26 February 2016

A brief history of plants in books

People have stored pressed plants in book bindings since the 16th century. Book conservator, Sarai Vardi, discusses the historical relationship between plants and bound volumes.

The first pressed plants

Luca Ghini (1490–1556), an Italian botany professor, is considered to have been the first person to press and dry plants, and mount them onto paper. His process allowed plants to be preserved as a record and studied in seasons when they would normally be dead, heralding the way for herbaria around the world.

Ghini taught his technique for collecting, pressing and mounting plant specimens to his students at the University of Bologna and was very well received. News spread fast and by the mid 1500s Ghini’s art of preserving and storing dried plants was spread all over Europe.

Traditionally, herbarium collections were kept in bound formats, where plants were mounted to the pages of a volume, stored in a library, and cited like books. These albums of dried plants were known as hortus siccus (literally ‘dry garden’) or hortus mortus (‘dead garden’).

Interestingly, the term 'herbarium' was originally used in the 18th century – not for preserved plant collections, but rather for books about medicinal plants. French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort was the first to substitute the term 'herbarium' for hortus siccus.

To bind or not to bind?

From a botanist’s perspective there are pros and cons to storing your plant collections in books. Books are easy to store and shelve, and individual specimens are less likely to be lost or stolen from a binding. Shut bindings can also protect specimens from pollution, light and dirt, resulting in better preserved plants.

However, the inelasticity of bound collections can be a real problem: once mounted in a volume, the order of the plants is fixed. Specimens cannot be easily removed or re-ordered to accommodate new findings or arrangements. Also, the flexing and turning of pages can damage fragile plant specimens, causing fractures and detachment.

Birth of the modern herbarium

The Swedish 18th-century naturalist Carolus (Carl) Linnaeus was one of the first botanists to move away from the tradition of storing plant specimens in books and instead preferred to leave his herbarium unbound. Linnaeus mounted his specimens on loose sheets, stacking them horizontally and systematically in purpose-built cabinets. This meant that if new specimens were discovered, they could easily be inserted into the correct location. Plant collectors followed Linnaeus’ lead and there was a mass move away from keeping bound herbaria. To this day, specimens in Kew’s herbarium are mounted onto individual archival paper sheets and stored flat in purpose-built cabinets in climate-controlled buildings.

However, the tradition of storing pressed plants in books was continued by individuals for private use. By the 19th and early 20th century, bound herbaria were typically made by upper class students as a supplement to their botanical studies, and as a popular Victorian craft.

The term 'exsiccata' was first used in the 1800s to mean simply 'a collection of pressed plant specimens’. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew was the first to use the term to mean explicitly 'a collection of specimens, bound into a volume for the purpose of library cataloguing'. This new terminology made a clear definition between bound and dis-bound herbaria.

It wasn’t just botanists who created exsiccatae, as can be seen by Kew’s varied collection. These volumes were also a pastime of artists, poets and tourists (who created them as souvenirs), and were considered one of the 'accomplishments' of the Victorian lady. An example can be seen in my previous blog post on exsiccata (link below).

'Sticker books' for plant lovers

Publishers also cashed in on this growing interest in plants by printing limited edition runs of books with pre-collected plant specimens already mounted to the pages. Alternatively, hobbyist botanists could buy books containing printed descriptions of particular plants with blank spaces to insert their own collected and pressed specimens. These volumes could be compared to modern day football sticker books, but for plant lovers.

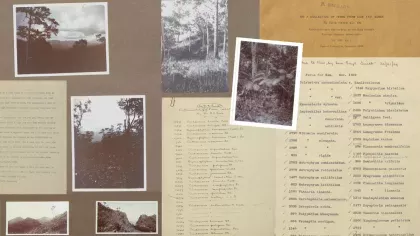

The majority of Kew’s exsiccatae are housed in some form of bookbinding. However, other forms include mounted specimens assembled into a boxed and labelled volume or portfolio. Kew does have published examples such as Treasures of the Deep, although the majority of our exsiccatae are individually assembled and contain a rich and diverse mix of plants, some of which you would never think possible to press and keep in a book.

- Sarai Vardi -