5 December 2023

Unearthing the untold stories behind Darwin’s specimens that shaped evolution

Kew’s Digitisation Project is prompting fresh study of Charles Darwin’s plant collections from his famous trip aboard HMS Beagle.

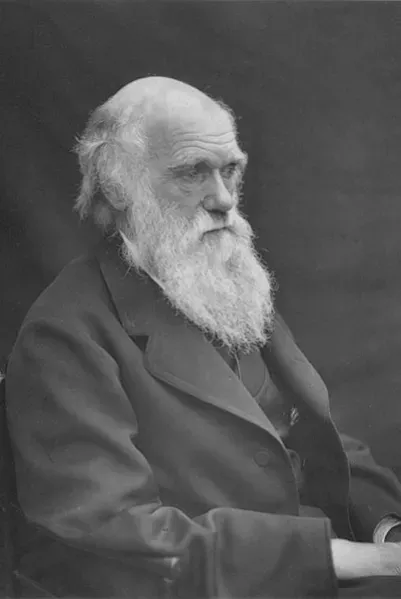

Nearly two centuries after the 22-year-old Charles Darwin set off on his round-the-world trip aboard HMS Beagle – a voyage that inspired his view of evolution – the plant specimens he collected are still yielding insights and remain a live area of curatorial research.

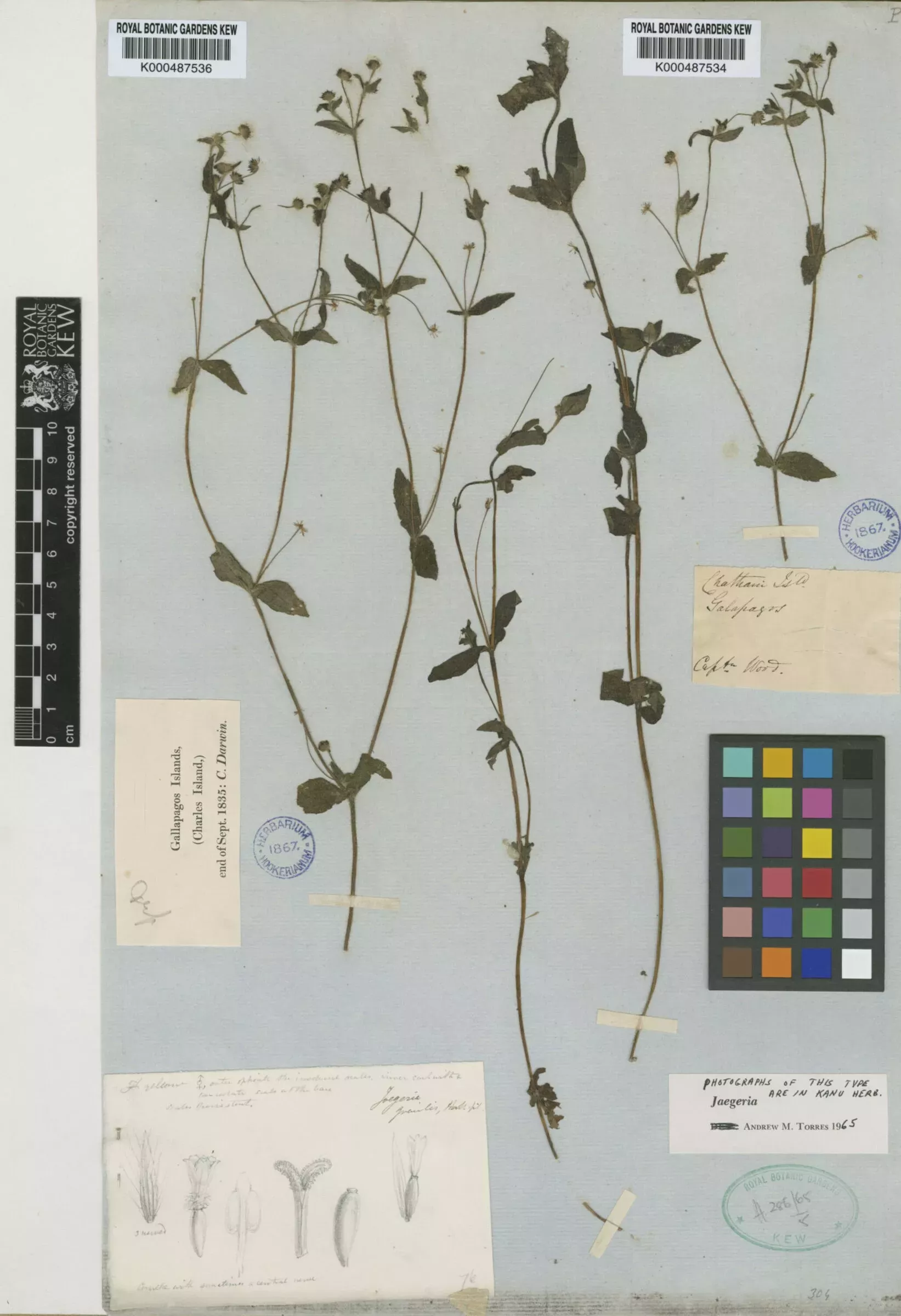

Kew’s Herbarium – one of the largest in the world – is a major centre of Darwin’s plant collections. Of the 1,400 plant specimens that Darwin collected aboard HMS Beagle, around 450 specimens are housed at Kew, with the top set being located at Cambridge University Herbarium.

What’s in our collection of Darwin specimens?

