26 April 2019

What is botanical art?

Kew has never gone a day without an artist in our ranks. And modern-day science still relies on this ancient tradition.

Imagine being able to paint every part of a living thing with incredible, microscopic detail, with every flick of a brush bringing the vibrancy of a petal to life?

Botanical illustration does just that. It is one of the most specific, and vital artforms that plays a major part in botanical discovery.

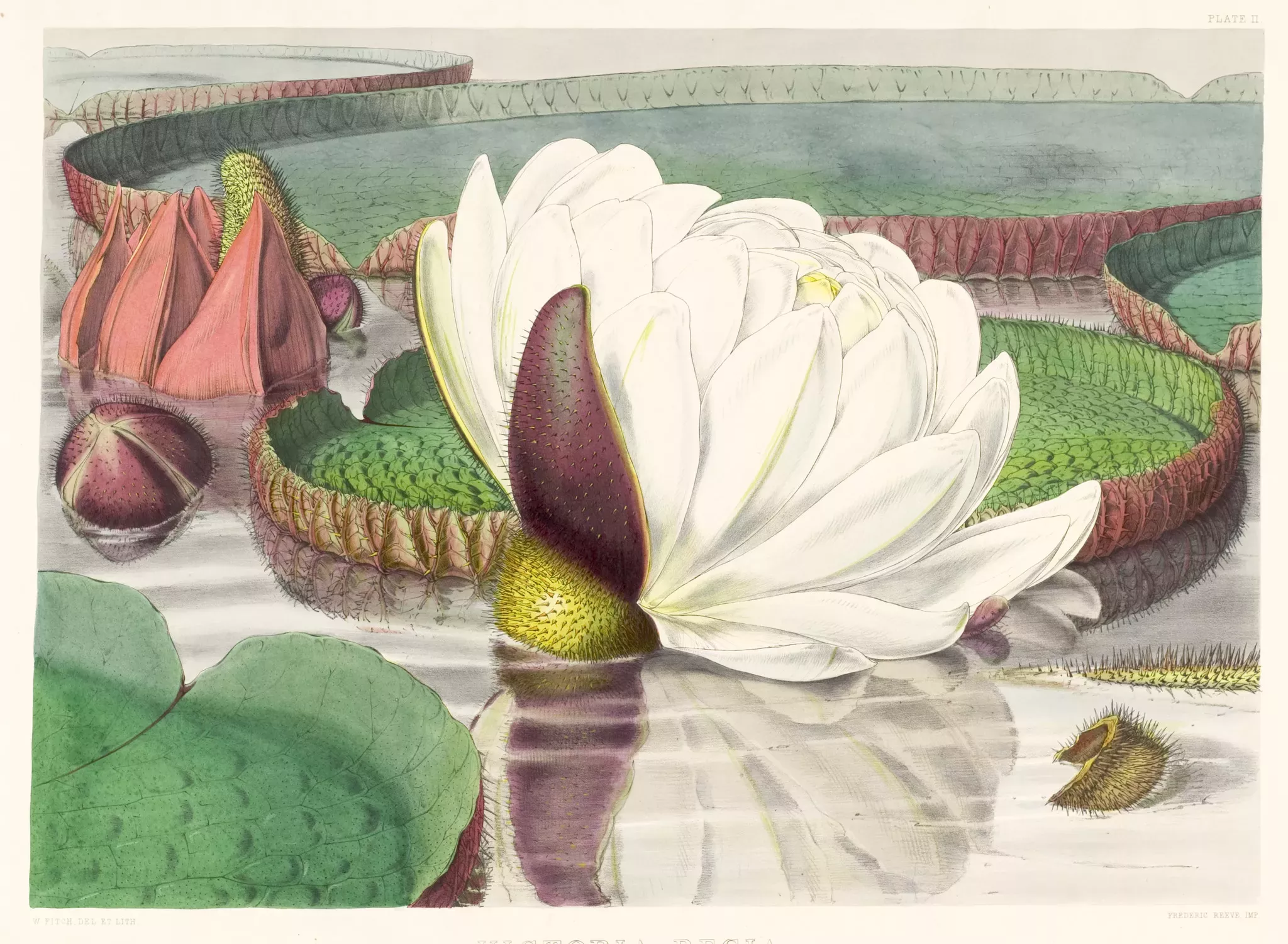

Every painting, or plate, that a trained botanical artist creates becomes the visual definition of its subject.

