11 January 2024

Kew’s top 10 new species of 2023

Kew’s scientists and international partners share their 10 favourite new species named to science in 2023.

It’s been another excellent year! In 2023, 74 plants and 15 fungi were named by botanists and mycologists here at Kew and at our partner organisations around the globe.

We've seen everything from microscopic fungi growing on lichens in Antarctica, to a towering giant tree in Cameroon’s cloud forest, weighing in at 7-8 tons.

Why does it matter that we identify new species?

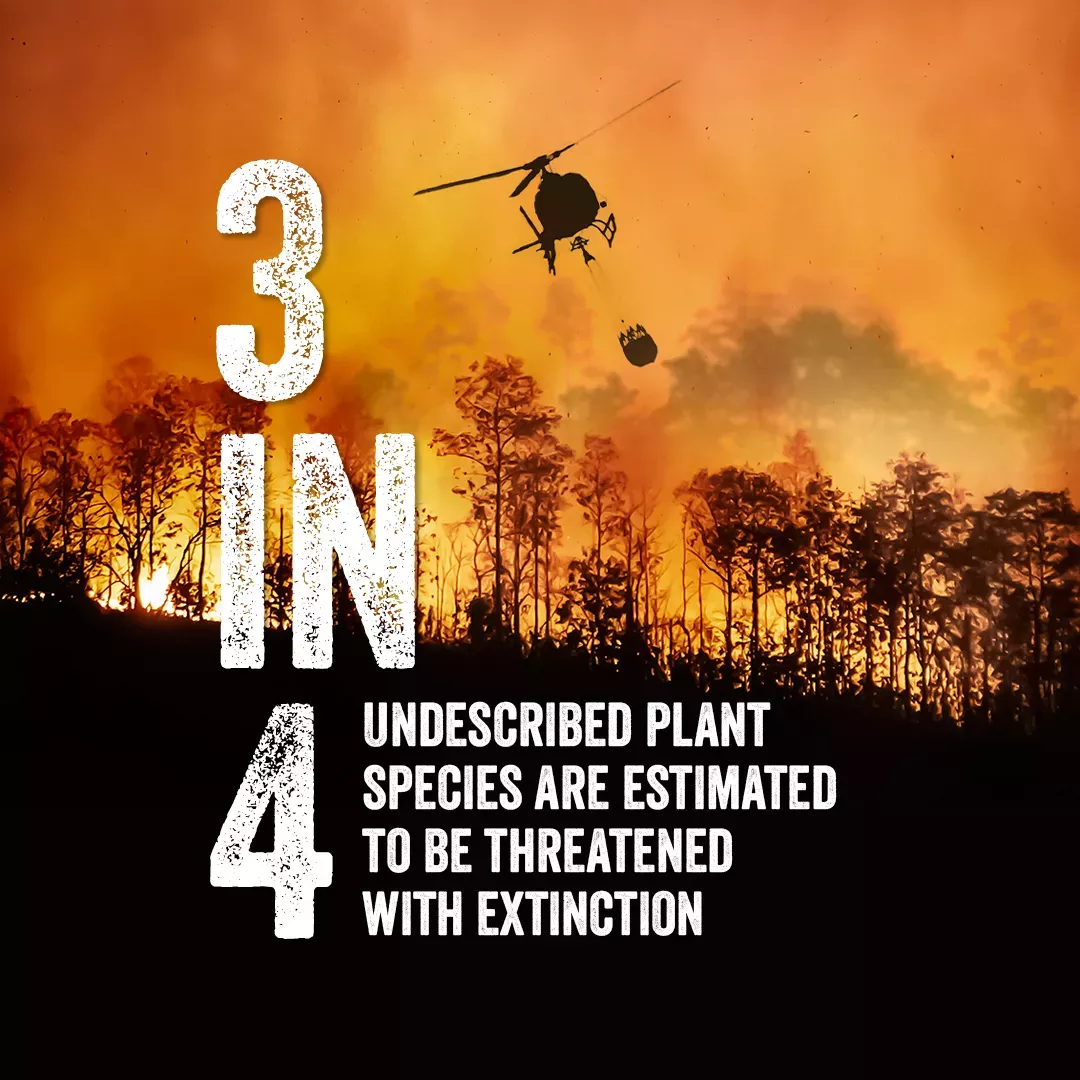

We saw in this year’s State of the World’s Plants and Fungi report that three out of every four undescribed plant species are threatened with extinction, while there are likely more than 2 million species of fungi left to discover. Many of the new species we’re seeing are known by only a single surviving individual. Others we find in an area of habitat set for destruction. But there’s also much to be optimistic about.

With our international partnerships we’re protecting new species wherever we can, whether that’s by incorporating their habitat into our network of Important Plant Areas or by conserving their seeds through the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership at Wakehurst. We have ways of saving the most threatened new species arrivals, but only if we can find them in time.

This year’s list celebrates extraordinary diversity in the wonders of nature that have been found, the people who have found them, and the information that can help us ensure these new wonders aren’t lost.

Let’s take a look.

1) The orchid saved by a bird – Aeranthes bigibbum

A tiny reserve in Madagascar is maintained by a group of Malagasy villagers with the hope of protecting the Endangered helmet vanga (Euryceros prevostii), a stunning blue-beaked bird. Visitors flock to glimpse a sight of this rare animal bringing income to villagers and incentivising the forest’s protection.

It’s in this tiny patch of forest that Kew’s Johan Hermans and his Malagasy botanist collaborators found A. bigibbum, an epiphyte orchid that spends its life growing atop other plants.

Were it not for the care and love for a unique bird, it’s likely this forest would’ve been gone long ago, taking its plant life with it. Care for one species can protect countless others that share its home.

