14 October 2022

Weird and wonderful fungi

Meet some of the strangest members of the fungi kingdom.

Scientists have identified nearly 150,000 species of fungus across the world. It might seem like a lot, but really, it’s just scratching the surface.

There could be over three million different species of fungus, meaning we’ve only identified less than 10% of the whole kingdom.

But why is it so important that we know what’s out there in the world? Why do fungi matter?

Keeping the cycle going

One of the key roles that fungi play in the ecosystem is as rotters: they break down and decay organic matter into carbon, which is then returned to the environment.

Many fungi are referred to as ‘saprotrophs’, which literally means ‘eaters of rot’. Instead of digesting their food internally, fungi produce chemicals to digest their food in the environment, and then absorb it.

When you see a fallen tree covered in fungi, they will be secreting chemicals to break down lignin (the material that makes up bark and wood). Fungi also grow on leaf litter and organic matter in the soil, helping to return carbon into the soil, where it can be reabsorbed by themselves, as well as plants.

You might be familiar with some of these saprotrophic fungi — the redlead roundhead (Leratiomyces ceres) is a common site across the UK, thriving on wood debris and lawns. You may have also spotted the shaggy ink-cap (Coprinus comatus) growing in so-called ‘fairy rings’ on grass fields.

Both of these species of fungus are crucial players in our ecosystem, keeping the carbon cycle moving forward.

I stink, therefore I am

You might also be familiar with fungi from the Phallaceae family, better known as the stinkhorns.

Not only do they have a unique shape, but stinkhorns produce a scent that is compared to rotting meat, similar to the titan arum or the Rafflesia.

The common stinkhorn (Phallus impudicus), like many of the stinkhorns, has a cap known as the gleba. This cap produces a sticky slimy substance which contains the spores of the fungus, along with that signature rotten meat smell.

This helps attract flies and other carrion insects to the fungus in a sneaky bit of scent-based subterfuge.

When the flies land on the gleba, the sticky slime attaches to their legs. The insects then become unwitting couriers, to help spread the spores further afield than the wind alone.

Other species of stinkhorn fungus have even more strange structures, along with their putrid stench.

The veiled lady fungus (Phallus indusiatus) grows a long ‘skirt’ from its cap, to protect the spores before they are ready. Whilst the octopus stinkhorn (Clathrus archeri), also known as ‘devil’s fingers’, bursts red tendrils from white, egg-like structures like something from a science fiction movie.

Glow in the park

It’s not just smells that fungi can use to attract potential spore couriers.

Just over 100 species of fungi are known to bioluminesce: they can produce light through a chemical reaction in their cells.

Science doesn’t fully understand the chemical process behind bioluminescence in fungi, although the evidence suggests it’s similar to how insects like fireflies do it.

We’re also not exactly sure why a fungus might need to produce light, but one of the lead theories is that it helps attract animals that could be potential spore spreaders. On the other hand, there’s also a theory that the light actually puts off any peckish animals that might fancy a midnight mushroom snack!

Potentially the largest single organism in the world, the ‘humongous fungus’ found under Malheur National Forest in Oregon, USA, is an Armillaria ostoyae, which is capable of bioluminescence.

Farming fungi on the sea shore

With fungi being such a key part of our ecosystem, it’s no surprise that they aren’t just found on the land, but also in our oceans.

Fungi have been discovered in almost every single marine environment, from coral reefs to deep within ocean sediments.

Unfortunately, because it’s incredibly difficult to grow these fungi outside of the ocean, we know very little about them. Just under 450 species of marine fungi are known to science, but there’s almost certainly thousands more to be discovered.

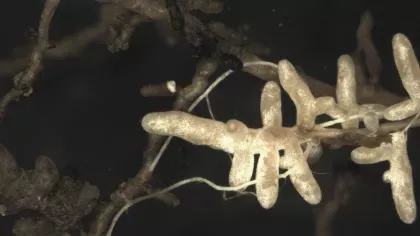

The marsh periwinkle (Littoraria irrorate) lives in coastal sea marshes, where it helps cultivate fungus to feed on. The snails damage cordgrasses (Spartina), which allows fungal spores from the Phaeosphaeria and Mycosphaerella genera to colonise and begin to grow. The snails then feed on the fungus, which is far more nutritious than the grass itself.

Fungal diseases are also found in certain sea creatures, including lobsters, whales and dolphins, although very little is understood about them.

With potentially millions more species currently unknown to science, this really could be just the tip of the iceberg. There are so many incredible species yet to be discovered.

Join us next time when we explore how some of these fungi might one day help save the world.