8 October 2022

Digitising Kew’s fungi collection

Discover how Kew's world-class fungal collections are going digital to help researchers across the world

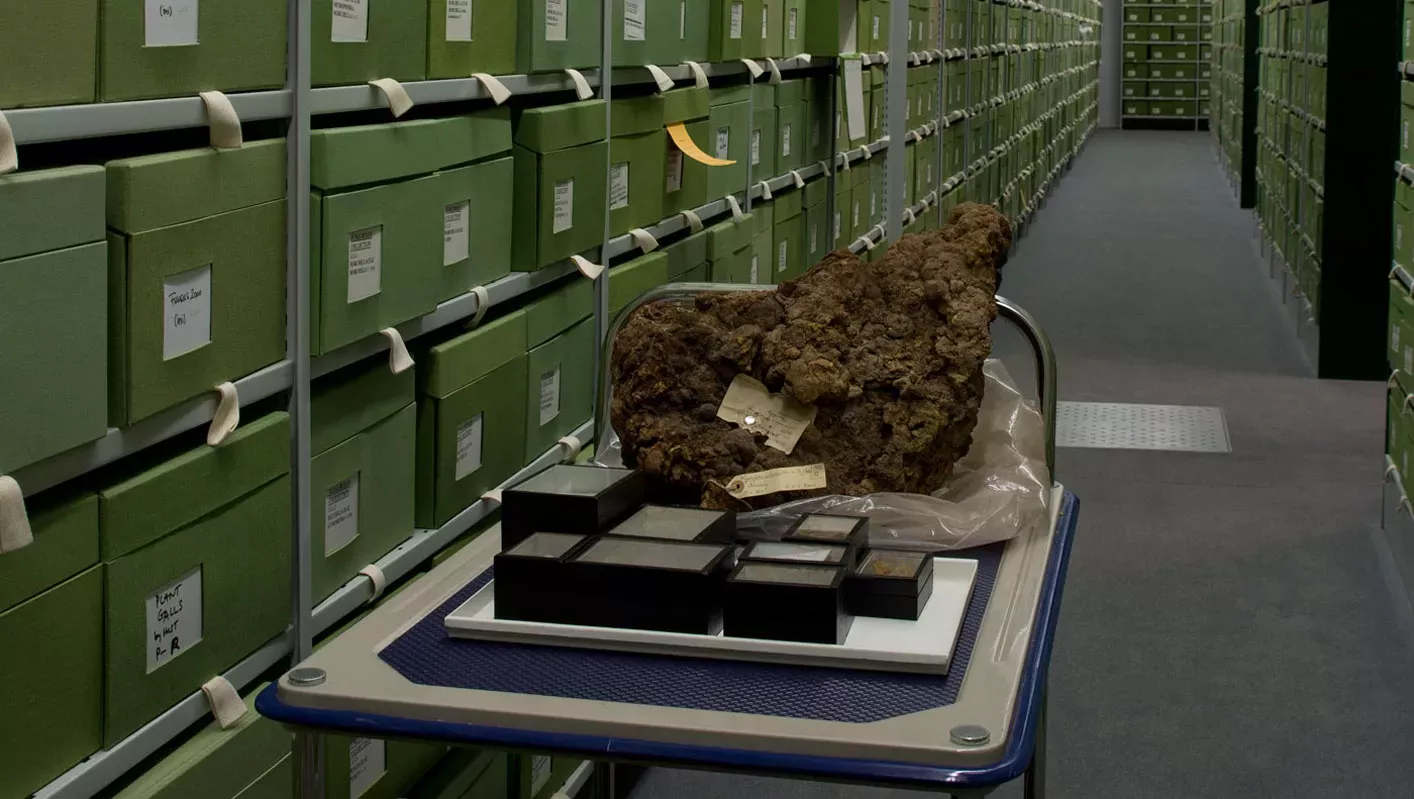

We are currently digitising our large and varied collections, made up of over 8.5 million specimens.

Amongst these are a collection of fungi, known collectively as a Fungarium.

Kew is home to one of the largest and most historically important fungaria in the world, so digitisation will open up new avenues of research to global scholars.

