3 March 2023

Half a century of Kew in CITES

We take a moment to look back and celebrate the achievements of a 50-year partnership related to the legal and illegal trade of wildlife.

A five-decade history

As humans, we move wildlife across national borders daily. It comes in all types of forms – live animals and plants, as extracts, powders, liquids – for a variety of different products, like cosmetics, furniture, ornamentals, and more.

This trade of species has the potential to do real harm to our natural world if it’s not managed carefully. Too much trade can and has contributed to the decline and extinction of populations. So how do you regulate something that would take such a feat of international collaboration?

1973. World governments meet to forge an agreement on how to handle the world trade of endangered species. The outcome: CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora – a means of creating rules to protect wildlife, and enforce them.

Exactly 50 years ago, CITES was signed in Washington D.C. opening up half a century of history with us here at Kew at the heart of it.

A partnership begins

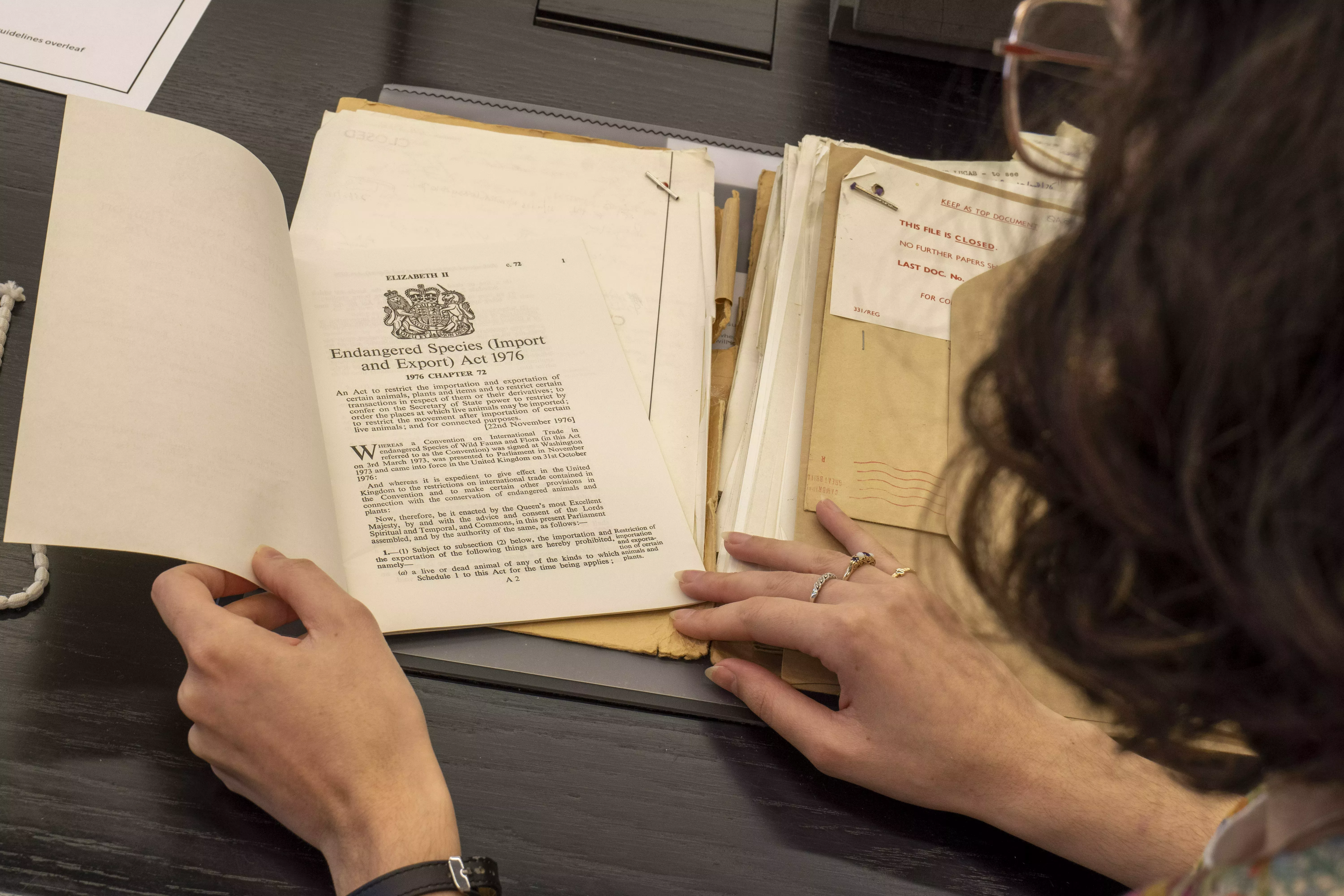

The UK formally joined CITES in 1976. As a participating nation – a party – it needed to endorse one ‘Management Authority’ and one ‘Scientific Authority’ capable of enacting CITES policy.

RBG Kew was proposed as the UK’s Scientific Authority for Flora in December 1975, but digging through our archives, we found that story goes back much further, to the very beginning.

As early as 1973, our former Deputy Directory, John Brenan was championing Kew for the CITES partnership.

“Whatever institution or body is nominally designated as the Scientific Authority for plants in the UK, I have no doubt that it will fall to RBG, Kew, to provide the expertise and to cope with the practicalities of implementing the Convention in so far as it involves plants ”- JP Brenan 1973.

Our life in CITES

What does being the Scientific Authority for CITES actually mean on a day-to-day basis, and how do you truly tackle something so big? We talked to Jess Grey from our CITES team for real look at the challenge.

“On an average day, tens, even hundreds of permits go through Kew. Each needs to be certified that the item is CITES compliant and isn’t likely to be detrimental to the survival of the species in the wild.

"Let’s say a permit for some antiques arrive. This happens all the time. One of our favourites to pass through was a permit for a rare collection of Japanese netsuke – tiny, intricate figurines made of materials like wood or ivory.

"The first thing we do is identify the species that’s being imported or exported. Which exact tree species were used to make these tiny statues?

"From there, our job is to search through all the potential reasons the trade might not be compliant. If the wood used has come from a tree species that can’t be collected from the wild but can be grown or artificially propagated, we’d need to see evidence of a nursery or a management plan for the plantation that the species has been sourced from. Perhaps there’s a ban on the export of this species through national legislation to consider too.

