9 November 2022

From pods to puddings: Vanilla and other sweet-tasting orchids

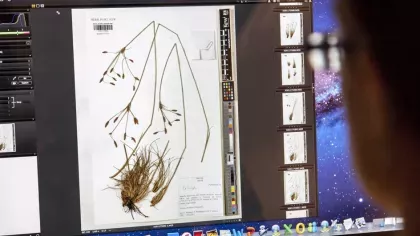

Kew’s Digitisation Team has been working with some of the sweetest and most fragrant orchids in our collection, soon to be made available online.

The Digitisation Team have been digitising Kew’s orchid collection since June 2022, having so far imaged and barcoded over 36,000 orchid specimens.

With the holiday season approaching, Christmas pudding topped with some rich vanilla custard seems to be on everyone’s mind.

In honour of British Pudding Day, we focus on some spicy and sweet orchids, but mainly the ‘vanilla orchids’.

Pods and puddings

The word pudding has an uncertain origin, with three possibilities:

- It either comes from the West German ‘pud’, meaning ‘to swell’;

- the French ‘boudin’, originally the Latin word ‘botellus’, meaning ‘small sausage’;

- or started as ‘poding’, coming from the Old English ‘pād’’, later giving origin to the Middle English ‘pod’, meaning ‘an outer garment, covering, coat, or cloak’.

All possibilities nod to the 13th-century origin of puddings, which originally consisted of meat, offal, suet, oatmeal, and seasonings encased by animal innards. But now pudding is mostly used to define a sweet dish eaten with a spoon instead of a fork.

Curiously, the origin of the word vanilla shares similarities with one of the possible origins of the word pudding. It derives from the Spanish ‘vainilla’ meaning 'little pod or sheath', in reference to the plant’s fruits (commercially called pods or beans).

Spicy orchids

Vanilla extract derives from the cured fruit pods of tropical climbing orchids of the genus Vanilla.

Currently, only two species, V. planifolia and V. pompona, and a hybrid, V. × tahitensis, are grown commercially worldwide. But species like V. cribbiana, V. insignis, and V. odorata are also locally grown for their fragrant pods.

Vanilla is not the only genus of orchids used in the preparation of desserts. The tuberous roots of Orchis mascula are ground to a powder and used for cooking. This powder has thickening properties and serves as the basis of the Arabic hot beverage salep and the Turkish mastic ice cream dondurma.

Elsewhere, the dried leaves of Jumellea fragrans are used to flavour rum on Reunion Island.

Selenipedium chica and Leptotes bicolor are also used as vanilla substitutes. While Leptotes bicolor is confirmed to produce vanillin (the compound that gives vanilla its signature flavour), the very rare Selenipedium chica is only known to be locally used in the Amazon region as a vanilla substitute.

Botanical silver: An agricultural nightmare

Growing vanilla is very challenging due to the plants’ ecological requirements, but especially due to their short-lived flowers and complex pollination.

In 1841, the 12-year-old enslaved Edmond Albius developed a simple and efficient artificial hand-pollination method that is still used today and allowed the spice to be introduced in Europe.

But vanilla remains the second-most expensive spice after saffron due to how labour-intensive growing the vanilla pods is. It currently costs £236.11 per kilo, around half the price of silver.

Vanilla only became an accessible spice during the 18th century with the invention of artificially produced vanillin.

Did you know? Vanilla is the most popular flavour in the world.

Sugar, spice, and everything nice

The 18th century marked the intersection between sweet puddings and vanilla when the spice became more frequently used in Europe, due to the introduction of artificial vanillin.

Vanilla was mostly seen as a chocolate additive until the early 17th century when Hugh Morgan, a creative apothecary in the employ of Queen Elizabeth I, created chocolate-free, vanilla-flavoured 'sweetmeats'.

By the 18th century, the French were using vanilla to flavour ice cream.

Simultaneously, at the end of the 18th century, the word pudding became mostly associated in the UK with sweet dishes. Many of these puddings were prepared using special pudding bags or cloths, the preparation method being the only remaining connection between savoury and sweet puddings.

Complex bouquets

As highlighted in our Halloween blog, the delicate and complex orchid flowers rarely retain their structure after being pressed and dried to become herbarium specimens.

Vanilla orchids tend to be especially delicate and have the tendency to dry from dark brown to black. The lip (the distinct-looking petal in orchid flowers) of many vanilla orchids has intricate ornamentations, including delicate folds and hairs.

For these reasons, illustrations are frequently included in or associated with herbarium specimens. These illustrations allow botanists to more easily analyse the specimens and provide our Digitisation Officers with a sneak peek into these flowers in real life. Despite their beauty, the illustrations can greatly increase the complexity and time necessary to digitise a single specimen.

The cherry on top

The digitisation of vanilla orchids and other ‘spicy orchids’ provide our team with an interesting opportunity to reflect on the importance of our job. Orchids are commonly thought of as ornamental plants, but Vanilla reminds us of their often overlooked potential and the importance of traditional knowledge.

Aside from acting as a virtual copy of the specimens housed at the Kew Herbarium, making this data widely and publicly available allows us to revisit our knowledge and understanding of our collection and the plants it holds.

We hope that, as we move forward, we continue to uncover exciting and unexpectedly sweet histories.

Hope you enjoy British Pudding Day with a rich serving of vanilla custard!