8 September 2017

Richard Spruce: botany on a global scale

We explore the career of one of the most extraordinary and modest of Victorian naturalists, Richard Spruce, as part of celebrations to mark the bicentenary of his birth.

“I like to look on plants as sentient beings…"

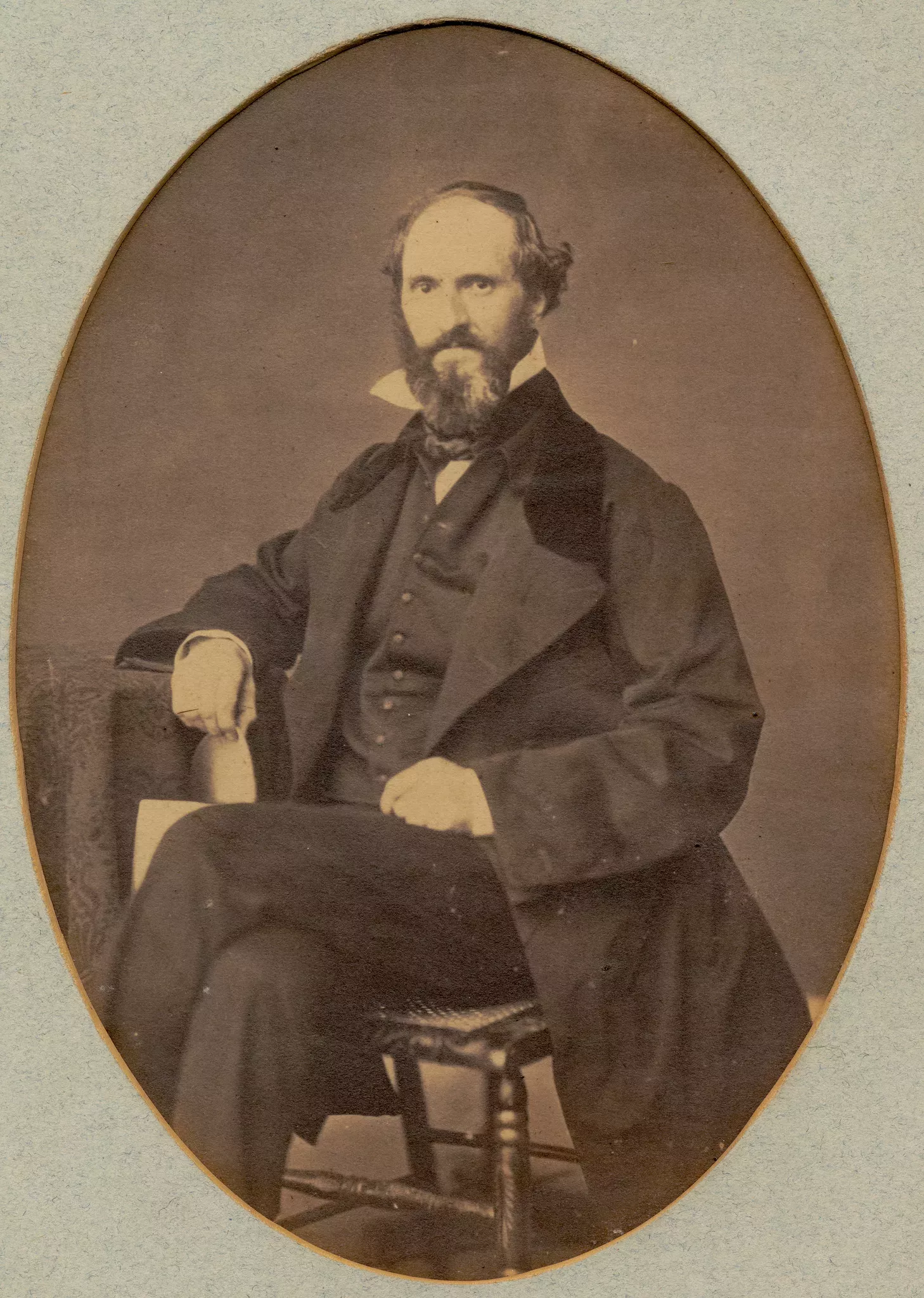

Born in Yorkshire in 1817, Spruce developed a love and scholarly appreciation of the plants of his local neighbourhood at an early age and was particularly fascinated by the liverworts (hepaticae) and mosses.

