13 February 2020

Wallace: The evolution theorist you may not know about

Alfred Russel Wallace deserves recognition like Darwin, thanks to the theory of the Wallace line.

What name do you attach to the theory of evolution?

Is it Charles Darwin?

It’s rare to find for the answer to be another name, one of history’s greatest runner-ups – the name of Alfred Russel Wallace. We are certainly thinking of him at the moment.

But why remember this man now? This year’s orchid festival is inspired by the Indonesian archipelago and the unique cultural and wildlife diversity which Wallace cherished and researched with fascination.

Drawing the Wallace line

At just 31 years old, he travelled around the country for 8 years (1854–1862) collecting animals and plant samples there in collaboration with a veritable army of (mostly) local helpers, guides, and research assistants.

Recent estimates put the number of the staff helping him at one time or another to at least 1,200 people (Wyhe, 2018, p. 41). Together they collected ~125,660 natural history specimens.

It’s here that Wallace came upon a curious pattern.

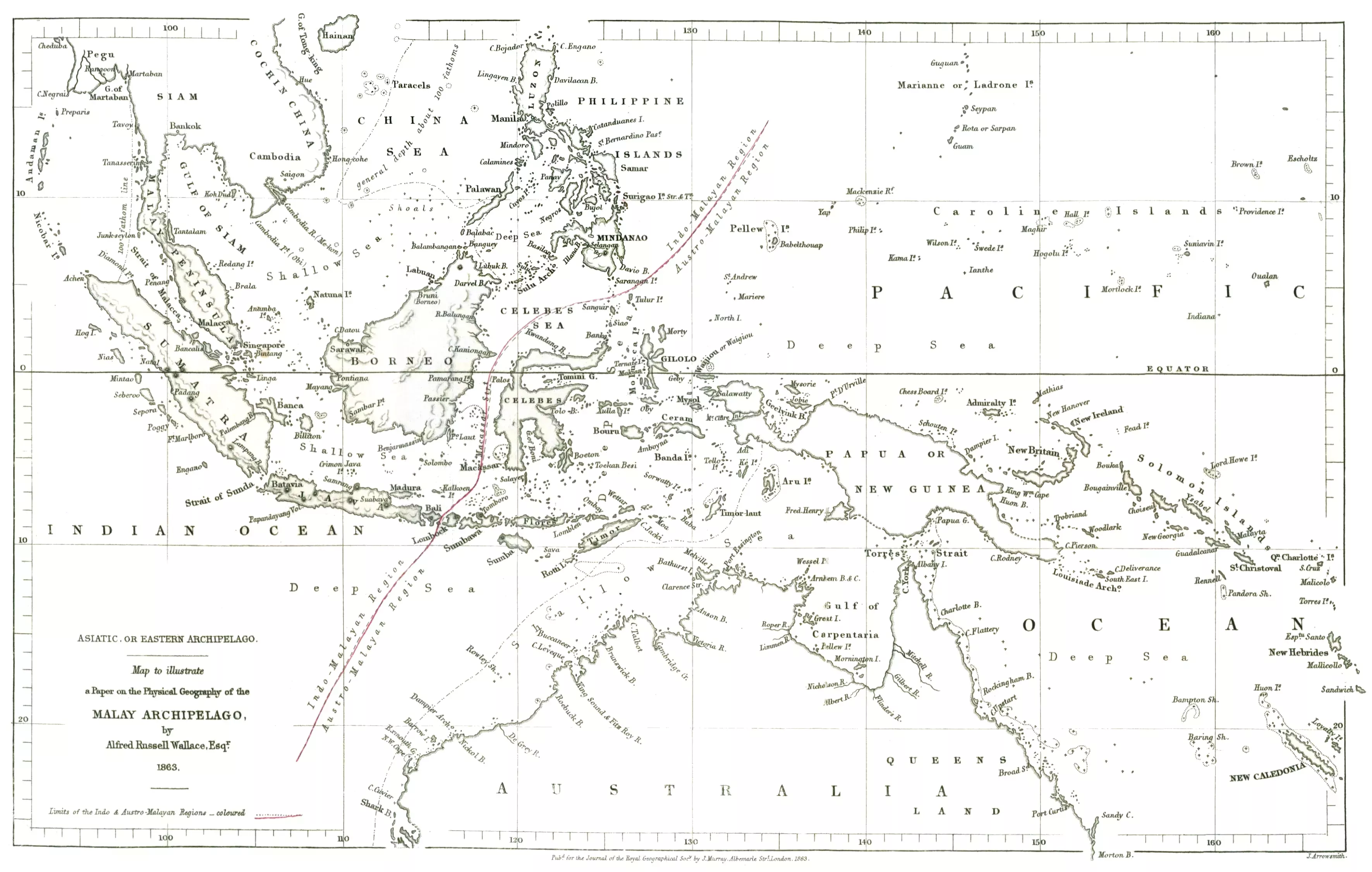

He had travelled for more than 14,000 miles all over the closely-grouped archipelago and noticed that “between these corresponding groups of islands, … , there is the greatest possible contrast in the animal productions.” (Wallace, 1863, p. 232).

He found that islands as close together as Bali and Lombok had completely different animals on them. These two islands are only 22 miles apart – about the distance between York and Leeds – and yet not even birds travel between them.

To account for the phenomenon, Wallace proposed an imaginary line to divide the region into two parts. The animals found on each side of the line can be shown to have an evolutionary connection to either Asia (to the West of the Wallace line) or Australasia (to the East).

Most wildlife on the islands follows this line – even birds and some plants such as certain species of Eucalyptus. This line would prove to be one of the most impactful outcomes of Wallace‘s research in Indonesia.