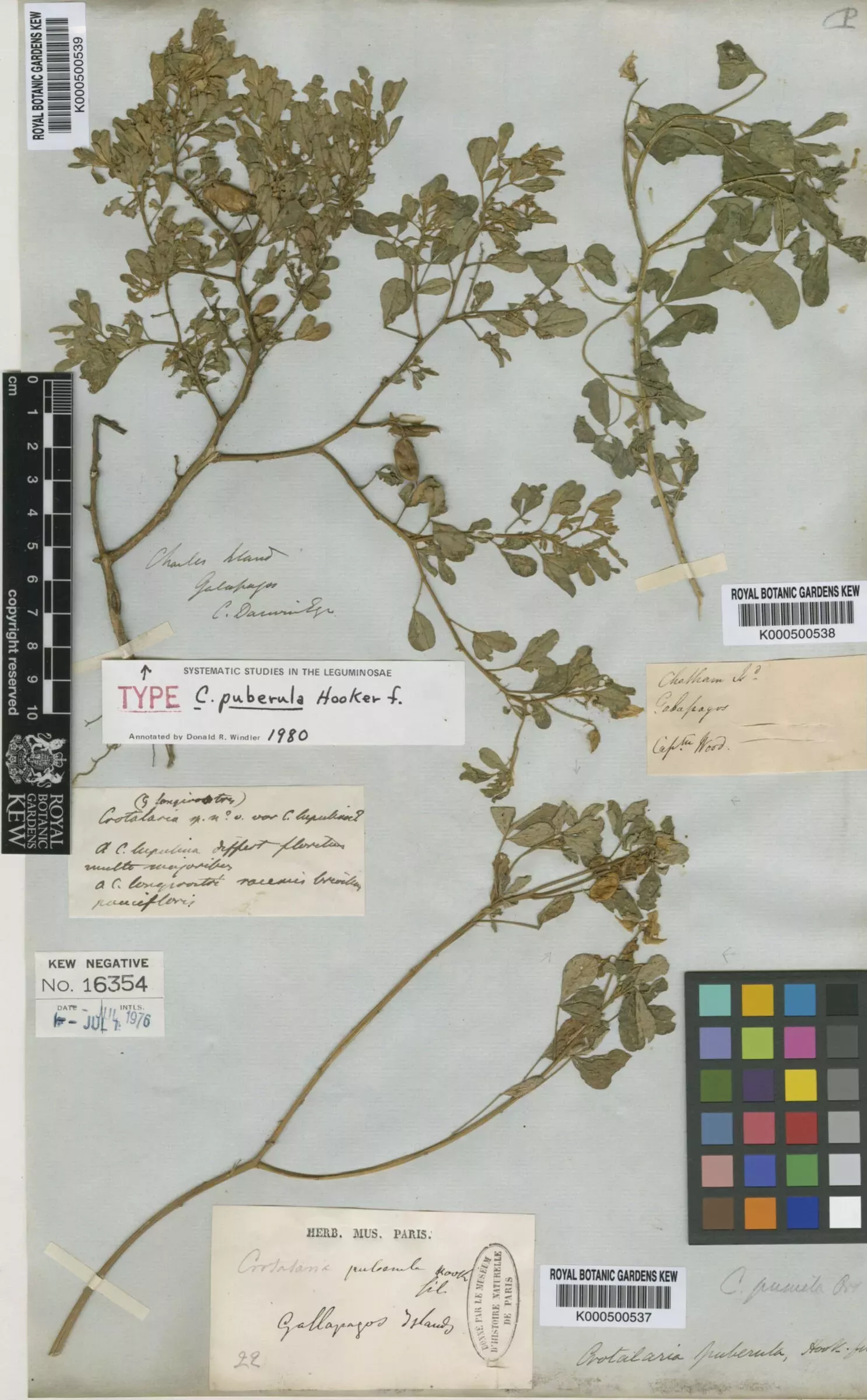

Kew’s collection represents 75 plant families, collected by Darwin from places such as the Galápagos Islands, Tierra del Fuego and the Chonos Archipelago in Chile.

But because new information on who collected which plant is continually emerging as more specimens are imaged, digitally catalogued and made available online via our Digitisation Project, no-one knows for sure the full tally of Darwin specimens.

