15 October 2021

How did Japanese plants get into British gardens?

From botanical smugglers to coded telegrams, Library Graduate Trainee Cecily Nowell-Smith reveals how plants from 6000 miles away made it to our gardens.

The Gardens at Kew are rich with plants that originated in Japan, from delightful white and pink blossom among the trees in our Cherry Tree Walk, to subtle shades of foliage in our Japanese Landscape.

It doesn’t stop there; gardens across the UK are full of hostas, azaleas and hydrangeas that were first cultivated 6000 miles away in Japan.

Our gardening would be incomparably poorer without foreign plants introduced by generations of visitors, migrants, merchants, governmental bodies — and even the plants themselves hitching a ride on some other cargo.

Writing in the Journal of Horticulture and Cottage Gardener in 1878, Edward Luckhurst was delighted by the number of Japanese plants available to the domestic gardener.

Suggesting gardens showcase only Japanese flora, Edward wrote “That such a garden would be attractive there can be no doubt, … for everything brought from that country has peculiar points of beauty whether in habit of growth, form, or colour of foliage or blossom.”

But how did those plants get to the UK in the first place?

Smuggling

In the early seventeenth century, the Japanese government were highly suspicious of foreign merchants and missionaries.

They established tight control of all trade and contact with the outside world.

In order to lessen their dependence on trade, they even learned to produce their own sugar in the eighteenth century, using books and information from China.

The Japanese authorities chose the Dutch as their only Western trading partner.

Dutch merchants were restricted to a small artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki, called Dejima, and forbidden to travel or have visitors without specific approval.

Even so, curious members of the delegation tried to learn all they could about the country, including investigating the local flora.

