12 May 2023

To catch a tree killer – Plant Health Week

Louise Gathercole, a PhD student at Kew and Coordinator for the Centre for Forest Protection, shares her lifelong interest in plant health, and a research journey to understand a modern tree killer.

If you had told me ten years ago that in 2023 I would be working in plant health, I would have been confused.

Firstly, I did not know that plant health was a career area, and secondly, I hadn’t studied plants since GCSE biology. Also, and this is a very dangerous thing to confess on the Kew website, I am a useless gardener. I don’t so much have green thumbs as cursed thumbs and the main risk to any plant in my house or garden is me, rather than a pest or disease. How then, did I end up working in plant health?

In 2016 after a career break raising children, I went back to university to study a part-time science MSc. I learnt about how recent advances in genomics research are contributing to knowledge of human health and disease. Genomics is the study of the whole genome of an organism – the full sequence of DNA that makes each lifeform unique. It can include looking at the structure of the genome, interactions between genes and the environment, interactions between genes themselves, and differences between individuals.

As I read more about genomic methods, I discovered that a lot of the techniques had been developed originally for research into crops and their resistance to pests and diseases. This was where I first realised that plant health was an area of research that could be interesting.

A plant disease history

Although I am a terrible gardener, I have always been interested in nature and especially in woodlands and trees. One of my earliest memories of school was sitting on the large stump of a recently felled elm tree on the edge of our playground, crying my eyes out. Dutch Elm Disease was sweeping the country and the council had cut down the row of beautiful old elms in the school holidays, but nobody had told the children it was going to happen.

The trees had been part of our imaginative landscape – the homes of talking birds or magical creatures in our games – as well as providing us with shade and beauty. That single plant health issue has meant that subsequent generations have grown up in a landscape with very few mature elm, and it was an early lesson for me that trees can get sick too.

Sick trees came back into my life when I started my PhD in 2019, at Kew and Queen Mary University London, and began to learn about acute oak decline.