Wallace, Darwin and evolution

It was whilst immersed in Indonesia’s natural beauty, on the island of Ternate, that he (independently from Darwin) came up with a theory of evolution by natural selection. The idea reportedly came to Wallace in between feverish bouts of malaria.

He immediately penned a paper and sent it off to England where it was read out in 1858 at a fateful meeting of the London Linnean Society together with one of Darwin’s papers suggesting the same theory. Darwin – meanwhile - was so startled by Wallace‘s conclusions that he immediately accelerated work on his masterpiece – On the Origin of Species. It was in print the following year.

Wallace and Kew

Wallace’s most famous publication “The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan and the Bird of Paradise (1869)” opens with a description of the area which includes the fact that the archipelago can (evolutionary speaking) be split in two.

The topic fascinated him and in 1880 he brought out “Island life: or, the phenomena and causes of insular faunas and floras”, which discussed possible reasons for the phenomenon of the Wallace line.

This second book is especially interesting to us because the work was dedicated to Kew’s second director Joseph Hooker. He was one of Wallace’s closest associates and one of the earliest champions of the theory of evolution.”

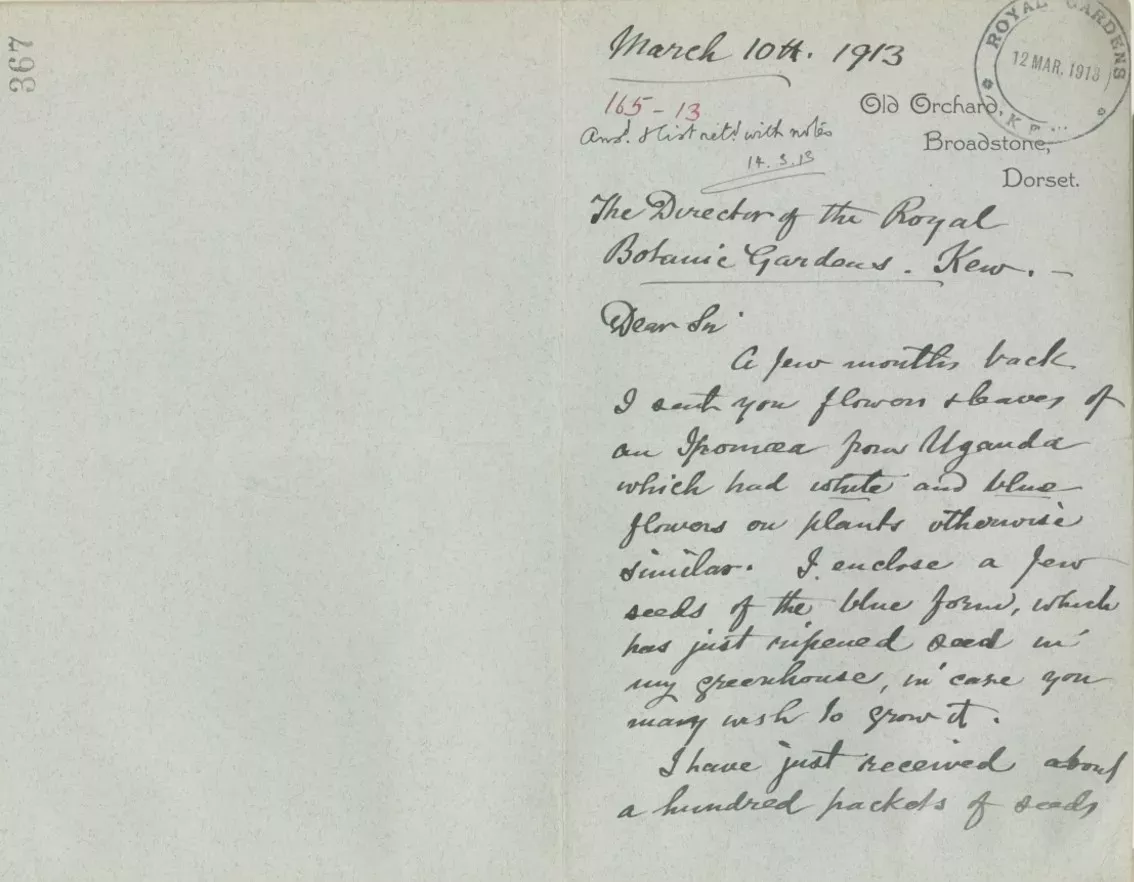

Wallace corresponded with Kew throughout most of his professional life; even when in Indonesia. We can show him to have exchanged letters with four different directors of Kew right up until his death.

This letter (March 1913: the year of Wallace’s death) asked the then fourth director of Kew, David Prain, for gardening advice. His letters that we have show that this was a common topic ; over 135 are in our archive and full transcripts can be found on the Wallace Correspondence Project site.

Science and the Wallace line

To this day, the line affects the work of our scientists in countries like Indonesia. The region has been labelled a biodiversity hotspot and is now known as Wallacea, after Wallace.

The Wallace line itself now forms the Western border of that biodiversity hotspot.

Forests on the islands that lie to the east of the Wallace line within Wallacea are some of the world’s most biodiverse yet little is known about them. Our scientists are working to change that. They are currently working on a project to explore and protect the unique plant diversity that exists within these forests.

If you have been inspired by the orchid festival this year, you can enhance your experience at our library and examine the marvellous art inspired by those plants in our bespoke display.

This article is from our archives and does not fully acknowledge the contributions made by indigenous communities. Kew is committed to telling these stories in a more holistic way going forward.

Sources cited

Wallace, A.R. (1863): On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago in The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 33, pp. 217-234.

Wyhe, John van (2018): Wallace's Help: The Many People Who Aided A. R. Wallace in the Malay Archipelago in Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 91 (314), pp. 41–68.