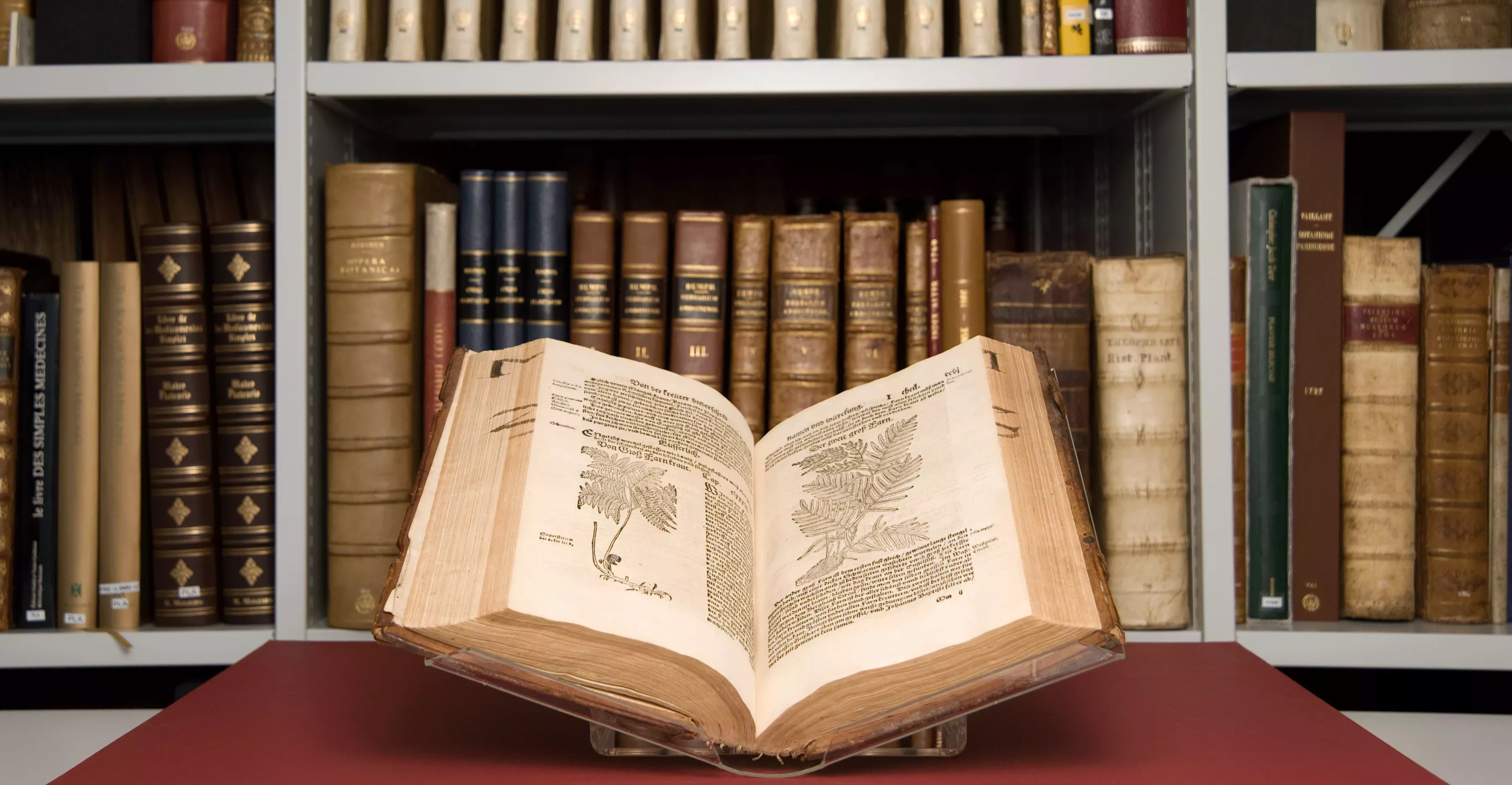

Avid naturalists such as Carl Peter Thunberg (1743 — 1828) and Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796 — 1866) made detailed botanical observations and went so far as to smuggle plants for their own nurseries.

This curiosity was not without consequences. When it was discovered in 1828 that von Siebold had been trading Western books for maps of Japan, he and his Japanese correspondents were put on trial.

One of the correspondents died in prison and von Siebold himself was expelled from the country.

Plant hunting

A series of offshore encounters, and finally the arrival of an American gunboat, forced Japan to open to the outside world in the 1850s.

This world was dominated by large Western powers on the lookout for new international trade opportunities.

Europeans and Americans really wanted to find out what was unique in Japan — they sent all kinds of things home to study and sell, sparking a fashion for Japanese objects and art.

One of Kew’s Herbarium assistants, Charles Wilford, arrived in Japan in 1859 on a specimen-collecting tour that also took place in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea.

Charles was followed in 1860 by the famous plant-hunting botanist Robert Fortune, who used the new technology of Wardian cases to send home living specimens.

John Gould Veitch, of the successful Veitch nurseries, arrived at the same time.

The Veitch nurseries were renowned for importing and cultivating exotic plants and were looking for more exciting things to sell.

Among the first flowers John sent back to the UK in bulb form was the Japanese golden lily (Lilium auratum). This was grown straight away and displayed to great acclaim in the Royal Horticultural Show in Chelsea in 1862.

Plant hunters or thieves?

For the first Western ‘plant hunters’, finding new and beautiful plants in Japan was a remarkably easy job.

They could just buy them from Japan’s commercial nurseries, which had been supplying domestic customers with magnificent, cultivated plants for centuries.

Those looking for wilder plants needed official permission.

Japanese authorities, eager for the country to be recognised as a modern nation like the Western powers, were willing to welcome them.

Even von Siebold, despite his previous banishment, was allowed to return.

Japan also asserted itself like a Western power by amassing its own colonial empire.

Western plant hunters treated places like Formosa (modern Taiwan) as belonging to Japan: they saw the indigenous inhabitants as colonial subjects, not as experts in or custodians of their own land.

Buying by mail order

Nursery businesses based in the UK, like Veitch or Gauntlett’s Japanese nurseries, grew Japanese plants for sale in the UK from the late 1800s. But plants could also be bought directly from Japan.

Louis Boehmer, an American agronomist employed by the Japanese government, set up a nursery business in Yokohama in 1882, selling to the European and American markets.

