2 October 2015

The history of tea: From China to India

Read about the history of tea, its journey from China to India and its growth in popularity in England in this second post of a two-part blog by Andrew Butterworth.

The drink for every occasion

You might have heard the phrase "not for all the tea in China", but did you know what the East India Company was willing to do to gain control of the tea trade from its Oriental counterparts? Here we look at the history of tea in more detail.

"If you are cold, tea will warm you; if you are too heated, it will cool you; if you are depressed, it will cheer you; if you are excited, it will calm you." - William E Gladstone (1809–1898), taken from Laura C Martin, Tea: The Drink that changed the World (Tokyo, 2007), p. back cover.

The beginnings of tea in India

In my previous blog post about the Opium Wars, which touched on the history of tea, I explained how the drink became popular in England and how the British failed to renegotiate the payment in silver required. However, that was not the end of the story for tea in China, and only the beginning of the story for India. Even before Joseph Banks (the first unofficial director of Kew) had pressed for a mission to China focussed on tea, he had already considered India. In 1788, he suggested to the East India Company that the climate in certain British-controlled parts of north east India was ideal for tea growing.

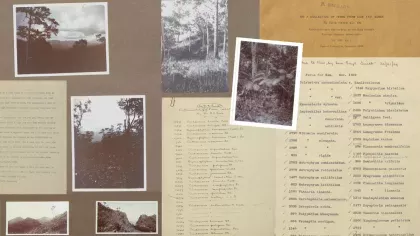

It was a Scottish Major called Robert Bruce who first discovered tea being grown in India. He learnt from a native nobleman, Maniram Datta Barua, that a principal tribe in the Assam state of India called the Singhpho were growing tea. Unfortunately, Robert died in 1824, but he had already sent seeds to his brother Charles to plant in Calcutta Botanical Gardens. Charles Bruce was successful in growing tea there to such an extent that he was even able to send samples of the plants to the Danish botanist Nathaniel Wallich.

"I submit this report on our Assam Tea with much diffidence, on account of the troubles in which this frontier has been unfortunately involved. I have had something more than Tea to occupy my mind, and have consequently not been able to commit all my thoughts to paper at one time; this I hope will account for the rambling manner in which I have treated the subject." - Charles A Bruce, Report on the Manufacture of Tea, and on the Extent and produce of the Tea Plantations in Assam (Calcutta, Aug. 1839), p. 1.

A Christmas discovery

We are perfectly confident that the tea plant which has been brought to light, will be found capable, under proper management, of being cultivated with complete success for commercial purposes." - Nathaniel Wallich on the discovery of the tea shrub that was indigenous to Upper Assam. Laura C Martin, Tea: The Drink that changed the World (Tokyo, 2007), p. 155.

On Christmas Eve 1834, Nathaniel Wallich declared that the samples Charles Bruce had sent were indeed from a tea plant.

Rise of the East India Company

Prior to this in 1833, the East India Company had been seen as becoming too powerful. For this reason, the British government passed the Saint Helena Act which abolished the company’s monopoly over trade in China and the Orient. At that time, China was the only place tea could be imported from, and therefore it was imperative for the company to find an alternative source for what had already become a national favourite in England.

"It (The East India Company) showed little interest in Bruce’s “discovery” of the tea plant (Camellia sinesis var. assamica) growing wild in Assam. Yet in 1834, amid growing tensions with China and less than five months after the Bill to abolish its trading monopoly in China, a government committee was hurriedly set up to investigate the cultivation of tea in Assam." - Peter J Kitson, Forging Romantic China: Sino-British Cultural Exchange 1760–1840 - Cambridge Studies in Romanticism (December 30, 2013), p. 142

A fortunate spy

"Robert Fortune was a Scottish gardener, botanist, plant hunter - and industrial spy. In 1848, the East India Company engaged him to make a clandestine trip into the interior of China - territory forbidden to foreigners - to steal the closely guarded secrets of tea." - Sarah Rose, For all the Tea in China: Espionage, Empire and the Secret Formula for the World’s Favourite Drink (Arrow, 2010), p. back cover.

Today, when we think of espionage, we think of James Bond or Jack Bauer. However, Robert Fortune's successful mission to smuggle tea from China was just as significant as anything these fictional characters have achieved. Travelling through the forbidden city of Soochow (now spelled Suzhou), he wore Chinese clothing and shaved his head, except for a pigtail, to avoid detection. He was the first Westerner to realise that green and black tea comes from the same plants. It is actually the variations in processing the tea which lead to the different outputs — green tea is un-oxidized while black tea is produced by oxidizing the leaves. Using Wardian cases (glass-sided, airtight cases for transporting live plants), he managed to send 20,000 tea plants on four different ships to avoid the possibility of catastrophe.

Although Fortune’s trip was successful, Assam soon proved to be a far more significant tea source. By 1890, India supplied 90 percent of Britain’s domestic market. India paid a large price for this. Many ‘coolies’ and elephants died when large forest areas were cleared to make space for plantations. What's more, India was only allowed to keep 15 percent of plantation profits. Maniram Datta Barua, who had first told Robert Bruce of the tea in the region, participated in the 1857 uprising against the British, and was subsequently hung for his actions.

Clipper competition

After the East India Company lost its monopoly in 1834, it sold its “tea wagons", large solid ships that could be described as, literally, “slow boats to China”. The demise of the East India Company - along with the introduction of the Navigation Acts, which meant anyone, including non-English companies, could bring goods into a British port - led to there finally being competition on imports. Clipper ships became “the new force in the highly profitable merchant trade”.

However, the development of steamships in the early part of the 1800s, and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, sadly brought about an end to clippers. The last surviving tea clipper, the British Cutty Sark, was fully restored and reopened in 2012 at its dry dock in Greenwich.

- Andrew Butterworth -

Library Graduate Trainee

Further reading

Charles A Bruce, Report on the Manufacture of Tea, and on the extent and produce of the Tea Plantations in Assam (Calcutta, Bishop's College Press, 1839)

Emil Bretschneider (1833–1901), History of European botanical discoveries in China (London : Sampson Low, Marston and Co, 1898)

China. Hai guan zong shui wu si shu, [Opium in China] (Shanghai : Statistical Deptartment of the Inspectorate General, 1881–1888)

Samuel S Mander, Our Opium Trade with China (London, 1877), MR/91 — China - Foods, Medicines and Woods 1869–1914 — Kew Archive

Laura C Martin, Tea: The Drink that changed the World (Tokyo, 2007)

John Elma Rahn, Plants that changed History (New York, 1985)

Sarah Rose, For all the Tea in China: Espionage, Empire and the Secret Formula for the World’s Favourite Drink (Arrow, 2010)

Nicholas J. Saunders, The Poppy: A Cultural History from Ancient Egypt to Flanders Fields to Afghanistan (London, 2013)

Sir George Staunton (1781–1859), An authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China (London : G. Nicol, 1798)