14 February 2017

New species roundup: Kew’s 2016 discoveries

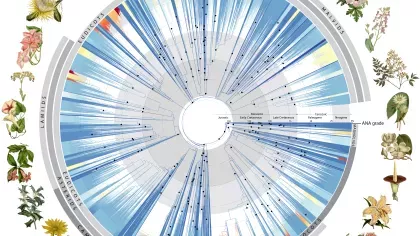

2016 saw the publication of over 450 new genera, species and varieties of fungi and plants in papers co-authored by Kew scientists and their collaborators around the world. Of these, more than 200 can be directly ascribed to Kew scientists themselves.

Fungal findings

The 22 new species of fungi published by Kew scientists included an oyster mushroom, thought to be capable of ensnaring nematodes (roundworms), currently known only from marram grass of British, French & Irish sand dunes: Hohenbuehelia bonii published by Ainsworth, Martinéz & Dentinger. This was discovered as part of the Lost & Found Fungi (LAFF) project sponsored by the Esmée Fairburn Foundation.

Five of the newly discovered species are entirely underground, truffle-like ectomycorrhizal fungi found on the roots of rain forest trees, mainly in Cameroon. These new species are in the genus Elaphomyces, and the new genus Kombocles (Bryn Dentinger and colleagues).

Meanwhile 16 species of Cortinarius toadstools were published by Tuula Niskanen and Honorary Research Associate (HRA) Kare Liimatainen: all from the deciduous and evergreen forests of northern Europe and North America. One of these species, the blue-tinted, Cortinarius jonimitchelliae was named to honour the singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell who has long championed environmental protection.

The bountiful Americas

In the Americas, HRA Terry Pennington published 37 new species of rainforest tree based on decades of research. These included 27 new Sloanea (Elaeocarpaceae) in a precursor to his planned monograph of the genus, and ten new species in his revision of the American Trichilia (Meliaceae). Terry was one of the top publishers of new species at Kew in 2016, and his MBE, announced in the New Year’s Honours list is well-deserved.

The long list of discoveries includes new genera revealed by molecular analysis, published by Gagnon and Lewis (Gelrebia, Paubrasilia, Hererolandia and Hultholia, all divided from Caesalpinia – Leguminosae), and, Sothers and Prance (Cordillera – Chrysobalanaceae, divided from Licania). Gwil Lewis also co-authored a new species of Mucuna.

Three new morning-glories (Ipomoea – Convolulaceae) and three Mimosa (with Lewis) from Paraguay, Brazil and Bolivia were published by HRA, John Wood. Also from Bolivia, a new Oxypetalum (Apocynaceae) co-authored by Goyder.

A new Myrcia (Myrtaceae) was published from Mata Atlantica by Eve Lucas and her Brazilian collaborators, while Eimear Nic Lughadha and Elizabeth Woodgyer co-authored two new Graffenrieda and a Tibouchina (both Melastomataceae) respectively.

Asian treasure-trove

Tropical Asia saw the publication of a new Areca palm from New Guinea by Charlie Heatubun (HRA). Andre Schuiteman published seven new orchids in Bulbophyllum, Dendrobium, Nervilia, Porpax, and Taeniophyllum, while Tim Utteridge and Ian Turner published three new Artabotrys and Polyalthia (Annonacae) from Malaysia. Utteridge also co-authored a new Lysimachia from Thailand, and John Wood published a new Eranthemum (Acanthaceae) from Myanmar. Alan Paton co-authored two new Scutellaria (Lamiaceae) from Burma and Thailand.

Two new Nepenthes were published from Sulawesi, Indonesia by Martin Cheek; and HRA Mark Coode co-authored a new Elaeocarpus tree. Soejatmi Dransfield published two new genera of bamboo, Ruhooglandia and Widjajachloa from New Guinea, with Wong Khoon Meng.

Abundance in Africa

In continental Africa, the discovery of Karima (Euphorbiaceae), a new genus of shrubs from river rapids, resulted from an environmental impact assessment for a planned hydroelectric dam in Sierra Leone, while new Inversodicraea and Macropodiella (Podostemaceae) from river rapids in Guinea and Ivory Coast were published.