“I like to look on plants as sentient beings… which live and enjoy their lives — which beautify the earth during life, and after death may adorn my herbarium… It is true that the Hepaticae have hardly as yet yielded any substance to man capable of stupefying him, or of forcing his stomach to empty its contents, nor are they good for food; but if man cannot torture them to his uses or abuse, they are infinitely useful where God has placed them, as I hope to live to show; and they are, at the least, useful to, and beautiful in, themselves — surely the primary motive for every individual existence”

(Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes, 1908)

With no family connections or inherited wealth, Spruce brought himself to the attention of botanists and plant collectors through his thoughtful publications in journals such as The Phytologist. Following a successful plant collecting expedition in the Pyrenees, Spruce left England in December 1849 to collect plants in South America, remaining abroad for 15 years and travelling through Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela.

To the Amazon and Andes

Despite the difficulties of exploring and collecting in remote locations, constant exposure to tropical elements and even at one point a murder attempt, Spruce made wonderfully detailed plant collections and records. Meanwhile in England, the botanist George Bentham was busy receiving, naming and distributing the thousands of plants Spruce obtained amongst a series of paying subscribers.

During his travels, Spruce would encounter two other giants of the Amazon - the lepidopterist Henry Walter Bates and the zoologist Alfred Russell Wallace, with whom he exchanged information and advice.

Spruce recorded plant uses as he travelled, including gums, resins, drugs, narcotics, stimulants, foods, fibres, oil, dyes and timbers; trying to botanically determine their sources. He provided science with some of the first extensive botanical knowledge of Hevea rubber. Furthermore, he recorded the customs and traditions of the different communities he met, making him an early ethnographer in the Amazon and Andes.

