23 June 2023

How Kew inspired queer icon Virginia Woolf

From 'Orlando' to her idyllic short story 'Kew Gardens', Virginia Woolf crafted her critically acclaimed works on our doorstep

The author of Mrs Dalloway (1925) and A Room of One's Own (1929), Virginia Woolf is still one of the UK's best-known writers.

Woolf was a London native who lived within sight of Kew for nearly ten years and became a frequent visitor. She scattered references to Kew into many of her novels, including Night and Day (1919), Orlando: A Biography (1928), The Years (1937) and Between the Acts (1941).

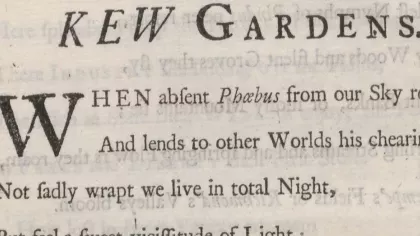

It's clear she loved Kew from the first paragraph of her short story, Kew Gardens (1919):

From the oval-shaped flower-bed there rose perhaps a hundred stalks spreading into heart-shaped or tongue-shaped leaves half way up and unfurling at the tip red or blue or yellow petals marked with spots of colour raised upon the surface; and from the red, blue or yellow gloom of the throat emerged a straight bar, rough with gold dust and slightly clubbed at the end.

The petals were voluminous enough to be stirred by the summer breeze, and when they moved, the red, blue and yellow lights passed one over the other, staining an inch of the brown earth beneath with a spot of the most intricate colour.

A gardener at heart

Woolf and her husband Leonard lived on Richmond’s Paradise Road, close enough to see the top of the Great Pagoda.

We don't know where exactly in the gardens Kew Gardens is set; it might be near Pagoda Vista. Our only clues are a reference to a 'Chinese pagoda', mention of the Palm House roof and a conversation about the Tea Pavilion, which was once burned down by suffragettes in 1913 and is now the Pavilion Bar and Grill. A more detailed scene appears in Night and Day, following two lovers as they stroll under the majestic trees of Syon Vista.

Woolf’s affinity for gardens is woven through her work, from the lush descriptive passages in To the Lighthouse (1927) to the chronicles in her diaries of the gardens she created with her husband. Amidst her severe mental health struggles, she carefully noted what was in bloom up until she took her own life in 1941, at the age of 59.

Painting with words

Kew Gardens captures several everyday conversations overheard on a sunny afternoon in the Gardens.

Woolf focuses in on a snail in a garden bed and the kaleidoscopic colours of the flowers, then zooms out to listen in on people chatting: about the tea rooms, about other visitors, about World War I and lost loves. It’s not so much a narrative with a plot as it is an Impressionist painting in words.

The first editions were self-published in 1919 by the Hogarth Press, which began as a hand press set up in the Woolfs’ dining room. Woolf's sister, the artist Vanessa Bell, contributed two woodcut illustrations. A wider release was printed in 1921 in Monday or Tuesday, a collection of short stories; in 1927 came a third edition with updated illustrations from Vanessa.

Kew holds first and third editions of Kew Gardens in the library and archives collection, which are available to view by appointment and feature the original illustrations. You can also find copies of Kew Gardens in the Kew shop, with enchanting new illustrations by Livi Mills (below).

The Bloomsbury set

In Kew Gardens, Woolf was also experimenting with formalism: an art movement promoted by her friends, the art critics Roger Fry and Vanessa’s husband Clive Bell. They were part of the circle of upper class London artists and intellectuals known as the Bloomsbury set.

Influential and progressive, they could cheerfully ignore the strict morality of the early twentieth century thanks to their wealth and backgrounds. Vanessa lived openly with her lover, the bisexual artist Duncan Grant, who had a child with her and later moved his male partner in with the family.

It was at one of the Bloomsbury set’s dinner parties that Woolf met Vita Sackville-West – writer, future designer of Sissinghurst Castle Garden and self-described ‘sapphist’ – in 1922. Their relationship has been well documented from their diaries and passionate letters.

Letters of note

Sackville-West’s 1926 letter beginning ‘I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia’ especially captured the hearts of queer people everywhere, with its intensity and longing.

Woolf based the gender-fluid protagonist of Orlando on her lover; when Orlando triumphantly claims back their ancestral home, it’s a nod to Sackville-West’s grief over losing her family’s estate of Knole to a male cousin.

The two writers flirtatiously compliment each other’s work in a scene set at Kew (but filmed elsewhere) in the 2018 film Vita and Virginia.

Nature for all

Through Woolf’s turbulent life, gardens were always in the background.

She could study them to practice capturing the tiny details of nature in writing; she could project onto them any mood required for any scene. Perhaps she appreciated the chance to forget her troubles and work with her hands.

In nature, queer people throughout history have always been able to find a place to belong.