23 August 2021

Protecting Earth's ecological puzzle

When it comes to meeting biodiversity and climate goals, we need to choose the right places and the right protection.

Biodiversity, put simply, is all life on earth.

It’s a critical part of human life, supplying us with the oxygen we breathe and providing us with food, water, and medicines.

Biodiversity also regulates our climate.

Each species plays a part in Earth’s ecological puzzle; each one intricately linked to one another and to their physical surroundings.

We’re losing species and habitats at an alarming rate, leaving gaps in the puzzle which are leading to destabilised global ecosystems.

Conserving biodiversity, of course, offers many major global solutions to challenges such as climate change.

Sadly, the world is failing to stem the decline in nature.

As the biodiversity crisis intensifies, we need to assist governments and policymakers in achieving biodiversity targets and, this time, in parallel with climate goals.

A key question that we set out to answer in our recent study, published in Nature, Ecology & Evolution is where in the world, and how much land, should be prioritised for protection to maximise impact and bring the greatest benefits to policy objectives?

Nature Map Earth

The analysis was produced as part of the Nature Map Earth project, an initiative launched by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), International Institute for Sustainability (IIS), the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), and the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN).

A number of partner institutions are involved, including Kew.

We found that properly managing just 30% of strategically located land could safeguard 70% of plant and vertebrate species, while conserving 61% of the world’s carbon stocks and 66% of global water supply.

When that figure is increased to 50%, the benefits are intensified to 79% of species, 85% of carbon stocks, and 90% of all clean water.

The research involved an unprecedented collaborative effort across international institutions, gathering exceptionally large datasets about the global distribution of species, carbon and water, and conducting a wide range of cutting-edge analyses.

Here at Kew, we contributed by putting plants on the map.

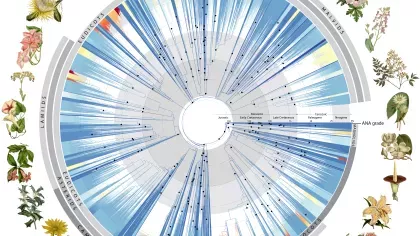

Our life-long expertise in plant species naming, inventorying, and mapping, combined with a more recent focus on statistical modelling, enabled us to map the native distribution of nearly 200,000 plant species.

While global plant diversity was poorly represented in previous conservation efforts, this research allowed us to pinpoint new conservation priorities and obtain a more comprehensive view of nature and its contribution to people.

An integrated approach

This is the first study of its kind and marks an important step towards designing holistic global conservation strategies that concurrently focus on the tremendous diversity of plants, animals, and other natural resources such as carbon and water.

Governments failed to meet the previous biodiversity targets, the 20 Aichi Targets, which were set a decade ago.

Next year, countries worldwide will adopt the ‘post-2020 global biodiversity framework’, a roadmap developed by the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity to bend the curve of biodiversity loss.

Our study could be used as a tool to support policymakers in conservation planning to help meet the targets set within the framework.

Read the paper

Jung, M., Arnell, A., de Lamo, X. (2021) Areas of global value for conserving terrestrial biodiversity, carbon, and water. Nature Ecology & Evolution