9 October 2020

Stuck in time: London’s lichens

Our cities are undergoing a green revolution but are we moving too fast for some species?

It’s the 1960s. You’re standing in a smoggy Trafalgar Square.

Whilst you wait for the number 9 bus to Hyde Park Corner, you notice a rather unhappy-looking oak tree with some crusty white smudges on the bark.

Congratulations observant nature-lover! You have now seen every single lichen species in central London, a grand total of one.

Those unassuming smudges, which on closer inspection look like tiny jam tarts, are the reproductive structures of Lecanora dispersa: the only lichen species left in central London.

What are lichens?

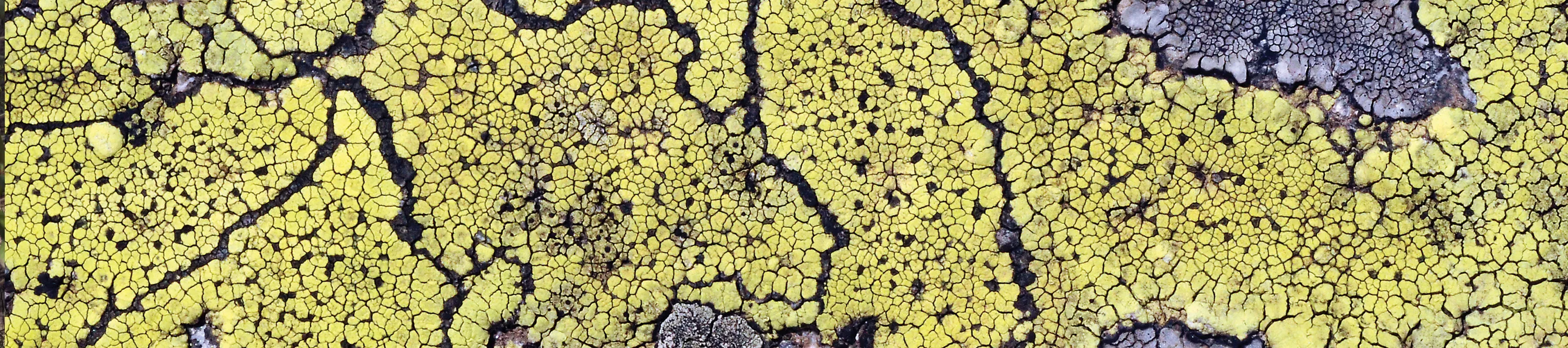

Lichens are symbiotic associations between fungi, algae and potentially numerous other microbes.

They are one of the most diverse and ecologically successful groups of fungi on the planet with around 20,000 currently described species.

They form the base of food webs, fix atmospheric carbon and nitrogen and provide habitats and nesting material for invertebrates, birds and mammals.

Yet despite their ecological importance, lichens are sensitive souls, especially when it comes to air pollution.

Unlike plants, lichens absorb their nutrients directly from the atmosphere and rainwater that runs over them.

This means they also absorb any harmful pollutants that may be in the air and rain.

As London expanded throughout the 19th and 20th centuries and air pollution got worse, lichen diversity dropped drastically from around 130 species to just one.

Fast forward to the 80s

The picture is slightly less bleak.

Crimped hair and shellsuits are in, and Lecanora dispersa is no longer the only lichen species in town.

Restrictions on sulphur pollution resulted in a 50% drop in UK sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions, allowing some of the more sensitive lichens to recolonise the city.

Lichen communities are still low in biodiversity though and are dominated by pollution-tolerant species.

It’s now 2020

As air pollution continues to decrease and London is becoming increasingly green, we should expect lichen communities to be recovering well.

But our new study suggests that they are not.

Urban lichen communities appear to be stuck. Communities in central London parks are restricted to the bark of small trees, they are still dominated by pollution-tolerant species as they were in the 80s, and are nowhere near as diverse as their non-urban counterparts.

What’s going on?

The lichen communities we identified are commonly referred to as pioneers and are normally the first to establish themselves on trees.

These species are fast-growing, hardy and favour the well-lit, smooth bark of young trees.

In non-urban areas, as the tree grows these lichens are slowly replaced by densely packed, highly diverse lichen communities with larger, leafier species.

However, these late-stage lichen communities are highly susceptible to pollution and are often the first to die off in cities.

Also, the large trees on which they prefer to grow were alive during the high pollution climates of the 20th century and may still be carrying this legacy in their bark chemistry.

This makes large urban oaks unsuitable lichen habitats and prevents urban communities from reaching their full potential.

What comes next is unclear

Due to the legacy effects of past sulphur emissions and current nitrogen and particulate pollution it may be many years before the bark of large trees becomes hospitable for lichens and urban communities could remain at a pioneer stage.

This successional stasis limits urban lichen biodiversity, which may also make communities more vulnerable to future perturbations and climate change (a pattern that has already been observed in Italy).

Recovery of London’s lichen communities therefore depends on further decreasing atmospheric pollutants followed by subsequent dispersal events from neighbouring rural communities.

Until this occurs, we can expect trees with suitable sizes for more stable communities to remain devoid of lichens and their high potential microhabitats to remain empty.

References

Llewellyn, T., Gaya, E. & Murrell, D.J. (2020) Are Urban Communities in Successional Stasis? A Case Study on Epiphytic Lichen Communities. Diversity 12, 330.

Lücking, R. Hodkinson, B.P. & Leavitt, S.D. (2017). The 2016 classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota—Approaching one thousand genera. Bryologist, 119, 361–416.

Ellis, C.J. & Ellis, S.C. (2013). Signatures of autogenic epiphyte succession for an aspen chronosequence. J. Veg. Sci. 2013, 24, 688–701.

Giordani, P., Malaspina, P., Benesperi, R., Incerti, G. & Nascimbene, J. (2019). Functional over-redundancy and vulnerability of lichen communities decouple across spatial scales and environmental severity. Sci. Total Environ. 666, 22–30.