15 August 2016

Collections and conservation

Kew scientists Sonia Dhanda and Iain Darbyshire explain how Kew’s herbarium specimens are used to contribute to conservation through the Tropical Important Plant Areas (TIPAs) programme.

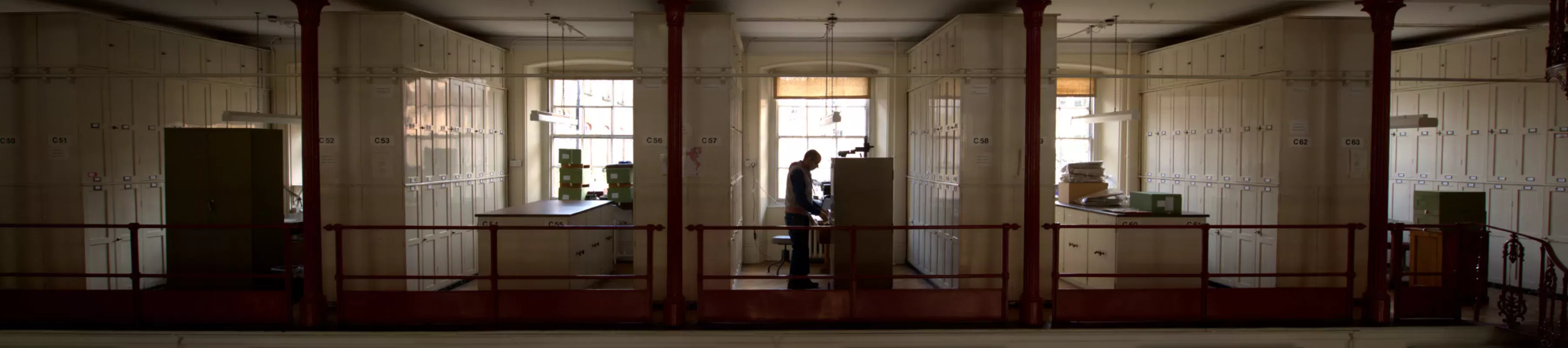

Kew has well over seven million herbarium specimens, which are widely recognised as an important reference collection for plant taxonomy and identification. Additionally these collections significantly contribute to conservation work undertaken at Kew. Here, we highlight how herbarium records feed into evidence-based conservation decisions illustrated through the Tropical Important Plant Areas (TIPAs) programme, one of Kew’s Strategic Science Outputs for 2020.

What are TIPAs?

Certain parts of the world are home to greater plant diversity than others, and, like most natural resources, are under threat from land-use change, climate change and degradation. In the race against species extinction it is important to identify areas that exhibit exceptional plant diversity to prioritise conservation efforts.

This urgent task has led to the Important Plant Areas (IPAs) designation created by Plantlife International which identifies these areas with the following three criteria: threatened species, threatened habitats and exceptional botanical richness. This year the criteria were revised to include socio-economic and culturally important plants to engage with communities, in order to contribute to the long-term sustainability and conservation of these plants.

Since the inception of IPAs in the early 2000s great progress has been made in identifying areas of importance for plants: so far 69 countries have undertaken an initial assessment of their IPAs (Plantlife, 2010). However, as seen from Figure 1, there has been a gap in identifying IPAs in the tropics which led to the launch of Kew’s Tropical Important Plant Areas initiative.

Kew and Plantlife are now working with IPA partners from across the globe to adapt the IPA criteria to the conservation challenges and the data limitations we face beyond Europe, so that we can effectively identify areas including threatened species and habitats in the tropics.

In the first phase of this work, we are focussing on seven countries across the tropics where we have strong existing partnerships and robust data sets: Bolivia, Cameroon, Guinea, Indonesian New Guinea, Mozambique, Uganda and the Caribbean Overseas Territories.

The final output will be to enable national and local authorities to effectively target conservation efforts by designating priority conservation areas.

Currently one in four European IPAs holds no legal protection or active management plan (Plantlife, 2010) and so the greatest challenge after identifying IPAs will be to ensure legal protection. This will be dependent on local networks and national legislation, furthering the importance of working with in-country partners and governments in the early stages of the programme.

Conservation in a diverse country: Mozambique

Mozambique is a country with diverse flora, several areas of endemism and numerous endemic and range-restricted species. The vast diversity of species found in Mozambique stems from the varied landscapes: from Miombo woodlands along the north east coast; mountains with mosaic forests and grasslands along the Zimbabwean border; and the wetlands and estuarine systems in the southern Maputaland region.

As recently as 2005, areas previously unknown to science have been explored in Mozambique, for example the high altitude forests on Mt. Mabu. This area was discovered through Google Earth by Julian Bayliss which led to a biodiversity survey co-led with Jonathon Timberlake in 2008.