2) Underground trees of Angola – Baphia arenicola and Cochlospermum adjanyae

So much life makes its home underground. Plants are no exception.

During a National Geographic Expeditions survey of remote Angola, Kew’s Dr David Goyder found two new tree species buried in the Kalahari sands. Trees known to this region have as much as 90% of their body mass deep under the surface.

Baphia arenicola belongs to the bean family and is named literally “growing on sand”, while Cochlospermum adjanyae is named for Adjany Costa – an Angolan colleague recognised for her achievements with the 2019 UN Young Champions of the Earth Africa prize.

3) Not such a dangerous fungus after all – Lichtheimia koreana

Of the six Lichtheimia species of fungi known to exist already, three can cause unpleasant human diseases from lung infections to serious skin lesions.

We’re thankful then the latest addition to this genus, found in soy waste across multiple South Korean provinces by Kew mycologist Dr Paul Kirk, is not so related to its pathogenic cousins and poses minimal health concern.

L. koreana’s relatives have been found across the globe – in soil, food products, invertebrates and even faeces. Often we find something we don’t yet fully understand in the most unexpected places.

4) An orchid living atop a volcano – Dendrobium azureum

A scientific expedition to the volcanic Indonesian island of Waigeo hoped to rediscover a long-lost blue orchid (Dendrobium azureum) last seen more than 80 years ago.

This they did, on the very summit of Mount Nok! Not only this, the team, including Kew’s Dr André Schuiteman found multiple previously unknown orchid species as well.

One new find was Dondrobium lancilabium wuryae (a new subspecies of D. lancilabium), an orchid with spectacular red flowers named for Mrs Wury, the wife Ma’ruf Amin, Indonesia’s vice-president. It is the ninth new orchid from Southeast Asia to be described in the last 12 months by Dr Schuiteman and partners.

5) The palm that flowers underground – Pinanga subterranea

A tip off from Malaysian botanist, Paul Chai, to Kew’s Dr William Baker, Dr Benedikt Kuhnhäuser and Dr John Dransfield led them to one of the world’s most unusual palms. Hidden in plain sight on the island of Borneo, it is a palm that fruits and flowers entirely underground.

