23 November 2023

Worth a thousand words: The hidden histories of botanical illustrations

From field sketches to Herbarium commissions, botanical illustrations are deeply entangled with the history of science.

Writing to Henry Ridley, Kew’s former Director Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911) said of another scientist 'his drawings are not good enough to help much… They are in a terrible mess and I do not see my way through them.'

Even though botanical illustrations are still invaluable today, nineteenth-century botany was even more heavily reliant upon them, due in part to the difficulty of preserving fragile specimens. This meant precise detail and accuracy was particularly important, but what this looked like varied considerably between different botanical artists.

The ways in which sketches were produced, viewed, and commissioned depended upon the technologies available. The broader political context in which these works were created also impacted on the information that was shared about some plants.

Existing at an intersection between commercial value, aesthetics, and scientific research, botanical illustrations occupy a complex role in the history of science.

Flora von Deutschland

The Flora von Deutschland series is a compendium of botanical illustrations first published in 1885. It represents a more formalised compilation of botanical illustrations detailing Germany’s plant life, seeking to provide a comprehensive taxonomic guide for a growing wave of amateur botanists and others working with plants.

The illustrations in these books were painstakingly crafted to present lifelike representations of the plants in the book. At the time, images like these were controversial, with some scientists claiming that images are inherently less accurate than their long, text-based descriptions of plant characteristics.

Word-based depictions are not as neutral as they might seem. The use of Latin descriptors, for instance, was less accessible to people who didn’t have a formal education. What’s more, these rejections of botanical art are also often gendered. Historically, the work of illustration was often associated with women and consequently their intellectual contributions were sometimes belittled.

In the details

The inclusion of details such as cross-sections, annotations and specific features makes clear the scientific value of these drawings. In depicting plants, botanical artists can decide which essential elements to include, moving beyond simply reproducing an existing object, and taking part in a scientific process through which critical features can be explored.

These books therefore present illustrations that are at once art and science, combining descriptive text with imagery in the pursuit of accuracy though – as always – contextually limited.

Several Flora von Deutschland volumes can be found on the Biodiversity Heritage Library website, for those interested in further reading or illustrations.

Field sketches

In contrast to the carefully polished illustrations of Flora von Deutschland, these field sketches from Elsie Wakefield (1886-1972) were produced directly in the process of scientific exploration.

Wakefield was a mycologist credited with naming numerous fungi species and was Deputy Keeper of Kew’s Herbarium between 1945 and 1951.

In her work, the entanglements between science and art are clearly apparent, through the extensive annotations lining the page surrounding her watercolour sketches. Unlike published works, these drawings were in a sense intensely personal, forming foundational notes to be later used for more detailed sketches and taxonomical work.

Through them her personal style is clearer than in her published work, revealing her as an artist as well as a formidable botanist.

Interestingly, her inclusion of some of the grass and soil the mushrooms are a contrast to the traditional approach of presenting the specimen alone on a page. By including these elements of the wider habitat, her sketches challenge standard practice, and raise questions as to what is scientifically valuable enough to be included in depictions.

Letters and illustrations

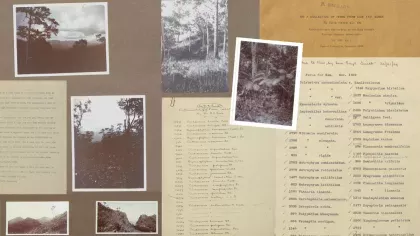

Joseph Dalton Hooker relied significantly upon botanical illustrations to conduct Herbarium work while physically isolated from the site at which the specimens he was examining were growing.

Later in his letter, he stated 'The Calcutta collection of drawings of orchids has been invaluable … If you could get us copies of yours at a moderate rate, I do not doubt that the Herbarium would pay.'

It’s clear that botanical illustrations were clearly regarded as scientifically precious, worthy of purchase.

The financial dynamics behind these sketches, however, cannot be divorced from the purposes for which they were created. Taxonomic work of this period was thoroughly entangled with economic value. In short, the commercial side of botany shaped the illustrations that were produced, prioritising those that would make money.

Local knowledge

Rarely integrated when creating new illustrations in the field, local knowledge was disregarded in favour of a blank-slate project of ‘discovery’ and categorisation. For example, the Calcutta Botanical Garden employed the labour of local artists, but instructed them in Western forms of representation, as this was the primary audience for their sketches.

The surviving work of such artists reveals a lot about the ways in which the circumstances of production influence the art, with distinct non-Western artistic influences shining through.

As the digital archiving summer intern, I’ve been fortunate to work with several kinds of botanical sketches over my time here. The above represents a fraction of the collection, not even delving into the mass of work held by the illustrations department.

Botanical illustrations still have a role to play today, as an example in 2022, the artwork of Lucy T Smith was a key part of the discovery of a new waterlily species at Kew Gardens.

For any interested further in botanical illustrations, whether intrigued by critical art histories or simply aesthetically compelled by the linework, I thoroughly recommend a visit to Kew’s Shirley Sherwood Gallery.

Bibliography

- Dyson, J. (2003). ‘Botanical Illustration or Flower Painting: Sexuality, Violence and Social Discourse’, Colloquy, 7, pp. 1-7.

- Saunders, G. (1995). Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration, United Kingdom: Zwemmer.

- Tobin, B.F. (1996). ‘Imperial Designs: Botanical Illustration and the British Botanic Empire’, Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, 25, pp. 265-292.