9 November 2023

Venus flytrap: How does it work?

Everything you need to know about the carnivorous Venus flytrap, from how it catches its prey to growing and caring for your very own at home.

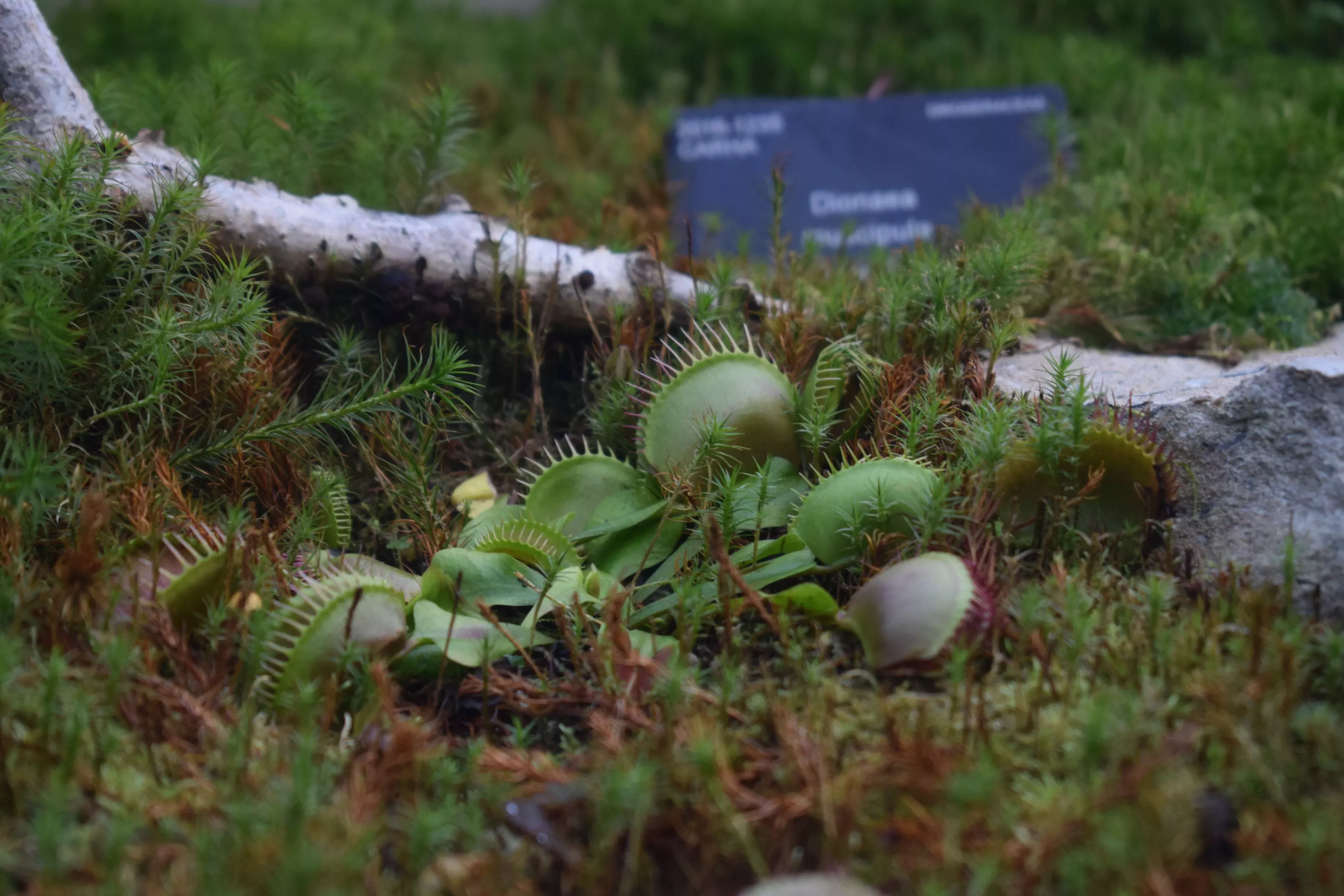

The Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) is a feisty carnivorous plant with jaw-like leaves that snap shut to trap and gobble-up insects and spiders.

Typically found growing in nutrient-poor soils, Venus flytraps rely on their elaborate snares for food.

Snapping traps

Insects are the main source of food for Venus flytraps.

They attract their prey using the reddish lining of their leaves.

On the inside of the leaf surface, there are tiny hairs. When touched, these hairs trigger the leaves to rapidly snap shut on the unsuspecting prey and the interlocking teeth lining the leaf seal the trap shut.

Once trapped, the leaves close tighter to squash the prey and enzymes are released that digest it.

The trap reopens around 10 days later once the insect has been digested.

Did you know? The Venus flytrap will only clamp its leaves shut if an insect trips its trigger hairs two times within about 20 seconds. This avoids wasting energy by closing unnecessarily.

Poached for profit

Venus flytraps are native to subtropical wetlands on the East Coast of the United States in North Carolina and South Carolina.

They are widely cultivated for sale, but their numbers are rapidly dwindling in the wild.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List classified the Venus flytrap as vulnerable - this is largely due to poaching.

This unique flesh-eating plant is highly desirable to poachers who steal them from the wild despite being widely available in the horticultural trade.

If poaching continues, Venus flytraps could go extinct.

Kew is helping to monitor and control the international trade of threatened wild plants, such as the Venus flytrap, to protect them from overexploitation.

You can do your bit by only buying Venus flytraps from properly accredited nurseries and suppliers.

Caring for carnivores

Venus flytraps have adapted over millions of years to thrive in incredibly specific environments, so they have a bit of a reputation for being fussy when kept as houseplants.

Here's a few simple tips and tricks you can follow to give your Venus flytrap the best chance of surviving at home:

- In the wild, Venus flytraps are found in acidic, nutrient-poor bogs; so at home, it’s best to grow them in acidic, water-holding soil that’s low in nutrients.

- To simulate the bogs they call home, it’s best to keep a potted Venus flytrap in a drip tray, and ensure the soil is kept damp and never dries out.

- Venus flytraps prefer acidic water, meaning a lot of tap water is too hard. Collect rainwater and use it to keep your flytrap happy.

- Keep your Venus flytrap in a bright, cool space, like next to a windowsill. During the winter, your flytrap might look like it has died. Don't be alarmed, it's actually in a dormant state and should return to life in spring if kept moist.

- It’s really important to not trigger the traps to close for no reason. A Venus flytrap uses a tremendous amount of energy to close its traps, so if it happens too many times your plant could die.

The world of flesh-eating plants at Kew

Our weird and wonderful carnivorous plant collection can be found in a dedicated zone in the Princess of Wales Conservatory.

Our Marianne North Gallery also houses a painting of ‘North American Carnivorous Plants’ by the remarkable botanical artist and plant hunter, Marianne North.