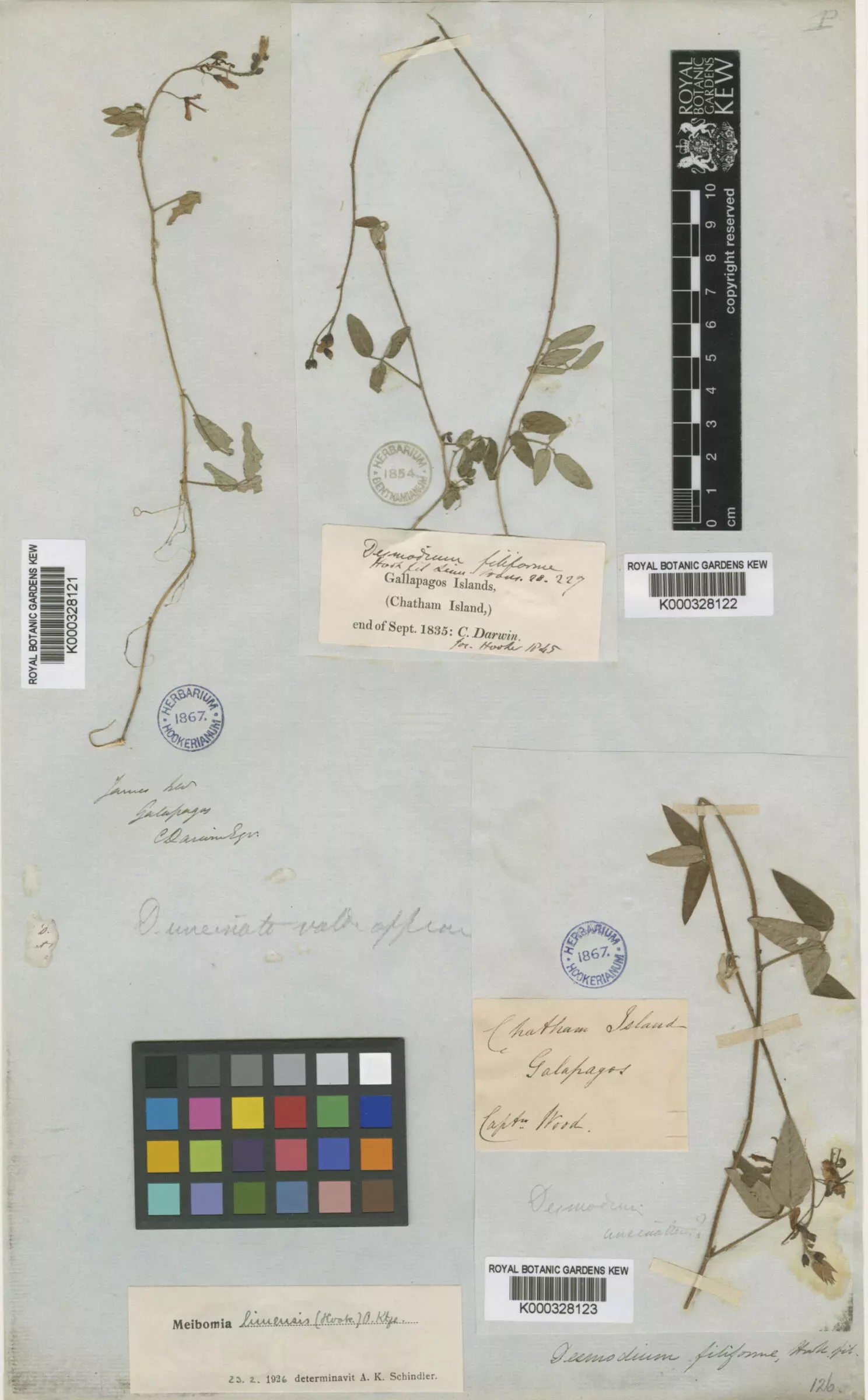

The task of identifying every single plant collected by Darwin, or any Victorian-era collector, is made more challenging by the fact that it was common practice at the time to stick multiple plant specimens on a single herbarium sheet.

This creates problems since sheets have to be filed according to only one of the taxa present, so any material attached to an unrelated specimen is very difficult to locate again.

Now an ambitious project to digitise Kew’s entire collection of more than 8 million plant and fungal specimens is shining a spotlight on some hidden corners of this unique botanical archive.

Rediscovering historic specimens

In the process, scientists are uncovering specimens from early collectors that have lain unnoticed for years. Whether this will include unknown treasures from Darwin remains to be seen.

