The murder of Dr Charles Budd Robinson

The death of enthusiastic plant hunter Dr Charles Budd Robinson in Ambon, as told by the murder report in Kew's archives, and learn why miscommunication can be deadly

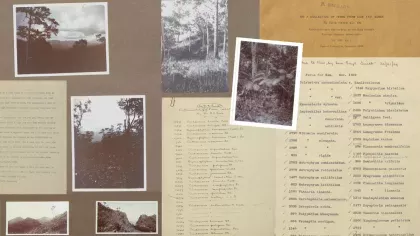

It is not often that, on reading through the , we come across a murder report. Yet this is exactly what we uncovered recently when digitising a volume of letters from the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia in the early 1900s. The story is a tragic one and serves as a reminder of the conflicts that arose as a result of European colonialism and striking cultural clashes.

Dr C B Robinson

Charles Budd Robinson was born in Nova Scotia in 1871 and briefly worked at the New York Botanical Garden before joining the Bureau of Science in the Philippines. In 1913, Dr Robinson embarked upon a botanical exploration of the island of Amboina (now Ambon), in Indonesia, with great enthusiasm and was well liked among both the European and native inhabitants of the island, which made his murder especially shocking as it was so unexpected. The report in Kew's archives is a copy of one made by the Assistant Resident of Amboina, Mr van Dissel, to the Resident of Amboina, Mr Raedt van Oldenbarnevelt. From here, I will rely on extracts from van Dissel's report to tell the sorry tale.

Dr Robinson was reported missing on 11 December 1913, having left on a botanical excursion six days earlier. 'The general impression was that there had been an accident, because Dr Robinson, as a botanist, was in the habit of frequenting the most remote places'. It was a few more days before the truth behind his disappearance finally emerged and van Dissel pieced it together as best he could.

Dr Robinson arrived at a remote settlement where 'A young Boetenese...who had climbed up a coconut tree to get a few coconuts...saw Dr Robinson standing at the foot of the tree' and became frightened – unused to seeing a European in such a remote place. He hurried home and 'here he caused much excitement among the people by telling them that he was being pursued by a European. Dr Robinson, who followed the boy, then arrived at the settlement and asked for a drink...whereupon a woman handed him a glass of water.'

Some confusion then arises as to the exact cause of the murder, but statements made by the boy caused the investigators to deduce that 'the people were in fear and trembling that Dr Robinson would do them some harm, on account of rumours which regularly make the rounds of the Moluccas in the months of November and December'. These rumours related to the ritual of head-hunting, which was previously observed in some regions of Indonesia and known as 'potong kapala' (literally: to chop someone's head off), which left people afraid of certain persons or 'creatures' seeking to decapitate them. Possibly, poor Robinson was taken to be one of these malevolent persons.

Extract taken from the obituary of Charles Budd Robinson

'The headman of the settlement followed Dr Robinson, armed with an axe, and said to one of his countrymen: "There goes a dangerous European who wants to cut off our heads; I am going to kill him," ' – and he did, with the help of five others. 'The body, with everything found on it, was wrapped in coconut leaves, weighted with stones, and sunk in the sea'. Van Dissel goes on to assert that 'This misfortune would never have happened to Dr Robinson had he not started out unaccompanied...Moreover, I can imagine how natives living in remote regions...and already unreasonably afraid of Europeans, should be much frightened by the aspect of Dr Robinson...who dressed in khaki cloth, with a queer small felt hat on his head and carrying a kind of hunting knife, looked quite different from any of the Europeans one sees hereabouts'. Even in Ambon City, the locals said he looked like a convict.

Another embellishment of this story is that Dr Robinson actually asked the boy to cut him down a coconut. Regrettably, the Malay word for coconut, 'kelapa', is decidedly similar to the word for head, 'kepala', and so Dr Robinson, with his poor knowledge of Malay, may actually have asked to cut off the boy's head. Whatever the true reason, superstition and fear took over and Dr Robinson was sadly killed. His death came as something as a shock to the relatively safe country, and was keenly felt by the whole of Ambon as he had gained the affection of the entire community. He was amiable and well known by the locals who referred to him as 'Dr Kembang' – the flower doctor.

Dr. Robinson was an amiable person. According to the children of Ambon, who brought him specimens for his herbarium and to whom he was always so kind and friendly, he was incapable of doing any harm. His death has coused general compassion among the poulation of Ambon.

Extract taken from a copy of Mr Raedt van Oldenbarnevelt's letter to the Governor General of the Dutch East Indies

The final word goes to Resident Mr Raedt van Oldenbarnevelt, who, in a letter to the Governor General of the Dutch Indies, reminds us of the perils of miscommunication when he writes that Robinson 'had taken a great liking to the population, as they were always very kind and accommodating towards him on his many excursions through the interior of Ambon...Although I myself had frequently advised him not to go out alone...because he spoke Malay so poorly.'

- Charlotte -