21 February 2017

Walter Hood Fitch - an 'incomparable botanical artist'

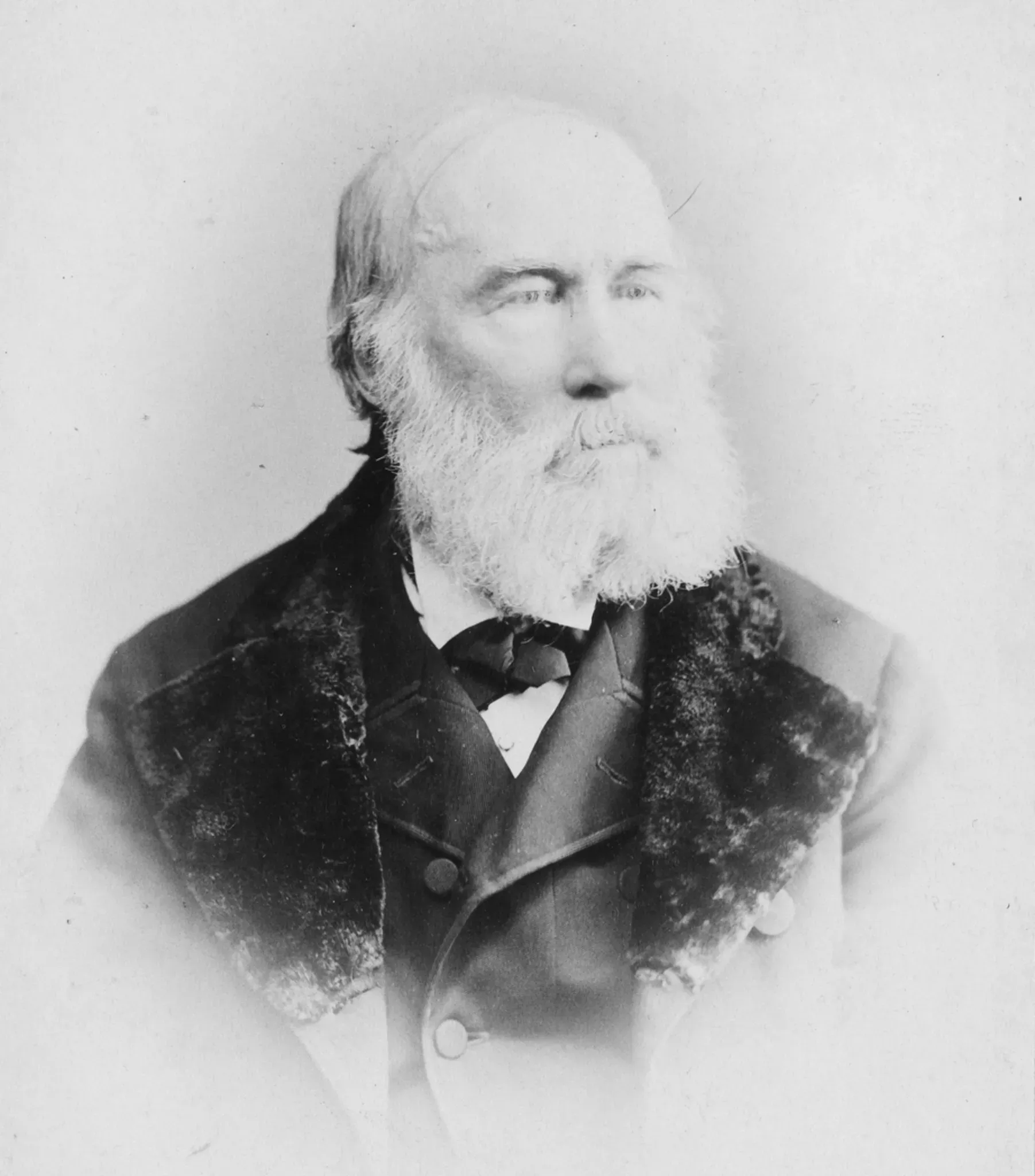

Lynn Parker looks at the story of Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892), one of the most talented botanical artists of the 19th century.

Fitch and William Hooker

2017 marks the bicentenary of the birth of Walter Hood Fitch, an artist little known outside the field of natural history illustration, yet he was probably the most prolific, and one of the most talented, botanical artists of the 19th century. His name is attached to almost every illustrated botanical or horticultural publication of significance published in Britain from the 1830s until the 1880s.