At Kew, this plate becomes cemented in history as part of our 200,000-strong botanical illustrative archive. This is a scientific tradition that dates back centuries.

In fact, Kew has never gone a day without a botanical artist in our ranks.

What is botanical art used for?

Right back to the early botanists, the artist was often the first to officially document many of the plants we know today.

An illustration is used to support the work of botanists and horticulturists, describing the plant for the science records.

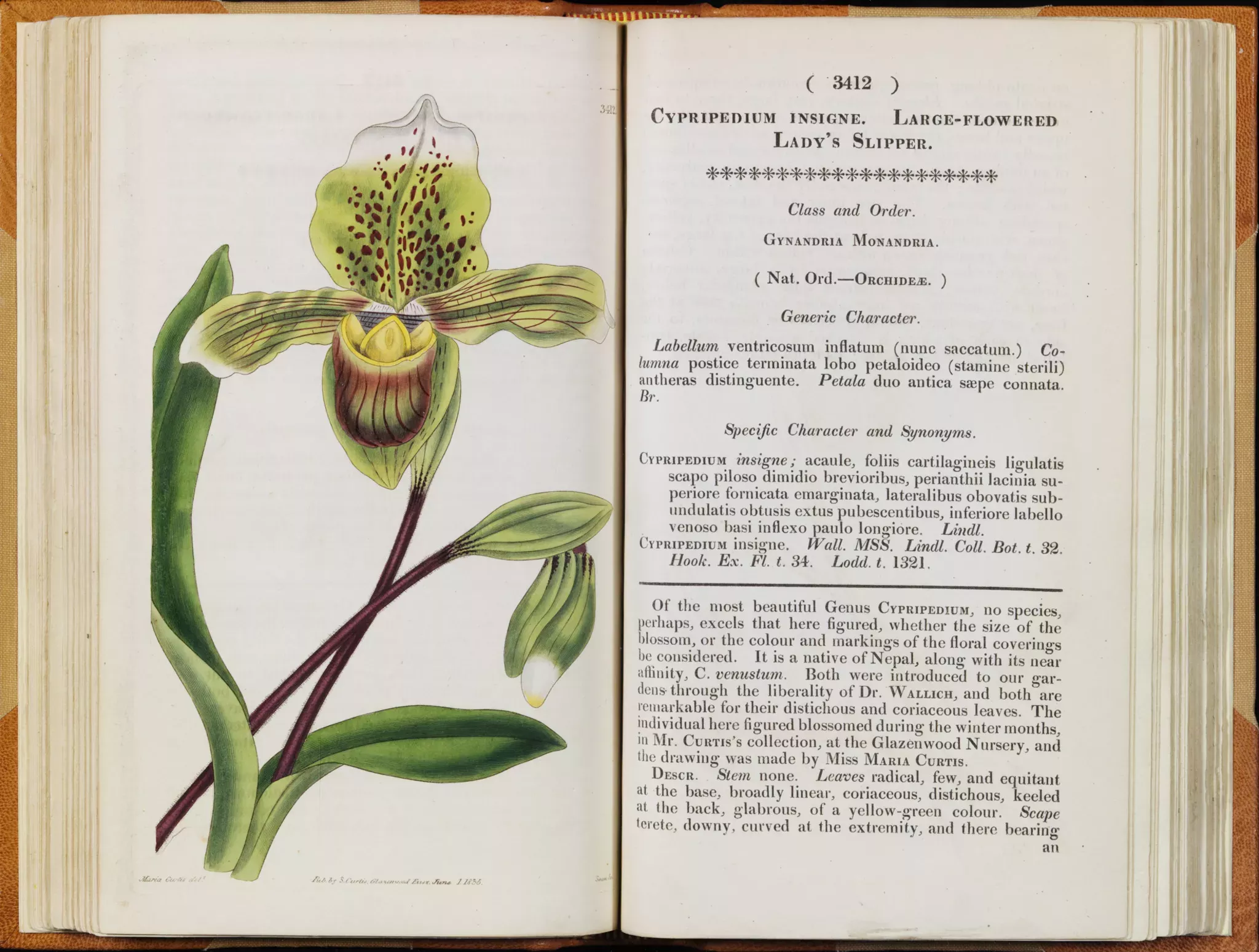

They appear in inventories, journals and field guides, but most importantly our artists’ plates are printed in the world’s longest running botanical magazine, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine – the definitive publication on botany and horticulture, and produced by Kew for over 200 years.

Published alongside a written description, the artist’s plate is part of the definition of a plant.

Maria Vorontsova, a taxonomist of Madagascan grasses, relies on botanical artists for her work.

‘Botanical artists are in fact scientific professionals. They help me identify grasses, which often have tiny spikelets and other small structures that I need to compare in order to understand what makes one grass different to another.

‘An illustration gives a better impression than my five pages of Latin text that goes alongside it! But it’s not just a communication tool, it is a scientific tool and absolutely essential.’

Famous artists

- Franz Bauer (1758-1840) – Viennese Bauer was Kew’s first botanical artist

- Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759-1840) – wildly popular botanical French artist working under Marie Antoinette

- Marianne North (1830-1890) – 833 of her remarkable paintings line our Marianne North Gallery

- Walter Hood Fitch (1871-1892) – the prolific painter of over 10,000 plates

- Margaret Mee (1909-1988) – specialist of Amazonian plants

- Christabel King – Kew’s current resident artist with a career spanning 40 years

Art is better than a photo

Photography and film may play a role in expeditions, but they can never replace the accuracy of an illustration.

Photography can’t bring each unique detail of a plant to life; whereas an artist can hone in on the way a leaf is attached to a stem, the formation of spikelets or hidden features beyond what’s in the photo.

Maria agrees, ‘On expeditions, I often take a drawing with me to identify what I’m looking at.’

Many early botanists were artists themselves, or hired an artist to accompany them in the field as sending the specimen back home risked damage or decay.

Today, we have the means to bring specimens back to Kew, where an artist has time and space to really inspect it.

The attention and care, often done under a microscope or camera lucida, can lead botanical artists to make discoveries of their own.