Cinchona and the fight against malaria

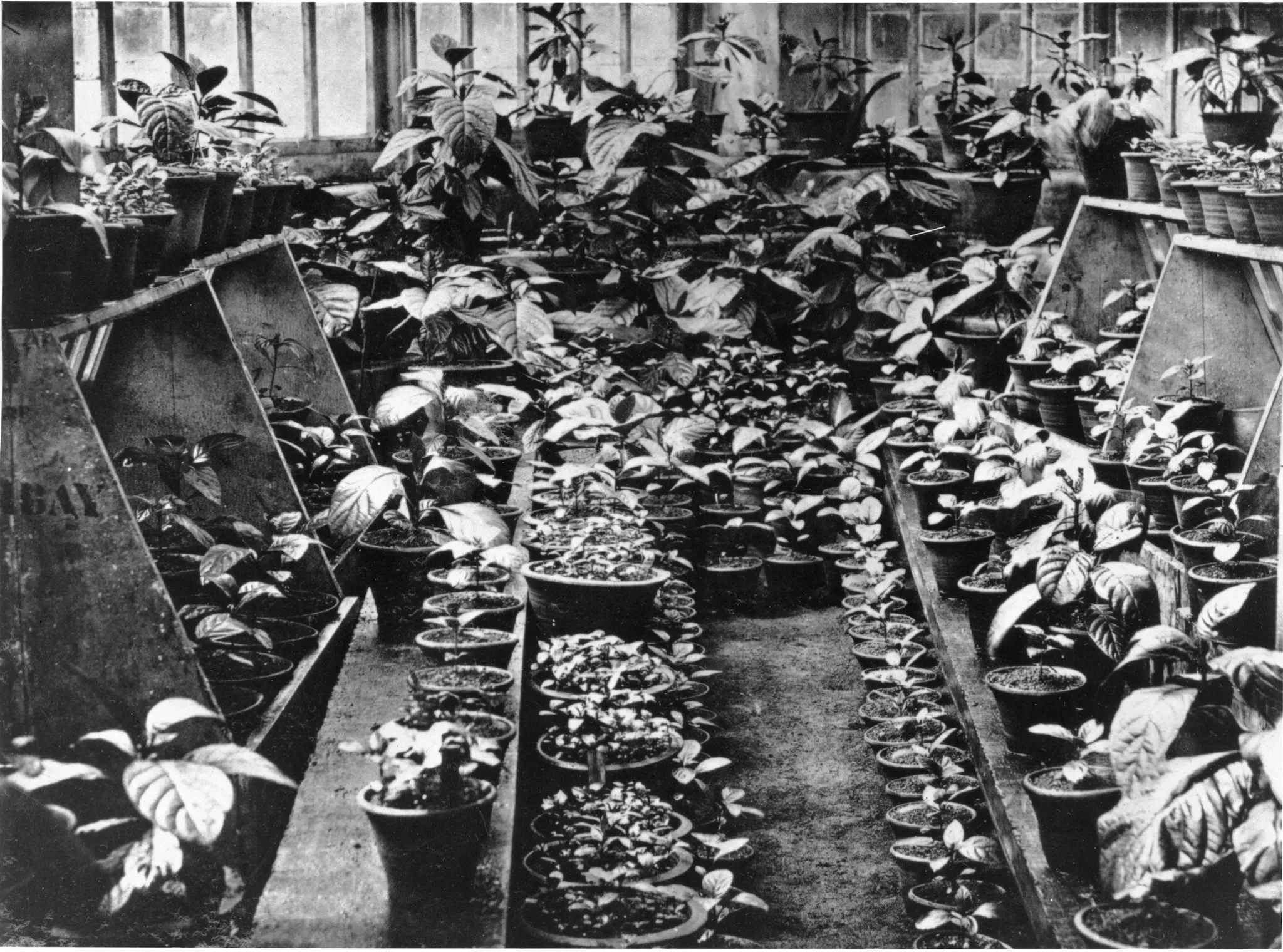

In 1859, Spruce was commissioned by the British Government’s India Office to collect seeds and young plants of the “red bark” Cinchona, the source of quinine, to ship to the East, where it was planned to grow them in plantations on a major scale. Quinine derived from the bark of the red Cinchona was already highly valued as a medicine to combat fever and was starting to be recognized as crucial in the control of malaria. Supplies of the bark were expensive and becoming harder to obtain as the basic method of harvesting had been to cut down the tree and strip it, with no thought of replacement. Despite poor health, Spruce supervised the collecting of 100,000 seeds and 600 plants on the western slopes of Chimborazo in Andean Ecuador. Spruce’s investigations into the various types of “red bark” became the foundation of plantations in India and Ceylon which brought relief to thousands of malaria sufferers.

Following his return from South America in 1864, Spruce spent the rest of his life in Yorkshire working up his collections and writing his magnum opus The Hepaticae of the Amazon and the Andes of Peru and Ecuador. Now over 130 years old, this work is still the most important reference on tropical South America hepatics.

After his death, Spruce’s travel notebooks were edited by Wallace and published in 1908 as Notes of a botanist on the Amazon & Andes, bringing his gift for narrative, analysis and dry humour to a wider audience. Spruce is also commemorated in the names of many plants including the moss Sprucella, the liverwort Sprucea, and several orchid species.

In his bicentennial year, Spruce’s legacy is very much alive and well and in collaboration with Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden, Instituto Socioambiental, Birkbeck-University of London, and the Goeldi Museum, Kew has been using Spruce’s collections and observations in their communities of origin to stimulate new research and perspectives on the relationship between people and plants in the Amazon.

Spruce’s collections are also inspiring new artworks with a forthcoming exhibition in the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art, ‘Lindsay Sekulowicz: Plantae Amazonicae’ (7 October 2017 - 11 March 2018). Following collaborative work with Kew’s Science team, Lindsay has produced a series of pieces illuminating Kew’s Amazon rainforest collections, focusing on Spruce’s ethnobotanical collections. These collections, ranging from poison arrows to barkcloth clothing, have enabled Lindsay to explore the relationships between people and the natural world, a sentiment Spruce would surely be strongly in agreement with.

- Kat Harrington –

Assistant Archivist