2 November 2018

Kew Gardens in the First World War

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew was much more than a beautiful green space during the First World War. Here are the many and unexpected ways the Gardens and staff made a big impact on the war effort.

Remembrance and hope

Exactly a century after the end of the First World War, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is unveiling its ‘Remembrance and Hope’ seat, encouraging visitors to reflect on Kew's wartime era.

The specially designed bench, made from the Gardens’ fallen Verdun oak tree which grew from an acorn salvaged from the battlefield of Verdun, France, in 1917, honours the lives lost at the battle but also the 37 Kewites (19 members of staff at the time) who died during the First World War.

During this period of terrible conflict, Kew adopted many roles to assist the war effort, some of which are little known and surprising. Here is Kew’s story during the First World War.

Garden therapy

Despite the ongoing war from 1914 to 1918, Kew remained open to the public.

Populated with stunning trees, green lawns and wonderful flowers, the Gardens became a much-needed haven for those seeking solace.

Kew provided the chance to reconnect with nature and a tranquil setting for recovering soldiers to gain a positive stimulus through ‘garden therapy’.

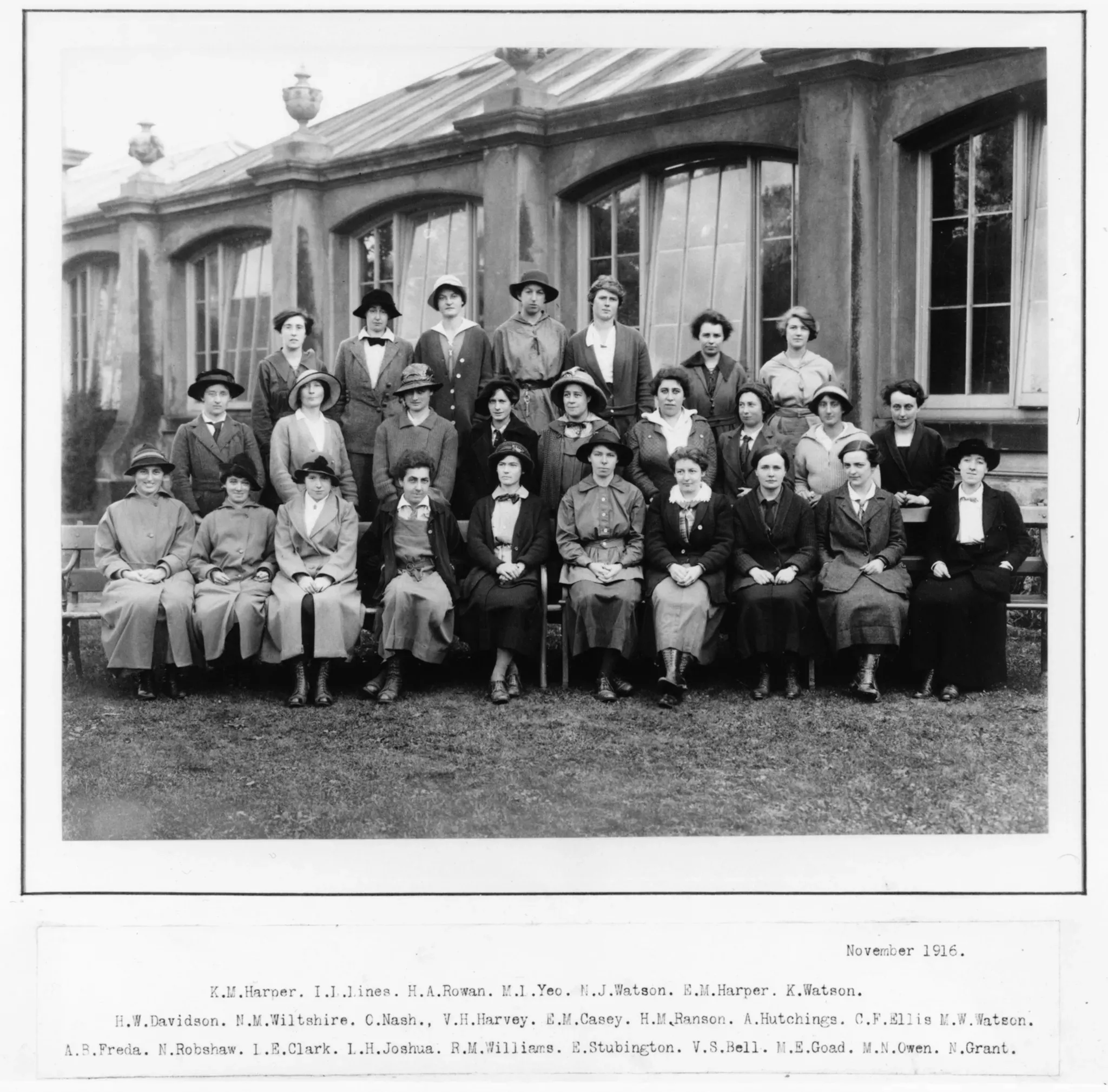

Women join Kew’s forces

Like most young men, those at Kew enlisted to serve their country – 124 went to war to serve in all different ranks, from scientists to gardeners.

The Gardens’ staff force was notably reduced. So, for the first time, women were employed at Kew in significant numbers from 1915 to cover the roles of men who had left for war.

Initially set to work on the Herbaceous Grounds, Rock Gardens and Flower Gardens, women began taking on other roles as more men left to fight, including in the glasshouses and as assistants in the Herbarium.

In 1915, 24 out of 38 regular gardeners were women. By 1918 there were 27 women gardeners here at Kew.

Even though many of the new female workers were trained at horticultural colleges, their appointment was met with some negativity by those who didn't think women were up to the job.

It became clear, however, that the women gardeners were a valuable asset to Kew after proving their intelligence, diligence and capability.

After the war ended though, things returned to the way they were before and by March 1922 there were no female horticulturists working here. This was set to change again at the outbreak of the Second World War.

Read more on Kew's women gardeners during the First World War.

Wartime research

