28 September 2018

From locusts and aloes to the bottoms of ships: looking at a Miscellaneous Report

Kew has received funding from the Wellcome Trust to catalogue and conserve the Miscellaneous Reports Collection. Assistant Archivist Rachael Gardner takes a look at the Natal Miscellaneous volume to showcase the fascinating and diverse material within the Reports.

The Miscellaneous Reports Collection

The volume Natal Miscellaneous is just one of the 771 volumes that make up The Miscellaneous Reports Collection. The Reports include information from across the globe on a wide range of topics, from sugar cane disease in Barbados; forests in Sudan; to silk worms in China. The majority of the material dates from 1850 to 1928 and provides an exciting window into the active role played by Kew in the colonial world, where the transportation and introduction of useful plant products was of central importance, and Kew’s expertise was consulted extensively.

A significant obstacle to discovering and accessing this unique content is the ‘miscellaneous’ nature of the collection. Many of the volumes have vague titles and we just don’t know exactly what is inside. This blog will delve into one particular volume – Natal Miscellaneous – to reveal the fascinating range of material covered, and the benefits that will come from cataloguing and conserving the collection.

Natal Miscellaneous

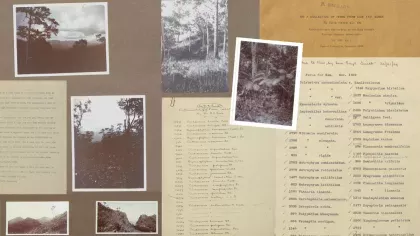

Natal Miscellaneous contains material relating to the Colony of Natal, a British colony between 1843 and 1910, which is now part of the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. It is a scrapbook of printed reports, unique correspondence, early photographs, newspaper cuttings and drawings. The volume comprises 40 sections, covering topics such as rubber, orange disease, cotton, fibre plants, and bananas, revealing information about the cultivation and discovery of these plants and materials. It also demonstrates the internal workings of Kew and its wide-reaching relationships with botanists and the international science community, colonial administrations, and enterprising trade networks.

Rooting around

Samples of plants were often sent to Kew for identification. In 1903 the Director of the Imperial Institute sent a root of a plant ‘employed locally by the natives as a veterinary medicine’ to Sir William Thiselton-Dyer, Kew’s third Director. The letter is annotated ‘undeterminable’ and Thiselton-Dyer explains the difficulties of identifying roots because ‘they have so few distinctive characters that their identification taken alone is practically impossible’. On the paper you can see a faint pencil drawing which looks intriguingly like a root. Could this be a doodle by Thiselton-Dyer?

John Medley Wood and aloes

John Medley Wood was Curator of the Natal Botanic Garden 1882-1903, after which he became the Director of the Natal Herbarium. He is remembered at Kew as the discoverer of Encephalartos woodii, the loneliest plant in the world, which can still be visited today in the Temperate House. This volume contains a significant amount of correspondence with Medley Wood, including an account of his ‘annual botanising trip’, which in 1890 focused on researching further into Natal aloes.

Remaining on the subject of aloes there is also a letter in 1891 from Friedrich August Flückiger (1828-1894), a prolific Swiss pharmacist, chemist and botanist. Unusually, two test filter papers survive with his letter, on which he had ‘strained an alcoholic solution of the sample of Natal Aloes... the solution had been mixed with ammonia and allowed to dry on the paper’.

A delivery of locust eggs, and ‘an enterprising lady'

The volume includes a letter from the Governor of Natal, Walter Hely-Hutchinson, regarding the sending to Kew of a box of normal locust eggs, and a box of locust eggs attacked by parasites. Hely-Hutchinson asks whether the matter can be brought to the attention of Miss Eleanor Anne Ormerod (1828-1901), who was a celebrated entomologist.

In a letter to Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker from the third Earl of Ducie (responsible for creating the Tortworth Arboretum), we hear of ‘an enterprising lady’ who ‘is under the impression that she can grow the olive, if she can procure plants….’

Zulu food plants

A letter sent to Kew in 1897 from Natal’s Colonial Government describes the state of scarcity in Zululand in 1896 ‘due to drought, and to the ravages of locusts’, but remarks that ‘although there was a good deal of suffering, there was not, so far as it is known a single death from starvation…the main source of [the native population of Ubombo’s] food supply appears to have been the seeds, fruits, leaves, and roots of the plants which grow wild in the bush’. A list of these food plants is provided, with each plant’s Zulu name, botanical identification, and notes on the method of preparation.

The Protector Fluid Company Limited

A large section of the volume is devoted to ‘gum euphorbium’, and contains letters, newspaper cuttings and printed material from 1877 to 1886 concerning euphorbias and the production of paints and protector fluids. One such example is the Protector Fluid ‘for COATING SHIPS’ BOTTOMS, BUOYS, and other SUBMERGED SURFACES’ created by The Protector Fluid Company Limited, which, according to its characteristically lengthy Victorian advertisement, will ‘stand good under the varying conditions of temperature, resist the corroding action of sea water, and keep off living organisms’. These printed advertisements provide a window into the competitive and lucrative field of commerce which relied on botanical activity.

Making this information findable

Cataloguing and indexing the Miscellaneous Reports is crucial to make the enormously varied information in the collection findable. Only then can we fully explore the potential of this fascinating collection to transform our understanding of the global networks of plants and economic and scientific activity in the 19th and 20th centuries.

To stay up to date with the progress of the Miscellaneous Reports Project, keep an eye on the blog and twitter feeds, where we will be revealing our discoveries and challenges along the way. This will include part two of this blog post, where Book Conservator Aimee Crickmore will describe her approach to the essential conservation work to preserve the Miscellaneous Reports for present and future use.