This highly unusual plant behaviour is only known to one other plant, an orchid called Rhizanthella.

Despite being a fascinating scientific discovery, Pinanga subterranea was nothing new to the communities living in the region. The plant has multiple names in Bornean languages: Pinang Tanah, Pinang Pipit, Muring Pelandok, and Tudong Pelandok.

Better interaction between science and the wealth of wildlife knowledge held by communities and indigenous groups holds huge potential for new scientific discoveries that might benefit people everywhere.

6) The fungi that live in Antarctica – Arthonia olechiana, Sphaeropezia neuropogonis, and Sphinctrina sessilis

When we think of the icy and barren wilderness of Antarctica, we don’t typically think of plants. Yet the cold continent is home to many species of lichens, fascinating forms of life that are a partnership between fungi and algae or cyanobacteria.

Even lichens cannot make their home on ice though. They grow on ‘nunataks’, the 2% of Antarctica exposed as bare rock. Kew mycologist Raquel Pino-Bodas joined a team of scientists investigating lichens near the Spanish Antarctic base, adding three new cold-braving Antarctic lichen species to the 100 known so far.

7) Australian tobacco in a National Park – Nicotiana spp.

One of the most famous plants, tobacco of the genus Nicotiana are scattered all over the globe, but half of its 90 species make their home in Australia. Kew’s Mark Chase and Maarten Christenhutz spend a portion of their year here, studying the DNA and taxonomy of this infamous genus, and how they survive some of the driest places on Earth.

Together they described nine new Nicotiana species in 2023, including N. olens, found on clay and sandstone, and in the Pines Picnic Grounds of Cocoparra National Park.

N. olens was previously thought to be part of similar species N. suavoeolens, a species first brought to Europe as seeds by British naturalist Sir Joseph Banks.

By studying the species already known to us as scientific techniques improve, we’re often finding new species that’ve been hidden under our noses for decades.

8) A new flowering plant on the brink – Microchirita fuscifaucia

Microchirita fuscifaucia arrives on the new species list already threatened. It’s known to just two sites in Thailand, both of which are unprotected and at risk of clearance.

The 47 known Microchirita species live a life almost exclusively atop limestone rocks, with their striking flowers of many colours and patterns. This new species is named for its charismatic dark throat.

It joins seven other species described in 2023 by former Kew scientist Carmen Puglisi, and colleagues David John Middleton, Naiyana Tetsana, and Somran Suddee of Singapore Botanic Gardens and the Forest Herbarium (BKF) in Bangkok.

9) Named for a pioneering conservationist – Indigofera abbottii.

Of the 750 species of Indigofera known to science, 80 of them owe their scientific naming to Dr Brian Schrire, a Kew Honorary Research Associate. With his co-authoring colleagues, he has named 18 from South Africa in the last year, giving him the special title of Kew’s highest scoring taxonomist of 2023.

One of the new species, Indigofera abbottii is named for Anthony (Tony) Thomas Dixon Abbott. Abbott’s work as a pioneering conservationist and amateur plant collector has made many new species finds possible. Pressure is on for this new indigo species, with clearance of habitat for agriculture and housing posing questions for the future.

10) A new carnivorous plant… or not? – Crepidorhopalon droseroides

During a botanical exploration of Mozambique, botanist Bart Wursten encountered a mysterious plant covered in insect-trapping hairs. It looked just like a sundew (Drosera), a genus famous for its trapping and consumption of insect prey.

Yet, further examination alongside Kew’s Dr Iain Darbyshire found the plant belongs to the genus Crepidorhopalon, a group of flowering plants in the order Lamiales – including mints and their relatives. In the family that Crepidorhopalon belongs to, Linderniaceae, no plant carnivory has ever been previously recorded.

Plenty of field and laboratory studies are still needed to confirm whether this new species is truly carnivorous. While we know it can attract and trap insects, whether it can digest and absorb them for nutrition is another question.

Time will tell if this is the latest meat-eating marvel of the plant world.