It all means that while the voyage of the Beagle entered the history books long ago, Darwin’s plant collections are subject to continuing investigations and some uncertainty.

What is not in doubt, however, is the historical and botanical importance of the specimens he collected as the Beagle travelled across the Atlantic, around South America and back to England via the Pacific on its voyage of exploration for the British Admiralty from 1831 to 1836.

How Darwin came to the theory of natural selection

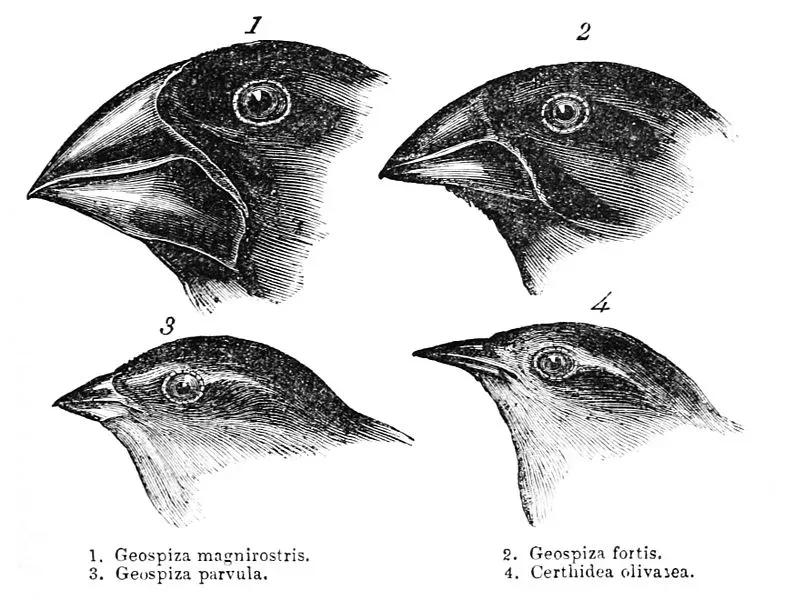

Of particular significance are the large number of specimens from the Galápagos Islands, where Darwin found that species of plants and animals differed from island to island, even though many of the islands were not far apart.

