4 July 2022

Uncovering the giant waterlily: A botanical wonder of the world

A plant giant has been named new to science at Kew after spending 177 years hidden under the surface of our collections.

A breaking botanical discovery has come to light, as the famous giant waterlily genus Victoria welcomes a new species.

Victoria boliviana, has been sitting in Kew’s Herbarium for 177 years, previously mistaken for Victoria amazonica, the waterlily named after England’s Queen Victoria in 1837.

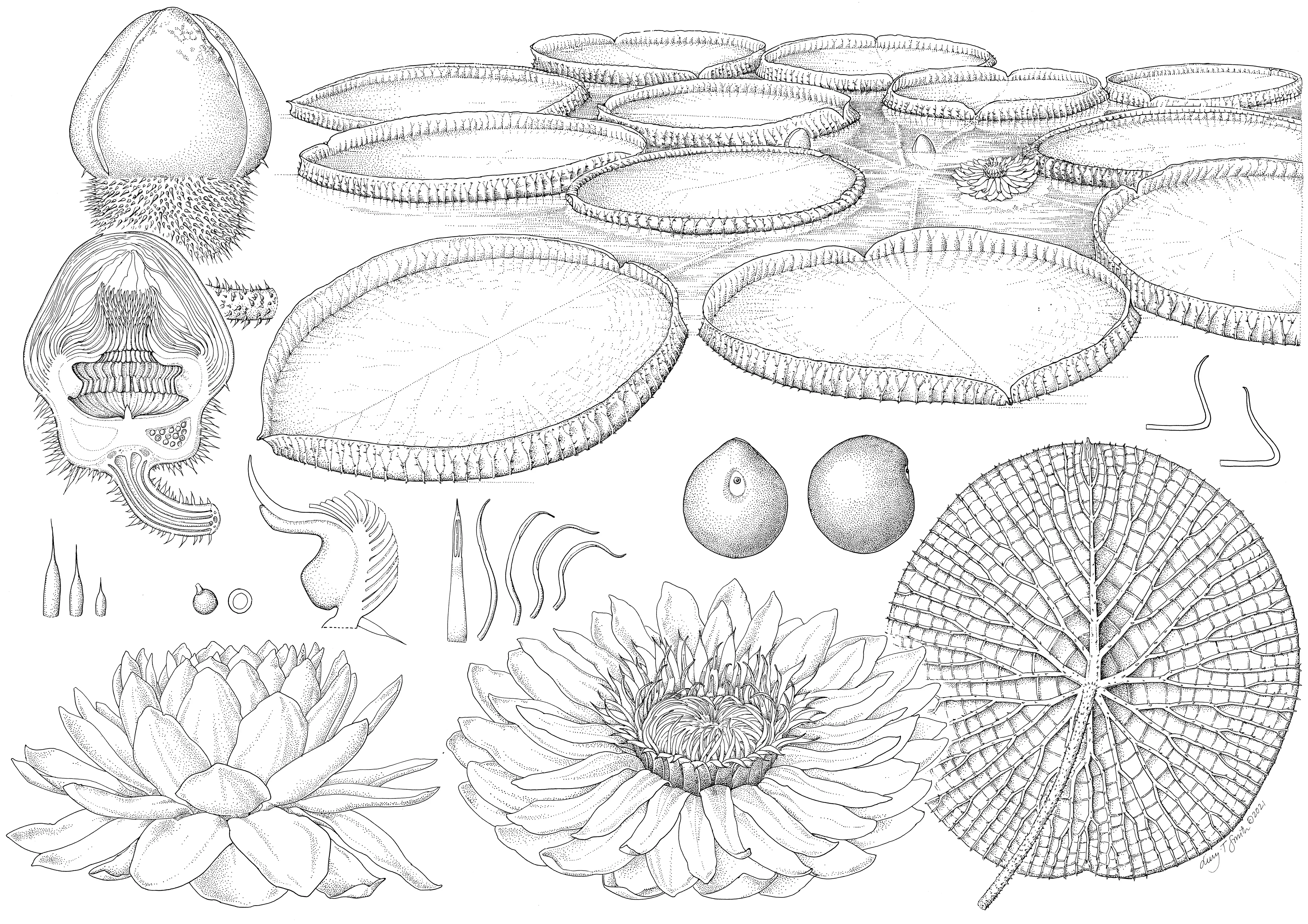

A team of world experts in Science, Horticulture and Botanical Art have scientifically proven that Victoria boliviana is a new species to science using novel data and their unique mix of expertise.

Record-breaker

This is the first discovery of a new giant waterlily in over a century. But the surprises don’t end there — V. boliviana is now the largest waterlily in the world, with leaves reaching 3 metres wide in the wild!

The current record for the largest species is held by La Rinconada Gardens in Bolivia where leaves grew to 3.2 metres.

Victoria boliviana is native to Bolivia where it grows in one of the largest wetlands in the world, the Llanos de Moxos in the Beni province, which is also home to the Bolivian river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis ssp. boliviensis) and Critically Endangered blue-throated macaw (Ara glaucogularis).

It produces many flowers a year but they each open in turn, one at a time, and for just two nights, turning from white to pink and covered in sharp prickles.

The underside of their leaves is also a sight to behold, resembling a cross between a suspension bridge and the roof of an old cathedral.

The road to discovery

After suspecting for years there was a third species in the Victoria genus (alongside V. amazonica, V. cruziana), Carlos Magdalena, a world expert on waterlilies and one of Kew’s senior botanical horticulturists, began making enquiries to gardens in Bolivia.

In 2016, Bolivian institutions Santa Cruz de La Sierra Botanic Garden and La Rinconada Gardens donated a collection of giant waterlily seeds from the suspected third species.

As Carlos grew the seeds back at Kew, watching the waterlily grow side-by-side with the two other Victoria species, he knew immediately something was different.

Victoria boliviana has a different distribution of prickles and seed shape to other members of the Victoria genus, making it distinct.

A botanical Rubiks cube

In 1832, V. amazonica was the first species to be named in the genus but due to a lack of data, we’ve been unable to make comparisons against any new species found since — a factor which led to the original misidentification of the new waterlily.

So, with the goal of improving knowledge of Victoria, the paper's authors compiled all existing information using historical records, citizen science (including social media posts), and specimens from Herbaria and living collections around the world.

Kew Scientists also analysed DNA to show that V. boliviana was very genetically different from the other two species.

Together, the data collected confirmed what the authors suspected – that there was another species in the Victoria genus, joining V. amazonica and V. cruziana.

Describing new species to science is crucial to conservation efforts in the face of biodiversity loss and climate change.

Painting a picture

Another of the paper’s authors, Lucy Smith, one of Kew’s freelance botanical artists who has been working with our scientists for over 20 years, has created contemporary scientific illustrations of Victoria.

As the flowers of giant waterlilies only open at night, Lucy made many nocturnal vigils to Kew’s glasshouses to capture the flowers for drawing and painting.

Something that particularly caught her eye was the similarity between the new plant, and the one which Kew artist Walter Hood Fitch drew from a specimen collected in Bolivia in 1845. In fact, it proved to be the same one, unknown as a new species to Fitch at the time!

Dive into Kew this summer

Kew’s Waterlily House was built originally to house the natural wonder of the Victorian age, the giant V. amazonica.

It has amazed visitors for decades with its huge circular leaves strong enough to support the weight of a small child.

Today, it is home to the new species V. boliviana, along with other waterlilies and aquatic plants.

Don’t forget to head over to our Princess of Wales Conservatory too — the only place in the world where you can see these three species of Victoria side by side.