14 April 2016

Latin American lonely hearts

Find out about lonely hearts from Latin America in the Directors' Correspondence Archive Collection.

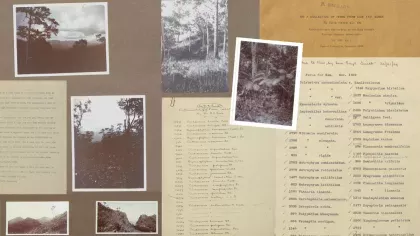

Our Assistant Archivist Michèle recently blogged about love in the archives to coincide with Valentine's Day. This got the Director's Correspondence team talking about the theme in our collection. However, it was not love we ended up noting, but the loneliness experienced by some botanical collectors as they ventured into sparsely populated and inaccessible areas in South America, the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean in search of plant wonders. During their travels they often ventured truly off the beaten track.

In the 19th century, botanical stations were established on many of the West Indies islands. A significant proportion of our correspondence concerns these outposts, which functioned variously as plant nurseries, experimental plots, exchange posts and educational tools. When seeking new employees, the Directors of these stations or the local Government would write to senior staff at Kewfor advice listing the sort of qualities they desired in an employee. Many such letters express the desirability of a married man!

In 1890 William Fawcett, Director of Public Gardens and Plantations in Jamaica, writing to Daniel Morris then Assistant Director of Kew, remarks upon the loneliness of the Cinchona botanic station. He already had to repost one gentleman owing to isolation and was now looking to employ a man who has 'plenty of occupation of his own in the evenings' (DC 210, f.255).

Robert Hermann Schomburgk (1804 - 1865) was an explorer and naturalist celebrated for his surveying work especially in British Guiana . He was knighted by Queen Victoria and worked in various official capacities, including a posting as the British consul to Santo Domingo.

From there we have a detailed and moving letter from Schomburgk in 1850 to William Jackson Hooker, then Director of Kew (DC 70, f.290). He feels that he now stands 'alone growing old, and have no person with whom to exchange my ideas, whom[?] to cherish'. He has frequently thought that he 'threw one chance away, and this was when you [Hooker] put the two Misses W. under my protection: the elder of whom, I thought pretty and most amiable'.

Unfortunately we do not know the 'Miss W.' to whom Schomburgk refers and he never married. In the same letter Schomburgk remarks that 'these are petty confessions and nothing to do with science at all – nor do I know how they flew into my pen'. However, his confessions offer a candid opinion amongst a collection often formal in tone.

In spite of their often isolated situations and the great distances that separated correspondents from loved ones in Europe it is frequently apparent in the correspondence that it was the love and enthusiasm for their work which spurred gentlemen like Schomburgk on. Colonel Richard Clement Moody, Lieutenant Governor of the Falkland Islands in the 1840s writes to William Jackson Hooker on many occasions mentioning tussock grass. Moody chastises himself for dwelling on the subject but notes that his 'heart is always full when he thinks of it' (DC 70, f.205).

Doubtless the communication with colleagues and friends afforded by steam packets travelling regularly across the Atlantic was also vital in helping overcome isolation. Correspondents eagerly awaited the latest news and publications and just like today, the latest gossip!

-Kat-