It was while pondering this that Darwin started to form his revolutionary ideas on the evolution of life on Earth and the notion that one species could give rise to multiple species, each exploiting different niches.

Darwin was famously inspired by the adaptive evolution of Galápagos finches, which have different beaks from island to island, but plants also played a crucial role in developing his theory on the origin of species.

In the process of collecting a wide range of plant species, he created an invaluable botanical resource that remains foundational to the modern understanding of the area’s fragile ecology.

Before Darwin visited in 1835, very little was known about the range of wildlife on the Galápagos Islands and his visit was transformational. After five weeks of hard work, his collecting efforts had covered an estimated 24% of all the islands’ flora known today.

The role of plants in Darwin’s theory

Cataloguing and understanding the significance of what he had found was a lengthy process and would take another decade to reach fruition.

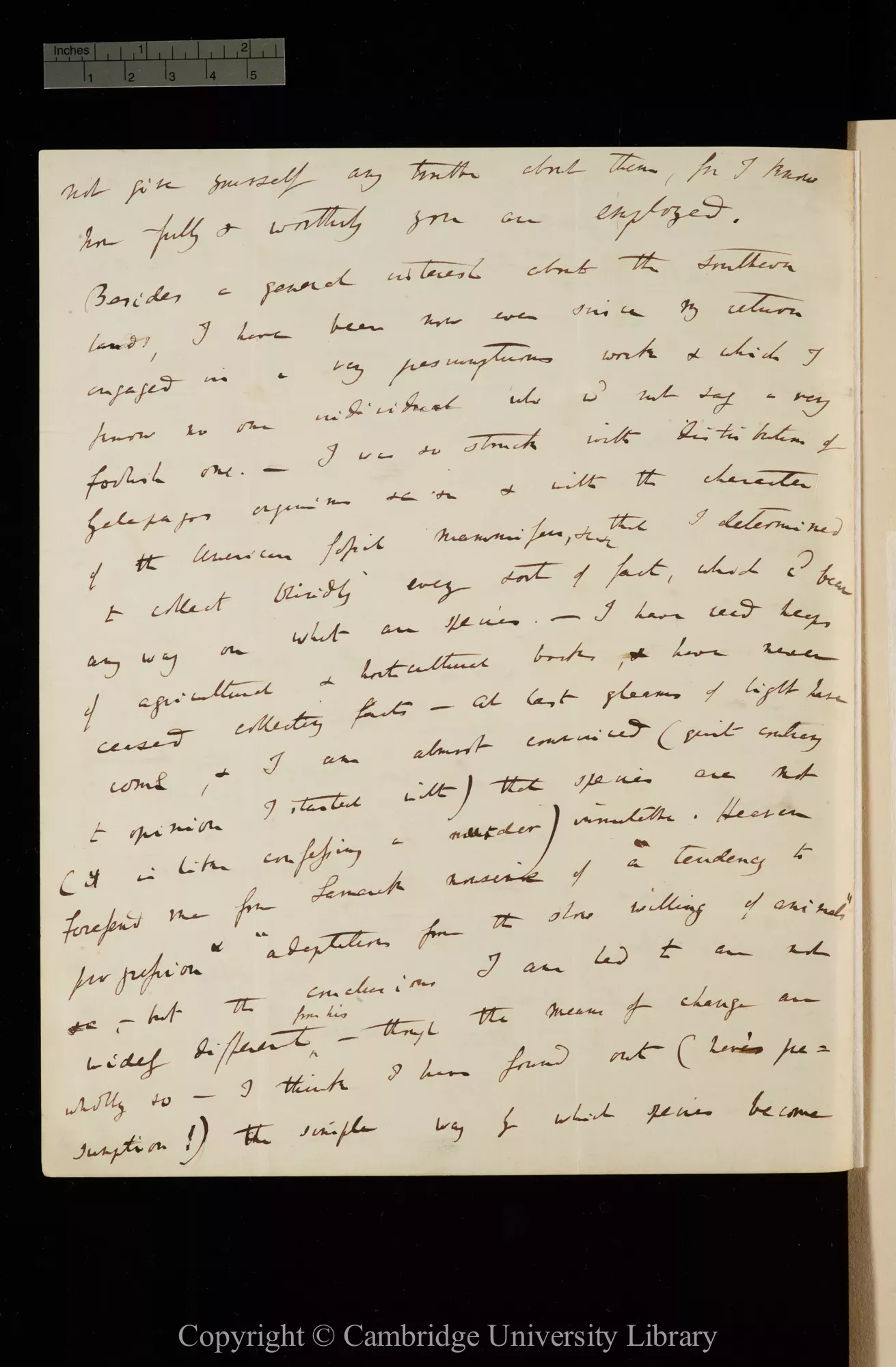

Darwin carefully packed and sent home specimens from the Beagle to his mentor Professor John Henslow in Cambridge, and the two men exchanged letters in which Darwin expounded his developing theories. Kew’s Archives contains 44 of these letters. Plants would later emerge to have a pivotal role in developing Darwin's theory of natural selection.

Henslow's innovative teaching methods, including the use of herbarium collections and illustrated lectures, exposed Darwin to the intricate patterns of variation within plant species.

Darwin's plant collections from his transformative voyage, sent back to Henslow, laid the foundation for his understanding of populations and variation within them.

These early botanical explorations, guided by Henslow's mentorship, subtly foreshadowed the evolutionary concepts that would later revolutionise biology.

It was not until 1843 that the young Joseph Dalton Hooker, son of the then director of Kew Gardens, agreed to examine Darwin’s Galápagos plants in detail.

Charles Darwin and Joseph Hooker discuss Darwin's findings

Hooker presented his findings to three meetings of the Linnaean Society in 1845, describing dozens of new species and concluding that more than half of the Galápagos plants were not found anywhere else in the world. In other words, they were endemic – and, in many cases, restricted to individual islands.

