3 August 2023

The future of plant conservation in Mozambique

Across six years, our knowledge of Mozambique’s flora has blossomed. Now it’s time to decide how to protect it.

Mozambique is one of the most nature-diverse nations in tropical Africa. Incredible variation in ecosystems and species can be found here. What unites it all is that until recently, it was some of the least scientifically studied biodiversity around.

This absence of knowledge is the greatest challenge for conservationists and policy makers. Which areas hold the highest value for conservation investment? How do you combine wildlife needs and human needs if part of the picture isn’t complete?

Research Leader for Accelerated Taxonomy (Africa), Dr Iain Darbyshire, was one of the founding scientists behind Kew’s Tropical Important Plant Areas (TIPAs) – an initiative that seeks to answer these fundamental challenges. If we can identify the most critical spots of life, can we champion their protection?

Mozambique TIPAs begins

Since it began in 2017, the six long years of the Mozambique TIPAs project have seen a botanical boom. Plant surveys have united researchers from Kew, Mozambican universities and government authorities (in particular the Agricultural Research Institute of Mozambique and Eduardo Mondlane University).

Already by 2019, the first ever list of Mozambique’s endemic plants had been crafted. These are the plants found nowhere else in the world other than within Mozambique’s borders.

From this list, extinction risk assessments were made for 373 Mozambican plant species for the first time.

Plenty of species are thriving, and we hope to keep things that way. Many high montane grasslands, for example, are rich in endemic species and remain largely intact across the country.

On the other hand, 53% of the endemic and near-endemic species assessed are considered “threatened”, many in some state of decline or restricted to a tiny range.

Ncuri – or icuri (Icuria dunensis) – is one, a spectacular coastal forest-forming tree of the legume family, found exclusively in northern Mozambique. It is Endangered because of threats from habitat degradation, mining of mineral-rich coastal sands and over-harvesting of its wood and bark.

Focusing all our attention on individual species won’t save our planet’s wildlife however, we need to take it to a higher level.

Landscape-level conservation

In 2017, a fledgling Mozambique TIPAs project sought to identify a list of potential wildlife hotspots for investigation. From coastline to dry forest, to the mountain peaks beyond the clouds, it’s a lot to examine.

To be classified as a TIPA, a site must contain at least one of three things, and the more the better.

Threatened species – particularly endemics and species threatened at the global level

Botanical richness – assemblages of species that are important in terms of ecology and conservation, but also species that are significant socially, i.e. culturally and economically important plants

- Threatened habitats – especially habitats in decline, and those rare beyond Mozambique

We asked Iain to walk us through the process of understanding a TIPAs landscape:

“Take the Chimanimani mountains for example. A 319 km2 national park extending across Mozambique’s western border into Zimbabwe. Some of its smaller hills hit 1200m above sea level, already rivalling the highest UK mountain peaks. The largest are more than two and half kilometres into the clouds.

“Walking through this landscape you might not expect it to be so extraordinarily rich with life – you really have to get down and look at the detail.

“The most interesting areas are the quartzite crags, ledges and even individual boulders that each support unique rock-growing plant communities. The environment is so harsh and nutrient levels so low that plants must specialise to cope, and where you see specialisation, you see diversity.

“With a huge collection of endemics, at least eight endangered species making their home here, and an assortment of habitat types, it’s most certainly a globally important site for biodiversity and in fact, the most botanically rich site in Mozambique."

Detail beyond wildlife

“The key fact of Chimanimani, however, is that it’s already a National Park, and one that’s relatively uninhabited by people. Smallholder farming, goldmining and the potential development of tourism are things to keep an eye on, but this is among the more secure biodiversity sites surveyed.

“On the other end of the spectrum is the coastal region of Bilene-Calanga. Here the blue seas and waving Raphia australis palms are the sight to see. There are more palms of this species in the wetlands here than anywhere else on Earth. The coastal forests here host every known individual of a small shrub species, Memecylon incisolubum, and many other species facing issues beyond the region. The pressure of deforestation here is massive, and so far, near to no protection is gifted to the area.

“Most notably, the Chihacho forest that hosts M. incisolubum has survived so far because it is sacred to the communities who call this region home. The edges are gradually being chipped away however, and so a sustainable management plan will be the key to its future.

“Mozambique’s TIPAs bring challenges as diverse as the wildlife found in them, but now we have a targeted way to approach each.”

Protecting a lot with a little

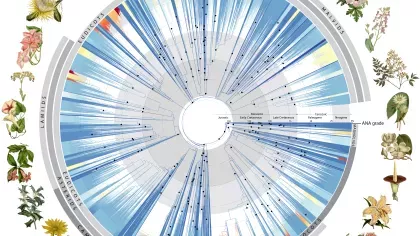

Here in 2023 we’re celebrating a massive achievement – a network of 57 TIPAs sites containing 22,950 km2 of some of the most botanically valuable land on Earth.

This sounds like a lot, but it is in reality only 3% of Mozambique’s land area. It contains important populations of over 80% of all known threatened species in Mozambique, and 75% of Mozambican endemics and near-endemics. You can protect a lot with very little.

At the time of writing, only 18 of 57 TIPAs sites are currently safeguarded by the Mozambique Protected Area network. With nearly 30% of its total terrestrial area given some level of protection, Mozambique is already very generous with its wildlife protection in line with its commitments under the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, but the addition of the relatively small extra areas identified under the TIPAs project would make a world of difference to the protection of its unique plant diversity.

TIPAs support governments to make scientifically-supported decisions that get the very best value out of protected areas, and help provide the solutions to complex problems.

The bigger picture

In just over half a decade, the Mozambique TIPAs initiative has revolutionised the botanical study of a nation. It has also trained a generation of botanists that will be at the forefront of establishing Mozambique’s next conservation initiatives.

For Kew, our commitment to Mozambique does not end here. Our seed-banking programme under the Millennium Seed Bank partnership will focus on the sites and species highlighted through TIPAs, and in time, hand-in-hand with in-country partners, we hope to see community-led initiatives grow.

The single largest (physical) output is undoubtedly the Mozambique TIPAS book, the details of all 57 sites in all their fully-illustrated glory across 427 pages – a collaborative triumph. Alongside the English version, a Portuguese edition will arrive in late 2023, as part of an official release in the Mozambican capital, Maputo.

In the wake of a new global biodiversity framework, the world is re-assessing the road ahead, and prioritisation projects like TIPAs are the means to craft quick and well-planned conservation actions – something we’re in need of to restore our natural world in time.

We are grateful to The Jonathan and Jennifer Oppenheimer Foundation and Stephen Lansdown CBE and Margaret Lansdown for their generous support of the TIPAs Mozambique project.