New species of spiny tree Allophylus (Sapindaceae) found in remnants of lowland rainforest of Guinea-Liberia and Cameroon were published, along with a new climbing Psychotria (Rubiaceae) from patches of cloud forests of the Guinea Highlands. Africa’s first endemic Calophyllum (Calophyllaceae) was found in an impact assessment for a uranium mine in southern Mali; with fewer than 10 mature trees known, it is particularly highly threatened.

From Cameroon, Xander van der Burgt published two new grove-forming leguminous canopy trees, Didelotia and Tessmannia from the Korup forest, together with Gambeya korupensis (Sapotaceae). Van der Burgt also co-authored a paper describing four new species of Englerophytum, while Anna Haigh co-authored a new hemiepiphytic aroid, a Rhaphidophora, from the Bakossi forest.

Remarkable revelations

Perhaps the most amazing and unexpected new species was from the species-diverse Acanthaceae, usually herbs and low shrubs. Iain Darbyshire and Quentin Luke’s Tanzanian Barleria mirabilis (the miraculous Barleria) however, is a tree!

Also from Tanzania, the new Tephrosia (Leguminosae) published by Crawford, Darbyshire & Vollesen and a new Conyza (Compositae) by Henk Beentje. From gypsum outcrops in eastern Ethiopia, Gilbert, Weber and Friis published two new shrubby Commicarpus (Nyctaginaeae); this research, resulting in the discovery of Commicarpus macrothamnus was partly funded by the Carlsberg Foundation - and an image of C. macrothamnus adorns the landing page of their website.

Further discoveries include a new milkwort (Polygala – Polygalaceae) from Zambia co-published by Sara Barrios; two new species of a genus new to Africa, Crossostemma (Celastraceae), from Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique descibed by Iain Darbyshire. Four new Cissus (Vitaceae) were discovered from fossil seeds in Kenya by a team including Felix Forest.

Madagascar: Kew’s top scorer

Finally, Madagascar saw the greatest harvest of new species for 2016. Surely the most wonderful was the new genus Sokinochloa published by Soejatmi Dransfield. These climbing bamboos of forest remnants have spiky ball-like flower clusters: Sokino is Malagasy for hedgehog. Four of the new species were previously totally unknown, and since bamboos often only produce flowers at intervals of ten, or even fifty or more years, much patience was needed over decades to await their appearance, in order to identify and describe the species.

Other new species from Madagascar included a new achlorophyllous mycotroph (‘saprophyte’) Seychellaria barbata, found in shaded forest (Cheek & co-authors), and a flamboyant new Podorungia (Acanthaceae) co-authored by Iain Darbyshire and Guy Eric Onjalalaina. Two new Canephora, members of the coffee family (Rubiaceae) were published by Sally Dawson.

Posthumous discoveries

The vast majority of Kew’s new taxa for 2016 were published posthumously by the late Alan Radcliffe-Smith whose last years of retirement were spent revising the species-rich genus Croton (Euphorbiaceae) for Madagascar. He published 149 new species, subspecies and varieties. Members of this genus of tree and shrub are well-known and appreciated in Madagascar for their medicinal properties. Croton species have three different classes of biochemical compounds with medical applications: diterpernoids, active alkaloids and essential oils.

What is the point of discovering and publishing plant and fungal species new to science?

Until plant and fungal species are given a scientific name, they have no standing in the scientific world. Once a species named, it is also placed into the existing classification which will automatically indicate potential uses and interest, so if a species is described as a new Coffea, researchers will be alerted to a potential new source of coffee. If it is a Croton then it will be of interest to the medical community. More importantly than this, it is only once a species has a scientific name that IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) will accept a conservation assessment for it. Since many species new to science have only just been discovered because they are rare, and therefore vulnerable to threats, assigning them a conservation assessment can be critical to their survival. Developers can refuse to accept an assessment unless it is recognised by IUCN.

Taking responsibility

It is the responsibility of scientists to seek to protect any threatened species that they have helped to discover. We cannot expect locals to protect rare species and their habitat if we do not draw attention to their importance. Our experience in Cameroon has shown that if local communities are given the information on their rare and unique plant species, perhaps through a poster campaign, local pride can be engendered, and locally generated species protection can result, without recourse to national authorities.