Born in Glasgow, Fitch was trained in drawing at an early age, and by the age of 13 was apprenticed as a pattern drawer at a mill. The mill’s owner, Henry Monteith recognised what an exceptional talent young Fitch possessed, and introduced him to his friend, the then Regis Professor of Botany at Glasgow University, William Hooker. Since 1826 Hooker had been editor of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, and was the journal’s sole illustrator, a considerable task for one man. Therefore when he saw Fitch’s work, he decided to take him on as illustrator on a trial basis, and soon began to appreciate the young man’s acumen for drawing and watercolour. Fitch’s first illustration for Curtis’s was a lithograph of Mimulus roseus published in 1834.

Fitch at Kew

In 1841 when William was appointed Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, he took Fitch with him and Fitch took up residence in Hooker’s new home, West Park. William relied heavily upon his friend’s assistance and company, and paid Fitch’s wages (which amounted to £100 a year) directly from his own resources. Now based at Kew, Fitch became the sole artist for the Magazine, as well as providing the majority of illustrations for official Kew publications over the next 40 years. Fitch would illustrate more than 2,700 plants for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, and published over 10,000 illustrations in total. He worked with William on his Icones Plantarum (1836–1876), and provided exquisitely detailed, life-sized illustrations for Hooker’s Description of Victoria regia (1847), a copy of which William presented to Queen Victoria.

Victoria regia (later renamed Victoria amazonica), was named in Queen Victoria’s honour. It had first been propagated from seed at Kew in 1849, but after several unsuccessful attempts, it failed to bloom. The flowering of this species was finally achieved by Joseph Paxton, gardener to the Duke of Devonshire, at Chatsworth in November 1849. The first bloom was presented to the Queen herself. Not quite defeated, William instead presented this lavish publication to the Queen, with illustrations by Fitch, depicting this magnificent 'Queen of the Waterlilies'.

Fitch and Joseph Hooker

Fitch collaborated with William’s son Joseph Dalton Hooker, contributing illustrations for his Botany of the Antarctic Voyage (1844-1859), Illustrations of Himalayan plants (1855), and his Himalayan Journals (1854). He also used Joseph’s field sketches to produce plates for the Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1848-1851). He possessed great proficiency in working from dried herbarium specimens to create expressive and accurate illustrations, a skill he was justifiably proud of, declaring, “…sketching living plants is merely a species of copying, but dried specimens test the artist’s abilities to the uttermost”; it was the basis upon which he believed he would “be judged a correct draftsman” (Fitch, Botanical Drawing, 1869). Joseph Hooker respected Fitch’s skill as an “incomparable Botanical Artist” (Hooker, J.D., Illustrations of Himalayan plants …, (1855), p.iv) whom he believed incapable of making “a mistake in his perspective and outline, not even if he tried” (Blunt, Great Flower Books (1990), p.47). Joseph Hooker named the genus Fitchia after the artist, as a mark of his esteem and gratitude.

Fitch’s skill as an artist enabled him to use Joseph’s elementary sketches and to work them up into detailed plates, as can be seen below. The hand-coloured lithograph by Fitch (shown beneath Hooker's sketch) appeared in Joseph Hooker’s Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya, 1849-1851 which was published while Joseph was still travelling in India.

Fitch's work after Kew

Despite working at Kew for more than 25 years, Fitch never held an official position at the institution, and in 1877 a dispute over pay ended Fitch's service to both the Botanical Magazine and Kew. However, Fitch’s talents continued to be sought after, and he remained an active botanical artist until 1888, contributing illustrations for Robert Warner’s Select Orchidaceous Plants (1862-1884), John Henry Elwes A Monograph of the Genus Lilium (1877-1880), and the Gardeners’ Chronicle, which continued to publish work by Fitch until 1893. When he finally succumbed to ill health, his merits were so well recognised as to gain him a Civil List pension on the recommendation of the Earl of Beaconsfield, of £100 a year. Walter Hood Fitch died on 14 January 1892, from a stroke. The day of his death coincided with the death of the Duke of Clarence, and the flag of St Anne’s church on Kew Green was flown at half mast, and the bell tolled all day. It was a coincidental but apt tribute to a man who had contributed so much to Kew during his lifetime. His obituary in the Gardeners’ Chronicle of 23 January 1892 declared that “as a botanical artist Fitch had no rival for grace and fidelity to Nature. His vast experience gave him a power of perception and insight such as few, if any, artists have possessed in greater, if equal degree.”

- Lynn Parker -

Assistant Illustrations Curator