As well as the benefits of the visitor facing Gardens, secret war work was taking place behind the scenes at Kew.

Our botanists used their unique expertise to invest in research on wartime matters, some of which had an unlikely connection to our world-class scientific institution.

James Wearn, Kew’s resident war expert and ecologist, wrote in Kew magazine, ‘Senior scientists who were too old for military service and those in reserved occupations became engaged in war work, which, although using their core skills, was often quite different from their normal lines of research.’

Several organisations and government departments came to Kew for botanical help on a range of topics.

These included looking for alternatives to medicinal plants that could no longer be imported, food crops, plant material identification, aircraft research and even finding alternatives for building fake shrubbery for theatres.

‘Numerous queries and samples were sent to Kew during the world wars by the Ministry of Munitions (especially the Munitions Inventions Department), the Aeronautical Inspection Department and small arms factories, for example to ascertain from what strange materials opposition aircraft were being made,’ James Wearn added.

Much of the research took place in Kew’s old Jodrell Laboratory and many of the items sent to us for examination are now kept in Kew’s Economic Botany Collection, which can be visited by appointment.

Find out about other sites at Kew that hold First World War significance.

Food production

One major problem for people at home during the First World War was a shortage of food.

To help ease the situation, parts of Kew Gardens were transformed – the Palm House parterre and Kew Palace lawn were dug up to grow vegetables for the Home Front, from onions to potatoes.

The lawn alone produced 27 tonnes of potatoes as a great contribution to the war effort.

War graves

Kew’s assistant director at the time of the First World War was Sir Arthur Hill (later Kew's director) who became a prominent figure in memorialising those who lost their lives.

Hill became the official ‘botanical advisor’ to the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC), a British institution set up in 1917 to mark, record and maintain the graves and memorials of the First World War dead – formerly known as the Graves Registration Commission.

The role involved Hill visiting war cemetery sites in France to offer advice on landscaping and planting, along with horticultural officers, several of whom were Kew staff.

The IWGC was renamed Commonwealth War Graves Commission in 1960 and now looks after cemeteries and memorials of both world wars.