"One of the most important checks is the conservation concern. Are the tree species used for these netsuke considered endangered on the IUCN Red List? Are there other biological risks involved with the harvest of these trees? Is the trade in them actively known to cause harm to the species and those associated with it in the wild?

"Ideally – and in most cases – the answer to all of these questions lands on the right side of yes or no, and sustainable trade can go ahead with a permit.

"When it doesn’t, we will first try and obtain some more information from the applicant to cover any gaps in evidence, such as photo proof of source. If there are still issues, that’s when we notify the UK’s CITES Management Authority that we cannot give our scientific approval to this particular trade. It's then up the Management Authority to determine whether or not a permit should be issued.

"We call this whole process an NDF – a non-detriment finding. They’re a legal requirement as a designated CITES Scientific Authority, and we handle hundreds each and every month.”

Modern world – CITES future

CITES and the people implementing it can only act on evidence. In the modern world, there are more species being discovered daily, and likewise more species being traded than ever before on the global markets.

Often, a tree commonly traded for timber may turn out to be three species, one of which is far more threatened than the other two.

To ensure those implementing CITES on the ground don’t have an impossible task, CITES has “checklists” of entire species groups of plants. We at Kew have been responsible for the creating some of the very first.

The most recent achievement at Kew was an electronic checklist for all 275 accepted species in the genus Dalbergia. These plants are the rosewoods, used worldwide from everything from charcoal to musical instruments.

Our work to check the conservation status of all Dalbergia species, their current known range across the world, their uses within individual countries, and the imminent threats to survival, means the information exists to identify the correct species in any given situation and assist in decisions on sustainable international trade.

We hope our partnership of 50 years lasts another, and grows from strength to strength!

John Scanlon, a trustee of RBG Kew and the CITES Secretary-General (2010-2018) puts it best.

“RBG Kew has been the UK's Scientific Authority to CITES ever since the Convention came into force, and it continues its outstanding work today. With many plants and fungi around the globe still in need of international protection, and countless new species being discovered year on year, I hope that this partnership is one that lasts for the next 50 years and beyond.” John Scanlon, CITES Secretary-General 2010-2018.