1 July 2014

The medicinal plant names maze and why it matters to us all

How the work of our Medicinal Plant Names Services (MPNS) enables safer and more effective communication by those using medicinal plants.

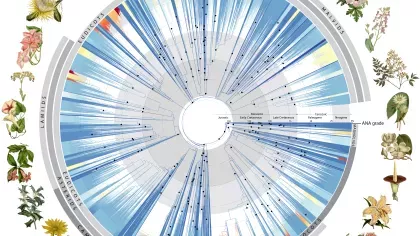

Kew is at the forefront of plant name research and hosts the world’s major names and taxonomy databases: The International Plant Names Index, World Checklist of Selected Plant Families and The Plant List.

These databases collate information about all the scientific names that have been published for plants, and present the current consensus on which are the accepted names that should be used and which are synonyms (alternative names for the same species, subspecies, variety or forma).

There are approximately 1.6 million published plant names but only an estimated 350,000 plant species, so the potential for confusion is clear. However, for anyone conducting scientific research on plants, involved in regulating illegal plant trade, or working in any of the many industries that use plants and their products, it is important to know which names relate to which species and which is the current accepted name. This is all the more important for medicinal plants, where the consequences of confusing different species can be very serious.

The major names and taxonomy databases are aimed primarily at a scientific audience, and only deal with the scientific names of plants. In the wider world, however, plants are known by a range of other names, such as common, trade and pharmaceutical names. It is these names that people use when talking to each other or even when prescribing medicinal plants or reporting suspected poisoning from plant material. And yet, unlike scientific names, there are no rules to govern which name is used for each plant. Because medicinal plants cross regional and national borders and herbal traditions, they are known by a number of different names. In addition, a single name can be used for more than one plant. Using the wrong plant in a herbal preparation has important social and economic consequences: manufacturers have to make costly product recalls, and individuals can suffer adverse health effects and even death.

This was highlighted in the early 1990s when a Belgian slimming clinic used the wrong plant in its regimen. Instead of prescribing the root of Stephania tetrandra S.Moore, a plant used in Traditional Chinese Medicine and known by the pin yin name ‘han fang ji’, they used ‘guang fang ji’. Unfortunately, guang fang ji is the plant Aristolochia fangchi Y.C.Wu ex L.D.Chow & S.M.Hwang which contains a group of chemicals called aristolochic acids. Taken over a long period, aristolochic acids are toxic to your kidneys. At least 105 people suffered from renal failure as a consequence of confusion between these different types of fang ji.

The Plant Name Services programme aims to increase accessibility to Kew’s plant name data. It has begun with a flagship initiative to meet the needs of people working with and using medicinal plants, which are among the most widely used and economically important plants. Supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust, Medicinal Plant Names Services (MPNS) is compiling a unique information resource. This builds upon Kew’s existing taxonomic resources and enriches these with plant names as they are actually used within legislation and the medicinal plant literature, for example, national pharmacopoeias. This resource thus connects the most up-to-date scientific name for a species (and its known botanical synonyms) to both the scientific and non-scientific names used in the medicinal literature, including where those names may be misspelled or misused.

The MPNS resource currently covers approximately 13,000 species, corresponding to 20,600 scientific names used in the literature. It links these to 30,000 non-scientific names from the same literature, and to over 100,000 scientific names (synonyms) in Kew’s taxonomic databases. The inclusion of non-scientific names (trade, pharmaceutical and common names in many languages) makes Kew’s taxonomic information more accessible and relevant to a wider audience.

To help us understand the requirements of our users, their priorities and the benefits they achieve by using our services, MPNS has formed a User Group. We held two workshops with representatives from leading organisations in medicinal plant regulation, research and practice. During the workshops delegates tested a pre-release version of the MPNS portal, which provides online access to the MPNS resource. The workshops also sought the views of stakeholders on our other services, such as name validation and consultancies, which MPNS provides to organisations managing information on medicinal plants. We were extremely pleased with the enthusiasm of the participants and overall feedback on the coverage of the resource and service priorities.