8 December 2017

Putting the world's plants on paper: Joseph Dalton Hooker and his scientific publications

As the celebrations for Joseph Dalton Hooker’s bicentenary year come to a close, Cam Sharp Jones explores Joseph Hooker’s scientific publications and the process through which these works were produced.

Floras of the world

The publication of taxonomic Floras – books and articles that systematically describe the plants of a country or region – is by no means a quick and easy process. As a previous Kew Science blog has demonstrated (see blog link below), these works can run to hundreds of pages and must constantly adapt to new botanical discoveries.

In some cases, Floras can take decades to produce, and yet they remain a fundamental and vital part of botanical science and botanical identification.

Joseph Hooker and his publications

During his illustrious career, Joseph Dalton Hooker published over 20 works on the flora of the world. His first major Flora, Flora Antarctica, was published in 1844 as part of his account of the botanical discoveries of the Ross Expedition to Antarctica (1839-1843). This publication was followed by two more Floras in the same series – Flora Novae-Zelandiae (1855) and Flora Tasmaniae (1860).

In the same year that the second part of his Antarctic Flora was published, Hooker co-authored Flora Indica, detailing the results of his expedition to Sikkim and the Himalayas between 1847-1851. This was followed in 1872 with The Flora of British India which drew on his own research and that of other botanists who had worked on Indian plants. This is still one of the more comprehensive floras of India in existence, nearly 150 years after its publication. It is a testament to the endeavour producing such a work requires that it has not been bettered in that time.

Hooker also produced large scale taxonomic monographs that aimed at organising the world’s flora into a systematic structure. Starting in 1862, Hooker and George Bentham published Genera plantarum ad exemplaria imprimis in herbariis kewensibus servata definite, which ran to three volumes, the final one of which was not published until 1883. The Index Kewensis, aimed at registering all botanical names, was established by Hooker and Benjamin Daydon Jackson in the early 1890’s, having received financial support in Charles Darwin’s will. Index Kewensis continued under different editors and remains influential as part of the International Plant Names Index (IPNI) still maintained by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew to this day.

“I am driven distracted…”

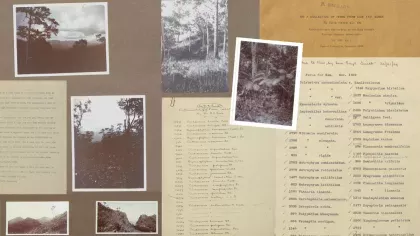

Hooker’s botanical publications are impressive, and the final published works are important documents. From the extensive correspondence written by Hooker, now in Kew’s Archives, we can gain a better understanding of the pressures that Hooker faced when trying to bring these works to completion.

In a letter dated the 4th March 1882 to Asa Gray, the noted American botanist based at Harvard University, Hooker details the breadth of writing he was undertaking. We learn that he had finished working on the ‘Apocynaceae family for the Flora of British India’ whilst also working with George Bentham on the proofs for the Orchidaceae family. In the same letter, he goes on to state that “I am now at Asclepiadaceae, an awful job, & requiring incessant dissection. I have had to make it to keep one of Blume’s genera in Periplocoideae that Bentham had suppressed & to make a new one besides. I tremble to think what I shall have to do as I go on: what with plants or groups that keep their habits, but modify their gynostegia to please insects, & plants or groups that keep their gynostigii characteristics & change their habits to please themselves - I am driven distracted. Meanwhile I shall complete part IX of the Flora…”. Whilst botanically detailed, this letter still manages to convey to anyone who has ever felt overworked, botanist or otherwise, the frustration that Hooker sometimes felt when trying to organise the world’s flora.

In another letter to Gray sent in 1880, Hooker states that “Bentham has just done the Orchideae, & talks of doing the Gramineae! - I am toiling at the Palms, the hardest work I ever had. I have only done 50 Genera in 6 months, & many of these are imperfectly known” (Harvard University Asa Gray Letters, Joseph Hooker to Gray, dated the 8th August 1880).

Whilst such letters clearly show the labour-intensive nature of collating these works, the letters also illustrate how well-read Hooker was on the subjects he was working on. He states in the same letter that “I find Wendland’s work remarkably careful & good. I am glad to say Scheffer (a great loss) also did well, Beccari has massed his predecessors' work. Martius of course is splendid but had no material for the Arecaceae.” All four botanical authors mentioned in this single sentence produced extensive monographs on the plants of interest to Hooker and he was clearly familiar with all their writings.

Hooker's letters also show that the process of publishing his botanical research was laborious and required dedication, often having to adapt to new publications and their taxonomic organisations. In 1882, Hooker once again writes to Gray that “We have begun at last to print Palms for Gen[era] Plant[arum] & just after the refs went to press the 20 parts of Drude in Martius comes out; happily involving no serious changes, if any. Drude has not the grip of them that Wendland has” (Harvard University Asa Gray Letters, Joseph Hooker to Gray, dated the 23rd October 1882). This letter also shows that the taxonomy of palms that Hooker had been working on in 1880 had taken two years to come to print.

“Almost life-long tasks that I have in hand…”

Whilst Hooker’s letters show the strain that producing such important scientific works put on him and his co-authors, they also show his dedication. From one letter to Sir John Lubbock regarding whether Hooker would take up the position of President of the Linnean Society, Hooker writes that “when I resolved upon retirement from official life and work, it was from well considered principles from which I cannot depart. These included severance from active participation in the labors of Scientific Societies, as an absolutely essential condition for concluding some at least of the almost life-long tasks that I have in hand.” (JDH/2/17 f.85-86)

These life long tasks included a Handbook to the Flora of Ceylon and Index Kewensis. Upon retirement, Hooker remained active, publishing over 15 books and articles on the plants of the world between 1885 and 1911. Whilst these works remain important documents in the history of botany, Hooker’s correspondence provides a fascinating peek behind the scenes of the processes of writing and publishing nineteenth century botanical floras and taxonomic works.

Joseph Hooker’s letters and publications are available to view in the Library, Art and Archives Reading Room at Kew, open Monday-Friday 10am-4pm.