Kew scientists have also been active in exploring the northern coastal dry forests in the region of Cabo Delgado, with 36 new and not yet described species recorded from the study area between 2003 and 2009 (Timberlake et al., 2011).

Mozambique was an obvious candidate for the TIPAs programme because of its botanical richness, new discoveries, and the active involvement of Kew scientists working in Mozambique, along with the imminent threats to the flora from agricultural expansion, artisanal mining, illegal logging, wildfires and harvesting of useful plants.

In the early stages of the Mozambique TIPAs project, a preliminary list of endemic and range restricted species in Mozambique were selected using Flora Zambesiaca. This Flora is the product of decades of research on the flora of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, Botswana and the Caprivi Strip (Zambezi Region) of Namibia, and is the essential reference for the plant diversity of this region. Around 800 species, subspecies and varieties of plant have been provisionally classified as endemic and near-endemic using expertise from botanists who have been working in Mozambique in recent years and in partnership with the Insituto de Investigação Agrária de Moçambique (IIAM).

The use of the information held in collections is an essential starting point to determine what the rarest species and their habitats are; where they are known to occur and are likely to occur; and also where the gaps in our knowledge of a country’s flora lie, so that we can target fieldwork efficiently (Romeiras et al., 2014; Greve et al., 2015).

We are databasing collections from herbaria with significant Mozambique collections. These herbaria include Kew, the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical in Lisbon (LISC), National Herbarium of Zimbabwe in Harare (SRGH) and the herbaria of IIAM and the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane in Maputo, Mozambique.

Primarily we record plant locality, date, habitat and traits which feed into the TIPAs criteria. This methodology was developed through the IUCN Sampled Red List Index (SRLI) for Plants, a project led by Kew and the Natural History Museum, London. The scientists involved used collections-based research to assess a randomly selected sample of the world’s plants in order to create a picture of the overall threat status for each major plant group (Brummit & Bachman 2010).

Once the species data are collated and georeferenced we can make preliminary Red List assessments. By working with the IUCN SSC Southern Africa Plant Specialist Group and with botanists who have undertaken fieldwork in the region, we are in a position to assess threats to the species, and assign an IUCN Red List threat assessment to the species.

A previous study by River et al. (2011) demonstrated that using 15 herbarium specimens can confidently provide a preliminary conservation assessment, demonstrating this as a robust scientific methodology.

Collaborating for conservation

From the valuable data collated from herbarium collections, we can further efforts in under-collected areas, collaborate on multi-disciplinary research and prioritise conservation research.

The revised IPA criteria have been aligned with the IUCN’s Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), a designation with overarching criteria applied to all species and biomes to simplify conservation planning for decision-makers. The outputs of TIPAs will contribute to Red List assessments for endemic and range-restricted plants, highlight threatened habitats and areas of plant diversity, but also feed into wider initiatives such as landscape-scale conservation.

Acknowledgements

Much of Kew’s research in Mozambique is funded through the Darwin Initiative, Bentham-Moxon Trust, CEPF and other invaluable funders.

References

Brummitt, N. & Bachman, S. (2010). Plants under pressure a global assessment. The first report of the IUCN sampled red list index for plants. London: Natural History Museum. Available online

Greve, M., Lykke, A. M., Fagg, C. W., Gereau, R. E., Lewis, G. P., Marchant, R., Marshall, A. R., Ndayishimiye, J., Bogaert, J. & Svenning, J. C. (2016). Realising the potential of herbarium records for conservation biology. South African Journal of Botany 105, 317–323. Available online.

Plantlife (2010). Important Plant Areas Around the World: Target 5 of the CBD Global Srategy for Plant Conservation. Available online.

Rivers, M. C., Taylor, L., Brummitt, N. A., Meagher, T. R., Roberts, D. L., et al. (2011). How many herbarium specimens are needed to detect threatened species? Biological Conservation 144(10):2541–2547.

Romeires, M. M., Figueira, R., Duarte, M. C., Beja, P. & Darbyshire, I. (2014). Documenting biogeographical patterns of African timber species using herbarium records: A conservation perspective based on native trees from Angola. PLoS ONE doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103403. Available online.

RBG, Kew (2016). The State of the World’s Plants Report. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online.

Timberlake, J., Goyder, D., Crawford, F., Burrows, J., Clarke, G. P., Quentin, L., Matimele, H., Müller, T., Pascal, O., de Sousa, C. & Alves, T. (2011). Coastal dry forests in northern Mozambique. Plant Ecology and Evolution 144 (2): 126–137 doi:10.5091/plecevo.2011.539 Available online