31 July 2020

Kew in poetry

Take a poetic tour through the Gardens

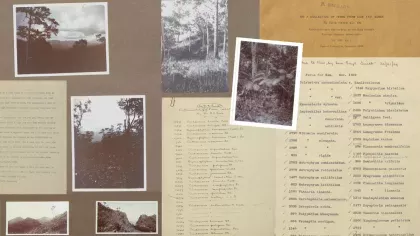

Kew Gardens is inspiring. There are a thousand ways our work has sparked creative projects in people across the globe. The Gardens in particular have proved an inspiration for poets, and the Library holds a fine collection of this work.

The collection contains an interesting mix of both big names and also amateur poetry. In some cases we chose to collect the items but in others, they were donated to us by former staff members, visitors, and Kew enthusiasts..

What treasures can be found within this collection? Here, we take a look and aim to share some of the highlights with you.

These are the words of a Darwin – not Charles Darwin, but rather his grandfather Erasmus; an acclaimed scientist in his own right. He was one of the leading voices of the Enlightenment in Britain and had already wrestled with the question of evolution to which his grandson would provide an answer.

He was widely educated, proactive, and published prolifically. As well as a scientist, he can just as easily be described as a physician, inventor, or as a philosopher. He fought for the abolition of the slave trade and the right of women to be educated at a time when these were still controversial ideas.

Most important of all however is the label of acclaimed poet. It wasn’t until Wordsworth and Coleridge burst onto the scene in 1798 that people stopped thinking of Erasmus Darwin as one of the premier poets of their time.

Making science popular

It is no surprise then, that the lines quoted above come to us from a run-away commercial success; one of the first ever popular science books to have been published in the English-speaking world - the appropriately titled The Botanic Garden (1791)

This book saw multiple editions and collected two long form poems together: The Economy of Vegetation (1791) and The Loves of the Plants (1789) which attempt to pack the latest scientific discoveries, theories, and issues into pleasant-to-read poetry.

This might strike you as odd – science and poetry seem to many people to live in entirely separate worlds – but this technique has actually been in use since the days of the Greeks and Romans.

Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things has a particularly nice image to explain it. He uses the analogy of coating bitter medicine (i.e. hard-to-read scientific knowledge) in honey (flowing poetry) to gently trick children (readers) into imbibing it. An image that still holds up after more than 2000 years.

Given the run-away success of Darwin’s book in getting people interested in botany, it seems only natural that William Jackson Hooker – Kew’s first official director - would use the lines to open his ever-green Kew Gardens Or, A Popular Guide to the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew which saw 16 editions from 1847-1858.

The first

You might imagine that the Erasmus Darwin poem was the earliest to try to capture the splendour of our Gardens in words – but you would be wrong. That particular crown goes to John Whaley and his poem simply titled 'Kew Gardens'. It came out in 1732 – just four years after what would become Kew Palace was first leased by Queen Caroline, the wife of George II.

The poem was discovered fortuitously by Chris Mills – former Head Librarian here at Kew – in a poetry book at an auction. It is the first of a long line of poetic outpourings inspired by the work the Horticulture and Science staff do here at Kew. If you would like to see them please contact our library staff.

Overall, the Library's poetry collection is a great starting point for an inspiring read and provides a fascinating insight into how Kew has been perceived at different points in history.