As digitisation of our fungi collection kicks into full swing, Kew's two Fungarium Digitisation Officers, James Whittaker and Emily Lee, give their first impressions and explain the importance of their work.

Welcome to the Fungarium

Kew’s Fungarium collection is home to over 1.25 million dried specimens of fungi from all continents on Earth. The oldest specimens date back to the early 18th century, many of which are of great scientific and historical significance – such as the subcultures of Alexander Flemings’s Penicillium.

We are also proud to have fungi collected by John Ray, Charles Darwin, Alexander von Humboldt and many other famous naturalists around the world.

Our specimens help us identify and describe species that are yet unknown (which is approximately over 95% of all fungal species). They also allow us to investigate the interactions between and distribution of plants and fungi, as well as understand and analyse the impact of invasive species, pathogens and climate change.

Just like plants, fungi are tied to all life on Earth.

The British National Collection at the Fungarium holds around 380,000 specimens from the UK. Collections from other parts of the world focus on historically significant collectors from the 19th century. Specimens from the International Mycological Institute are stored alongside the Kew collection and are particularly significant for tropical plant pathogens.

James’ take on the Fungarium

'Having only recently started working at Kew’s Fungarium, there is still much to learn and do, but I am fascinated and motivated by what I have seen so far!

The Fungarium is every bit as engaging as the Herbarium – and the sheer range and number of different species make it a privilege to work in.

The first specimen that I handled as part of my work at the Fungarium was a sample of Aquascypha hydrophore, which is the only one of its genus. It resembles a conical cup and originates from the rainforests of Central and South America.

This species evolved a cup-shape to collect and hold rainwater on the forest floor. Aquascypha fungi thus became habitats for insects like mosquitoes. The specimens that were mounted and preserved display this feature, which makes them instantly recognisable and fascinating to examine.'

Emily’s take on the Fungarium

'Before I stepped into the Fungarium for the first time, it was a mysterious big treasure vault of knowledge to me, and it still is.

Fungi are everywhere around us, yet I know so little about them. They come in such a vast variety of shapes and sizes, sometimes creepy, sometimes enchanting, always reminding me of the power and mercy of nature, and how organisms manage to find such interesting ways to survive.

I feel very privileged to be working here, to be able to handle all those wonderful specimens of the past, as well as to look at the collectors’ notes and letters which endured through history to tell stories, to describe lives.'

Hats off to fungi

One specimen that Emily came across was an amusing species - Pilobolus crystallinus, also known as the ‘dung cannon’ or ‘hat thrower’.

These small fungi look like glittering bits of crystal, but in striking contrast to their beauty, they are always found growing on animal dung, as their spores attach to vegetation grazed by animals, allowing the fungi to grow in nutritious faeces.

Although these fungi only grow up to 2-4cm tall, they can shoot their sporangium (a structure containing their spores) up to 2 metres away. The sporangium accelerates at such a high speed, it’s like launching a human at 100 times the speed of sound! It can then stick itself wherever it lands using a mucus-like substance.

Digitising the Fungarium

Our work at the Fungarium is just one part of Kew's Digital Revolution, the ongoing digitisation project across our collections.

Digitising fungal specimens works just the same as digitising the plant specimens. First, barcoding and basic data entry of the sheet-mounted specimens. Then, the specimens are photographed, before finally both the images and their metadata are uploaded to the database.

The digitisation process of Kew's collections will happen over a projected period of four to five years. It will be a long and challenging process, involving imaging and processing a huge number of diverse specimens and material.

Why go digital?

Digitisation is important for any collection, museum or archive, as it creates a permanent digital record of physical material collections.

Specimens, paper records and objects can degrade over time, or could be lost in a catastrophic event. Imaging them today preserves them in digital form, for much longer than their physical existence.

Another benefit is improving access. Our collections and records are highly sought after by researchers, not all of whom will be able to access them in person.

A digitised collection can be accessed online for free by researchers from anywhere in the world. It helps make research more efficient by sharing our knowledge with as many people as possible.

So far, Emily and James have been well-introduced to the intricacies of the Fungarium’s archive and reference system. They are trained on the camera station within the Fungarium

In the future, they’ll continue building on their experience and confidence, and help bring the Digital Revolution to Kew’s Fungarium.