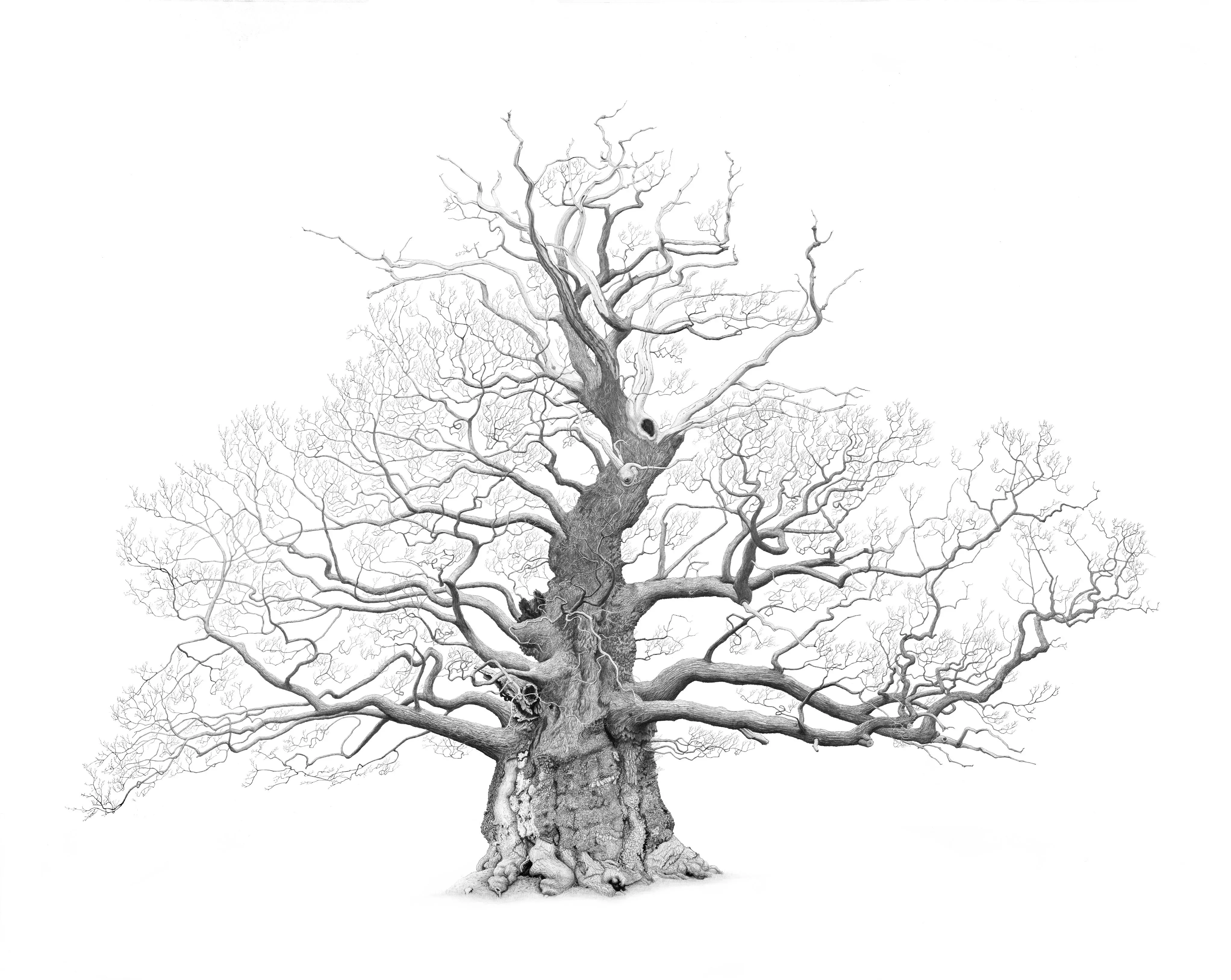

Oak trees are some of the most familiar sights in the British countryside, found in woodlands, wood pasture, parks, village greens, and fields. We have two native species - the pedunculate oak and the sessile oak, although there are hundreds of other species around the world. Oaks are very long-lived trees and provide an incredibly important habitat for many other organisms. This habitat changes with the age of the tree, with veteran oaks providing a home for many species that would take several hundred years to replace.

Alongside their ecological importance, oaks are a key timber crop, providing sustainable materials for building, furniture and other items. They are also an important visual part of the landscape and have historical symbolic meanings in cultures around the world.

A complex problem

Like many other tree species, oaks are under increasing threats from invasive species such as oak processionary moth and mildew. Pollution can change the chemical balance of soils and leaves and climate change may mean that oaks are more susceptible to certain diseases.

Acute oak decline is a disease that has been observed and monitored in Britain over the last 15 years and several groups of researchers have been discovering more about its causes over that time.

The disease is usually visible in the trunk of the tree where there are vertical cracks in the bark, often oozing a dark fluid. These cracks sit on top of rotten parts of the sapwood underneath, where big holes or lesions can be seen. Within the lesions are often found the larvae of the two spotted buprestid beetle Agrilus biguttatus, which is native to the UK. On some trees, it is possible to see D-shaped exit holes where the adult beetles have emerged.

The lesions seem to be caused by a group of bacteria that are new to science. They have the ability to break down the cells in the wood and seem to work together in a way that we don’t fully understand yet. The presence of the beetle larvae seems to supercharge the bacteria’s activity, and then the larvae make things worse by boring ‘galleries’ in the wood.

Over time, these lesions and galleries can prevent water, nutrients and the sugars from photosynthesis travelling up and down the trunk. The crown of the tree can start to die back, and some trees die within five years. Other individuals manage to grow new wood over the lesions and go into a state of remission, but they can be affected again in the future.

Exploring a bacterial mystery

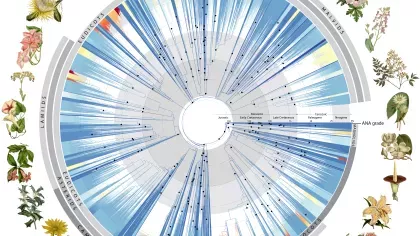

At Kew, we have been working with Forest Research to collect leaf samples from monitored sites across the country, and extract their DNA for whole genome sequencing. When you extract DNA from a leaf, you don’t just get the DNA of the tree, you also get DNA from anything living on or in the leaf.

By studying the DNA sequences that don’t map to the oak genome, I’ve confirmed the presence of these lesion-creating bacteria in the leaves of both healthy and sick oak trees without causing any harm.

Even more curiously, I’ve found the bacteria in sites where no trees are suffering from acute oak decline at all. This suggests that there is more going on than a simple infection by a pathogenic bacteria in this particular tree disease and it is possible that the bacteria are a normal part of the woodland microbiome.

Researchers from the Future Oak project are now taking swabs from leaves and growing the bacteria in a lab to see what they can find. They are also looking into whether other types of bacteria can protect trees from the problem bacteria.

We do know that environmental factors play a role in making trees more susceptible to acute oak decline and that some sites are more likely to have sick trees than others…

What we don’t yet know is why some healthy trees never get sick despite living in the same woodland as sick trees, or why some trees are able to recover for a while.

Healthcare for oaks

At Kew, we have continued to work with Forest Research to collect and sequence samples so that we have a big enough collection of them to carry out something called a ‘genome-wide association study’ which aims to find out if there are differences in the genome between trees that are susceptible to disease and those that are resistant.

It is possible that acute oak decline is entirely down to environmental factors, but if we can identify individuals that are genetically more resistant, we can use that information to select trees for future planting programmes.

The collaboration Kew has with Forest Research has now grown into the ‘Centre for Forest Protection’, The centre uses interdisciplinary and innovative methods focused on the future of tree and woodland health, researching tree health issues ranging from environmental risk modelling to testing which native beetles might be capable of carrying a disease between pine trees.

In October, alongside my research on oak trees, I started work as the Coordinator for the Centre for Forest Protection. This means that I now get to work with scientists and stakeholders on a range of tree health issues, which is incredibly interesting and varied. A career in plant health is not something that I expected to find myself switching to in mid-life, but it is really important work and I am very glad that I found it.

-

Tree Alert

If you spot a tree health issue, you can report it to the Tree Alert project.

-

-

Centre for Forest Protection

More about the latest partnership studying the intricacies of plant health