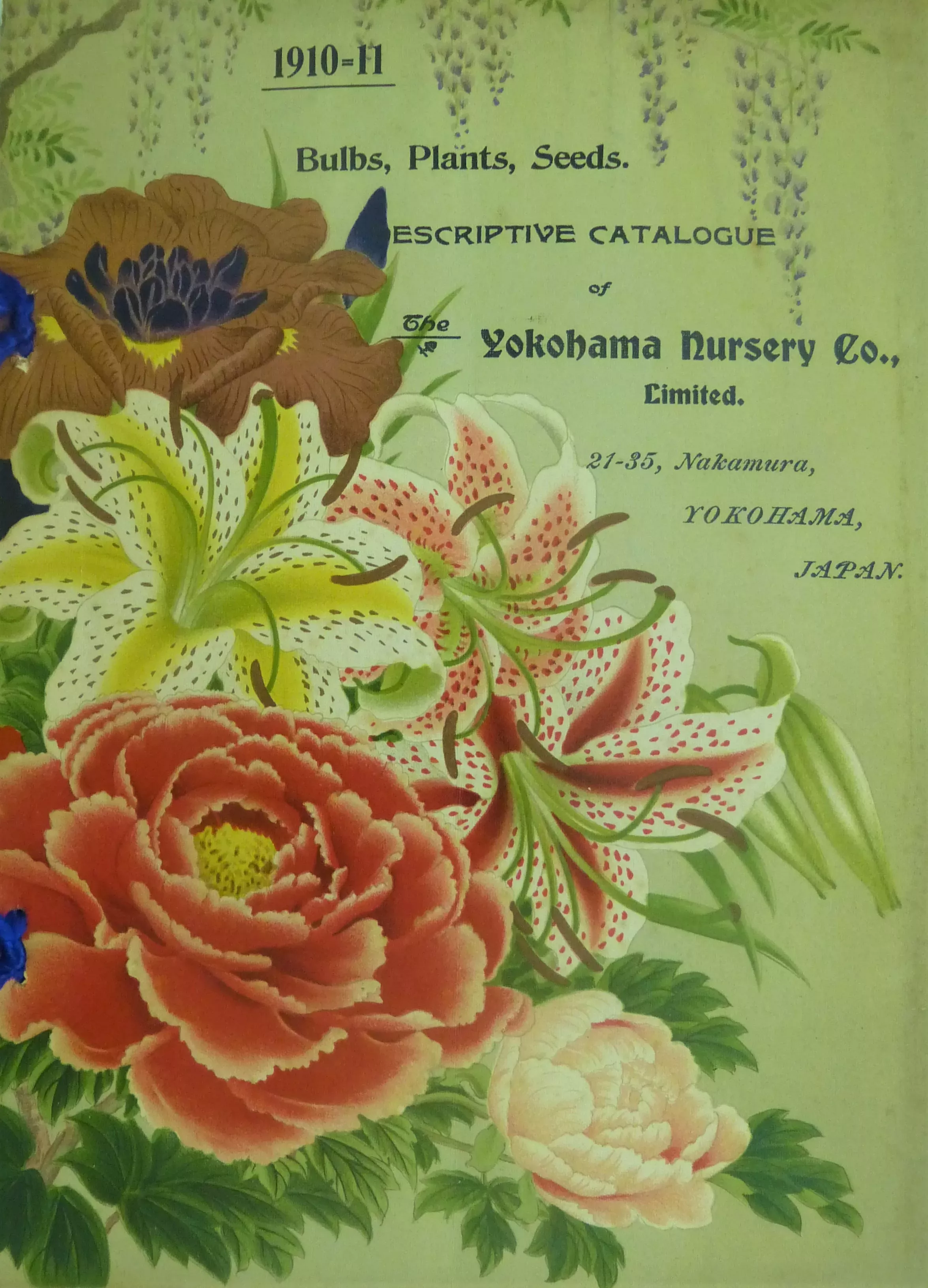

In 1891, a group of Japanese nurserymen led by Uhei Suzuki set up a rival business, the Yokohama Nursery Company, which still operates today.

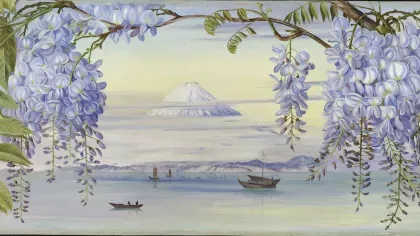

Kew’s library has some of the nursery catalogues sent out by the Yokohama Nursery Company.

Not only are they beautiful, they also tell us a lot about how people were able to get plants all the way from Japan.

People could buy plants in pots, bulbs and seeds, and fern balls for house decoration, as well as porcelain flower pots, garden statuary, and bamboo poles.

Plants were sent by steamship, which took about two months to get from Yokohama to London.

Orders could be made by sending a coded telegram. The code was not used for secrecy, but rather it made the message more concise and understandable.

Making a British Japanese garden

The Yokohama Nursery Company were a wholesale supplier to the Veitch Nurseries and provided a large number of plants for the two gardens at the Japan-British Exhibition of 1910.

This was the first opportunity for many British gardeners to see what Japanese plants might look like in a Japanese garden.

People could also learn more from an increasing range of paintings, lithographs, and books about Japanese plants and garden design.

The garden plans in Josiah Conder’s 1893 classic Landscape Gardening in Japan, available in the Yokohama catalogues, were used as a direct reference for a number of British 'Japanese' gardens.

Few people could afford to build a Japanese garden of great size or make gardens to Japanese standards of authenticity.

Even after Japanese garden designers started to work in Britain, their gardens ended up being hybrids of Japanese and British aesthetics, and the fashion for Japanese-style gardens faded after the 1920s.

Japanese plants, though, became entirely naturalised members of the British garden: look out for the Japanese cherry trees, azaleas, bamboos, chrysanthemums, miniature maples, and more next time you visit Kew.