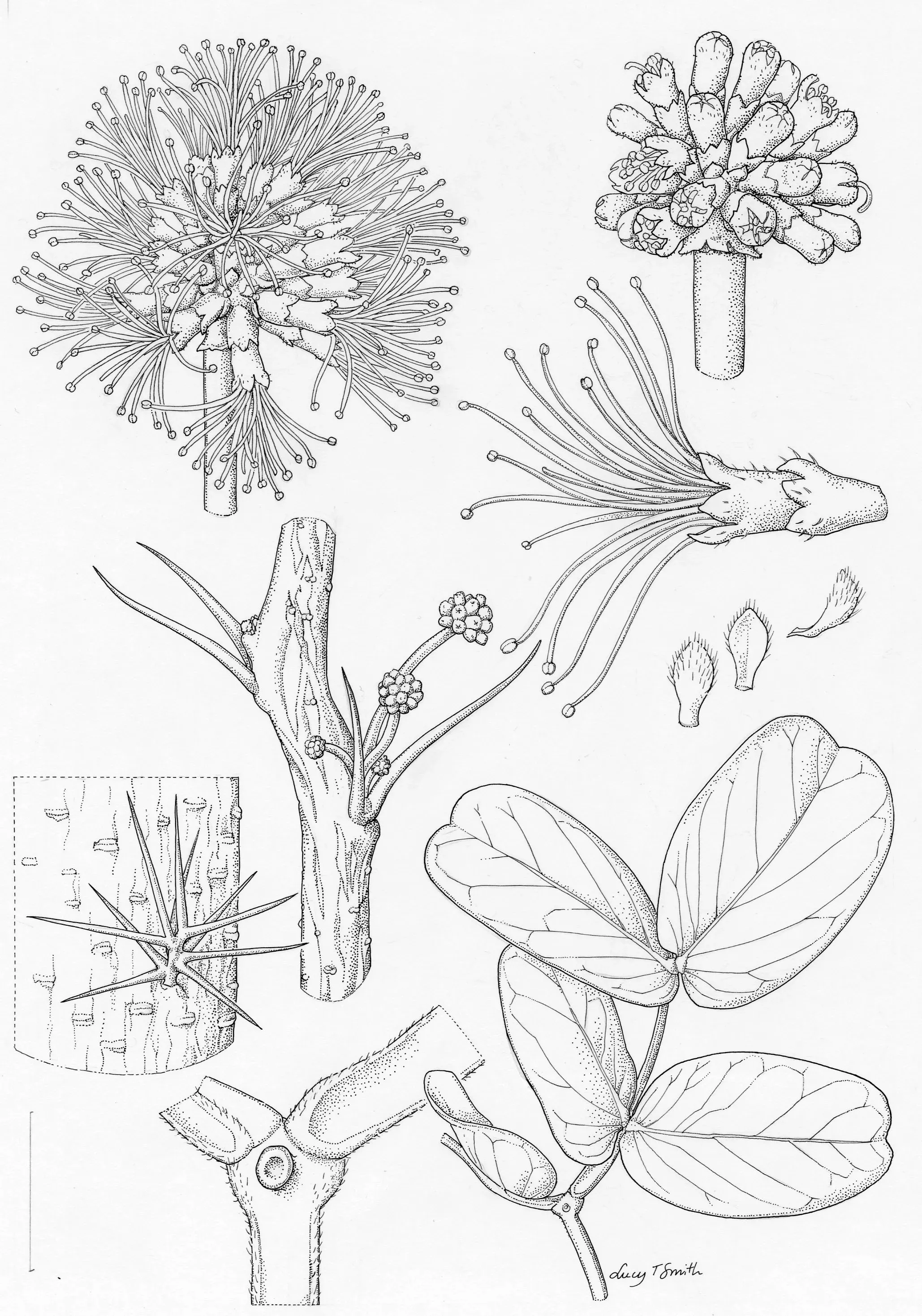

As artist Lucy Smith says, ‘Some things can’t be seen with a naked eye, so often I’m enlarging it 30 or 40 times the life size, and then painting it. I can be painting something of less than 2mm in size.’

How do you create botanical art?

The process of creating a plate is collaborative and scientific.

Together, the scientist and the artist go through a long discussion about the specimen, and which details are essential to bring out that will form part of the record, and a reference for other scientists.

The artist will decide whether to use pen and ink, or watercolour and their initial sketches.

Lucy says, ‘A specimen could come to us bent, folded or misshapen. It could be a dried Herbarium specimen, or in spirit alcohol. We have to bring it back to life, and recreate it in three dimensions so it looks like it’s alive again.’

Artists will either boil up or soak the material, pull it apart, or even dissect it with delicate care to see how the plant is put together.

They will measure the specimen to ensure the drawing is to scale, and inspect the colours to make sure their watercolour plate will be true to life.

The level of detail is remarkable.

Botanical knowledge is essential to this work, Lucy says, ‘Drawing is seeing. The minute you put pencil to paper, you are describing what you are seeing.

‘Every time we draw, we are making a judgement of the plant. An artist has quite a responsibility, and a natural curiosity. You want to find out more about what you are drawing. It’s about understanding botany, plant forms and every tiny detail.

‘Because, as artists, we are trying to show the absolute truth.’