What's in a collection? The Herbarium at Kew

William Milliken, Head of Kew's Tropical America team, examines the importance of Kew's collection of over seven million herbarium specimens, and how this resource is being used to tackle the global challenges of our time.

The initial reaction of most visitors to the Herbarium at Kew is an audible gasp. The transition from the modern foyer into the extraordinary Victorian three-storey ‘vault’ known as Wing C, with its elaborate ox-blood ironwork, spiral staircases, floor-to-ceiling wooden cupboards, boxes and bundles of specimens wrapped in newspaper from the four corners of the globe, and the elusive odour of innumerable exotic dried plants, gives the sensation of walking back in time.

It would be no great surprise to find Darwin bent over a microscope in one of the many window bays, quietly poring over a rare South American sedge.

Innumerable is about right, we’re still not exactly sure how many herbarium specimens are held at Kew. It’s somewhere in the region of seven million, with about thirty thousand new additions every year. Roughly every thirty years since its original construction in the 1870s, another wing has had to be built to house this expanding library of the world’s plant diversity. The latest is a state-of-the-art affair with temperature-controlled vaults and compactor shelving, designed for optimum storage conditions and minimum risk of pest damage.

Maintaining this collection in good order is a huge and expensive task. This needs to be justified. Natural history collections were all the rage in the 19th century, when documenting and describing the natural world was seen as a justifiable end in itself. Nowadays, institutions such as Kew are expected to demonstrate how their collections, and the work of their scientists, are helping to solve global challenges. This is as it should be, and it isn’t hard to do. First and foremost these specimens, in the right hands, allow us to name plants accurately. An accurately named plant opens the doors to a wealth of information: its distribution, its uses and its ecology. Effective conservation, sustainable use of natural resources, climate change adaptation, ecosystem restoration – all are dependent on this ability.

The more data, the better

'Why do you need so many of them though – isn’t it enough to have one example of everything?' The answer to this common question is a resounding 'no'.

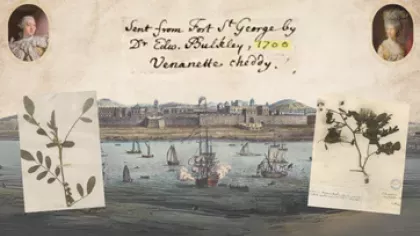

Herbarium specimens are still prepared in much the same way that Sir Joseph Banks was using on the Endeavour, or Darwin on the Beagle. The plant, preferably with flowers and fruits, is arranged and pressed in a sheet of newspaper (Banks was using copies of a commentary on Milton’s Paradise Lost), dried in the sun or over a stove, and ultimately mounted on a piece of card with a label. The label ideally includes a description of the plant, its geographical location (which we can now pinpoint to within a few metres on the Earth’s surface), its habitat, the date, the collector, and sometimes notes on common names and uses, or miscellaneous ecological observations.

Each specimen thus comprises a complex piece of data, and the more data we have access to the better able we are to address our most pressing issues. Each represents a point in time and space for a species (Kew’s oldest herbarium specimen dates back to 1699), allowing us to build up a picture of its global distribution and how this is changing. This in turn allows us to prioritise our research and conservation efforts, and to monitor the effects of global change and habitat loss.

Specimens also tell us at what time of the year plants are flowering and fruiting around the world, and how this may be shifting over time. Many tell us something about the relationship between species and habitats, allowing us to understand ecosystems better, or provide the keys that help us apply plants to human needs such as health and food security.

Challenges ahead

The challenges, now, are harvesting and interpreting this massive ‘database’, and making the information widely and easily accessible. Natural history collections around the world, Kew included, are feverishly ‘digitising’ their specimens for access via the Internet, making high-resolution images and comprehensive databases available for all. For collections the size of Kew’s this is a gigantic endeavour, but in the course of doing so we’re disinterring vital information that’s been lurking behind cupboard doors for decades or even centuries, while facilitating botanical research in countries without access to the specimens.

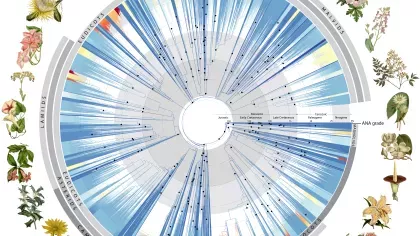

Interestingly, we’re also discovering new species in the Herbarium, some of which may already be extinct. Keeping a collection up-to-date with the latest concepts of names and relationships is like keeping the Forth Rail Bridge painted - as soon as you think you've caught up somebody has proposed a new arrangement. But without taxonomists and curators to do this, the collection soon begins to lose value. At Kew we’re approaching the end of complete reorganisation of the Herbarium, based on new understanding of plant families made possible by molecular systematics (genetic research). Kew scientists were instrumental in the development of the new system, which is based on the evolutionary relationships between plant families and is now in its third revision (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group III, 2009; Chase & Reveal, 2009).

A new generation of taxonomists?

Despite the new tools available for taxonomic work, many families and genera haven’t been revised by specialists for decades, and it’s not uncommon for a specimen to be filed away as ‘indetermined’ (unidentifiable) until somebody with a sufficient knowledge of the group recognises it as something previously unknown to science. In 2012 for example, a Centropogon specimen I collected during a student expedition to Venezuela thirty years ago was finally described as a new species. So it’s not just the specimens and data that are important in biological collections – it’s also the people who maintain and study them. And it’s not just the major collections that are important - smaller ones are vital sources of local information on biological diversity. Taxonomy is as important as it ever was, but increasingly hard to fund and there are ever fewer courses available to train the next generation of specialists. Raising funds for curation is harder still: biological collections around the world are struggling to keep themselves going and many have closed down. Yet we need them, and we need to keep investing in them for the future. However unfashionable they may seem right now, generations to come will wonder what on Earth got into us if we let them go.

References

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x Available online

- Chase, M. W. & Reveal, J. L. (2009). A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161 (2): 122–127. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01002.x Available online

- de Kok, R. (2012). A revision of the genus Gmelina (Lamiaceae). Kew Bulletin 37: 293-329. Available online

- Grande Allende, J.R. & Meier, M. (2012). Novedades taxonómicas en Campanulaceae neotropicales I: dos nuevas especies de Centropogon C. Presl de Venezuela. Candollea 67(2): 233-241. Available online