17 August 2023

Forgotten peas – future food?

With the world's menu shrinking, it takes a Kew PhD student with a culinary science background to reintroduce us to the future of food.

It’s a relaxing weekend afternoon and you are enjoying your Sunday roast with a side of delicious peas and potatoes. Roast dinner connoisseurs are likely to sample a different meat every week, but how many varieties of peas do you actually eat?

While finding the best wine pairing for your Sunday roast is a more common problem in our minds, the reduction in diversity of food crops (agrobiodiversity) is a serious modern problem that we tend not to think about as much.

After the second World War with the advent of global supply chains, the variety of edible crops consumed by people across Europe and the UK has been narrowed down significantly.

This decrease in agrobiodiversity makes the agricultural system more vulnerable to pests and changes in our climate. More often than not it also means that we’re not getting enough of the important micronutrients that we need for good health, linked to an increase in chronic conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Working on solutions, Szymon Lara is a Kew PhD student with a background in Gastronomy and Culinary Arts. His interest in foraging started in his early years and became quite prominent during his time as a professional chef by creating new flavor experiences.

After becoming interested in agrobiodiversity, he decided to advocate for more resilient food systems by using sensory science to evaluate the commercial potential of neglected and underutilized foods.

The bigger picture: neglected and underutilized foods?

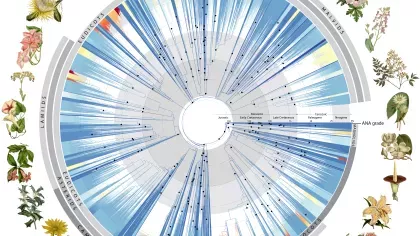

There are around 7,039 edible plant species, 417 of which are considered food crops. However, only 15 account for 90% of human calorie intake and are considered commodity crops.

The remaining 402 are neglected to some extent and are usually found in minor food systems, but even these are shifting too.

Global food chains are tending toward uniformity, leading to the loss of crop and food diversity, particularly of indigenous food cultures and cuisines – a phenomenon termed “Mcdonaldisation” by some social scientists. These so called “forgotten” foods get lost in the ultimate shuffle between the local and global food systems.

Low crop species diversity and the tendency to grow individual crops in vast monocultures reduces the resilience of our food industry. If the entire food market relies on a single crop species/variety, its unexpected decline would have devastating consequences.

This is what happened in the 1950’s when emergence of Panama disease wiped out the entire global market of the ‘Gros Michel’ banana variety. The ‘Cavendish’ variety (Musa acuminata) makes up almost the entire global market today.

The market did not learn it’s lesson since Panama disease now also threatens the Cavendish, and no other banana varieties with the desired characteristics are currently available.

Low agrobiodiversity is also damaging to human health. A variety of health problems have been associated with reduced micronutrient intake. This is worsened by routine consumption of the same foods.

In a nutshell, increasing the number of fresh edible species would improve food security, by decreasing vulnerability to pests, and have beneficial nutritional implications, by introducing species with higher micronutrient absorption rates.

How do we crack all this hidden gastronomic potential?

The supply-demand model means that whether or not the consumer accepts a food plays a key role in promoting agrobiodiversity. The cultivation of a greater variety of crop species will not be effective if there is a lack of public interest in consuming these products.

One of the major factors driving consumer acceptance of a new food is what we call its "sensory profile". This is based on our physiology (our senses and receptors) and our psychology (our past and present experiences, expectations, imagination, mood, and other influences).

In order to understand if a “forgotten” food could be accepted by consumers, we need to study its sensory characteristics. This can be done by using what we call “subjective methods” – bringing together real humans to sample the foods and evaluate their sensory attributes. Alternatively, we have “objective methods” – techniques that describe the physical and chemical make-up of the food, such as ‘texture analyzers’ or infrared spectrophotometers (instruments that can analyse the chemical make-up an object by the amount of light it absorbs).

The combination of these outputs helps us predict whether an underutilized species is likely to be popular.

Can underutilized varieties make it to the market?

Back to those Sunday roast peas! The focus of Szymon’s PhD research is understanding the potential consumer acceptance of underutilized pea varieties. He used both subjective and objective methods to compare the sensory profiles of nine "forgotten" peas against three commercial cultivars.

Interestingly in both cases the “forgotten” peas had higher scores, especially for their texture. Their purchase intention was also higher.

Underutilized species outperforming commercial varieties isn’t new. A similar analysis showed that landrace cultivars of melons are likely to enjoy a 100% acceptance rate since they are sweeter and juicier than their commercial counterparts. In technical terms, they have a superior sensory profile.

Solanum melongena L. (Aubergine), Malus domestica L. (Common Apple), Triticum aestivum L (Common Bean), Brassica rapa L. (Common Cabbage), Lactuca sativa L (Lettuce) and Daucus carota L. (Carrot) are other examples of “forgotten” or gardeners’ landrace varietals that outperform their commercial counterparts based on sensory profiles and gastronomical heritage.

Crop heritage is a particularly strong player here in the UK, where regional variations of well-known foods have held their use through tradition: the northern Carling pea, the Orkney cabbage, and even the once-lost “naked oats” of Cornwall.

What do we take home from Szymon’s work?

Agrobiodiversity is key for our health and the health of the planet, but the efficient global market has reduced the crop species we eat. Reintroducing “forgotten” species will bring health benefits and improve food security, nutrition and dietary diversity. However, consumer acceptance is critical in driving the successful reintroduction of these foods to the markets, making them accessible, affordable and worthy of investment from the food supply chain stakeholders.

Understanding how the sensory profiles of “forgotten” crops compares to the commercial cultivars can aid the successful reintroduction of these foods to food value chains and potentially drive the demand for an even more agrobiodiverse Sunday roast.