24 April 2015

Nonsense in the Archives

Letters by nonsense writer and ornithological artist Edward Lear — found in Kew's Archives — led to an exploration of Lear’s lesser-known talents as a botanical artist and travel writer.

Lear, the nonsense writer

The letters in our Archive collection come from people all around the world and all walks of life. Among them are eminent botanists, scientists, artists, and also the occasional poet and writer. Even in such company, it has been a delight for me to find a series of letters from Victorian writer Edward Lear.

Lear is probably best known today as a nonsense writer and poet from the era of great Victorian children’s literature, alongside the likes of Lewis Carroll's recognised classic Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Yet he had many other — often overlooked — talents. He began a successful career as a natural history painter, and in his later life became a great travel writer and landscape artist. His fascination with the natural world is present in much of his work, and its influence can also be found in his famous nonsense verses and alphabets which he created throughout his life.

Lear, the botanical artist

Lear was a gifted artist and from a young age he began to develop a precise and detailed style of zoological illustration. His ornithological accuracy and talents earned him employment with the Zoological Society, and later the patronage of the Earl of Derby who employed him to record all of the birds of his personal menagerie. He was just 19 years old when he published his first book in 1830: Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots.

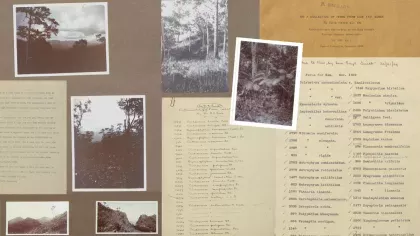

Lear also continued to follow his own scientific and botanical interests in his art, and practiced botanical illustration for his own pleasure as well as reference material which he used to create accurate backgrounds for his bird paintings. Letters from Lear to Sir Joseph Hooker in our Directors’ Correspondence collection — sent between 1872 and 1878 — demonstrate his desire for scientific accuracy as they discuss the identification of ten paintings of Indian trees Lear had been commissioned to paint. Lear describes this desire to correctly label them ‘on the principle of “what is worth doing at all is worth doing well”’ (DC 143 f. 532) and he thanks Hooker for his advice, seeing him as a ‘scientific guarantee’ of the accuracy of his work (DC 143 f. 536).

Lear, the traveller

Due to his failing eyesight fairly early in his life, Lear chose to give up his natural history painting and illustration to focus instead on his travel writing and landscape painting. He travelled to Egypt, the Middle East, Greece and India, before settling in Italy at the end of his life. He sketched during his travels, and from these drawings he created watercolours of the landscapes.

His journals and published travel writings record his excitement and pleasure in the natural splendour he discovered, and writing to Hooker from Darjeeling in 1874, he describes a ‘wonderfully beautiful place’ (DC 153 ff. 360) and laments the following year; ‘Alas! The having seen all those beautiful and wonderful sights seem sadly balanced with the not seeing them anymore!’ (DC 147 f. 651)

Nonsense botany

Despite his many other talents, Lear is now most widely known for his wit and humour in his nonsense literature, from his limericks to spoof recipes and children’s prose. Lear’s humour slips into his letters with Hooker, as he ends one written from his Italian villa: ‘O please have some rheumatism or mild bronchitis, and be obliged to come visit!’ (DC 147 f. 651)

Lear’s ongoing interest in natural history and botany is also evident in his nonsense work. Animals and imaginary creatures creep into many of his rhymes and stories, and his series of nonsense botany sketches play on the rigid naming and taxonomy of the scientific world. This playfulness contrasts Lear’s scientific seriousness regarding his botanical paintings. He mimics the Linnea system of naming plants, but uses everyday objects including teapots and clocks, as well as the more exotic tigers and cockatoos, to create these imaginary plants.

Among Lear’s other fragments of nonsense prose are descriptions and sketches of several fantastical species of trees such as the Biscuit Tree which ‘when the flowers fall off, […] the tree breaks out in biscuits’ (Edward Lear, Selected Nonsense, p. 103). While the ‘fearful and astonishing vegetable’ - the Kite Tree - ‘does not appear to be of any particular use to society, but would be frequented by small boys if they knew where it grew’ (Edward Lear, Selected Nonsense, p. 104).

A friend of Kew

Lear may not be one of the most famous men of this period, but finding him writing to Hooker so animatedly about his travels, and so earnestly about the identifying of plants, ties yet another culturally fascinating figure to this age of scientific exploration, and to Kew as a centre of it.

- Alice Evans -

Archives Graduate Trainee

Further reading

Letters in the RBG Kew Archive, Directors’ Correspondence Collection

Lear, Edward. ‘Over the Land and Over the Sea’ Selected Nonsense and Travel Writings. Great Britain: Carcanet Press Limited, 2005

Mayo, Hope, ‘The Edward Lear Collection at Harvard University.’ Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 22: Numbers 2 – 3, (Summer-Fall 2011)

McCracken Peck, Robert, ‘The Natural History of Edward Lear.’ Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 22: Numbers 2 – 3, (Summer-Fall 2011)