Hooker and Darwin, who became close friends, engaged in a lively correspondence over the Galápagos plants as Darwin honed his theory of evolution.

Famously, it was in an 1844 letter to Hooker that Darwin first confided his conviction that species were not immutable, adding that saying as much was “like confessing a murder”.

Of particular interest to Darwin and Hooker were plants in the Asteraceae family because of the great number of endemic genera and species in this group.

Several of these plants feature prominently in the Kew Herbarium – and the botanical family is also at the centre of modern-day efforts to protect the delicate flora of the Galápagos.

Conservationists are concerned about the archipelago’s dwindling forests of Scalesia, a genus of Asteraceae that forms giant daisy trees. The plants are unique to the Galápagos and each of the species shows remarkable adaptation to the growing conditions across the different islands.

Sadly, they are now being threatened by deforestation, climate change and the spread of invasive blackberry plants, which block the next generation of trees from growing.

Accelerating science using Darwin's specimens

Today, a key focus of the Charles Darwin Foundation in the Galápagos is saving the Scalesia cordata species, a tree endemic to the southern part of the island of Isabela that is on the brink of extinction.

Our Digitisation Project at Kew is largely in its infancy with another six million specimens to digitise by 2026, which means a treasure trove of plant specimens – and their secrets – are still to be unearthed, but we can't do this without your help.

See the exciting opportunities below that will allow you to help immortalise our collections for current research and future generations to help combat our greatest challenges, including climate change and biodiversity loss.

Help us digitise our prestigious collections

Get involved with these new opportunities

-

Volunteer

Become part of Kew's ambitious project and help make one of the largest collections in the world freely accessible to everyone around the world.

-

Donate

Donate today and immortalise a piece of botanic history that can aid research into urgent global challenges - helping protect our planet for future generations.

-

Join

See what job opportunities are available to digitise our collection and play a part in helping scientists across the world access our invaluable specimens.