as chickpeas, lentils, soya beans and peanuts, many legumes have a vital role in human health, providing a highly nutritious source of fibre and plant-based protein.

Legumes will not be immune from the ravages of climate change but, as a family, these plants are survivors. They thrive in some of the harshest landscapes, giving scientists hope that it will be possible to breed new varieties with improved survival traits, such as drought or salinity tolerance.

Our Herbarium at Kew contains more than 7 million plant specimens, of which 10% or around 700,000 are legumes, making it one of the greatest collections of leguminous plant material in the world.

DigitIsed specimens help scientists refine the geographic ranges of plants to better understand their natural habitats and how the distribution of species has changed over time.

These insights could help us select the most resilient legume species that are immune to the effects of climate change – providing future generations with the same bean-based dishes that we know and love today.

4. Future-proofing agriculture

Delivering optimal supplies of today’s major food staples – especially cereals – in a warming world is going to be vital to ensuring food security, and it will require researchers to look beyond the established varieties of grain that dominate modern agriculture.

Our historical collections are being leveraged to understand how wheat (Triticum) has evolved with changing environmental conditions and agricultural practices, and to identify useful genetic diversity for the future.

This could include resilient or nutritious wild varieties as well as valuable features of cultivated wheat that may have been accidentally lost by farmers over millennia of plant breeding in the selection process for other traits.

For many years, the genome of wheat, which is exceptionally large, was considered too difficult to be sequenced and assembled. Now, however, a reference genome has allowed scientists to understand for the first time how wheat varieties differ genetically across the world and how that affects their success.

5. Better medicines

Plants and fungi have long been used as medicine, giving the world treatments like cancer-fighting drugs vincristine and etoposide, the painkillers morphine and aspirin, the heart condition drugs digoxin and warfarin and a range of antibiotics.

But the natural world is still a largely untapped resource, with around 4,000 species of plants and fungi being scientifically described for the first time every year. Understanding more about different species is a vital first step in developing new therapeutics in the future.

Our Fungarium, which houses 1.25 million dried specimens of fungi from all continents on Earth, is a particularly rich hunting-ground since it is the largest of its kind in the world.

It contains specimens of great scientific and historical significance, such as subcultures of Alexander Fleming's Penicillium, as well as fungi collected by eminent 19th century explorers, including Charles Darwin.

Today, researchers can use the latest tools to analyse these specimens, including extracting DNA to find useful traits for new medicines.

As you can see, the real-world impact of our collections is vast, permeating into most facets of our lives and ultimately playing a key role in ensuring the future of all life on Earth.

Digitising these dried specimens will only accelerate this impact, especially once we have them all freely accessible in our new Data Portal, planned for release at the end of September 2023.