1 March 2019

The Artist Plantsman

Inspired by the artist John Nash, Library Graduate Trainee Will McGuire explores Pasqueflowers, landscape, and history.

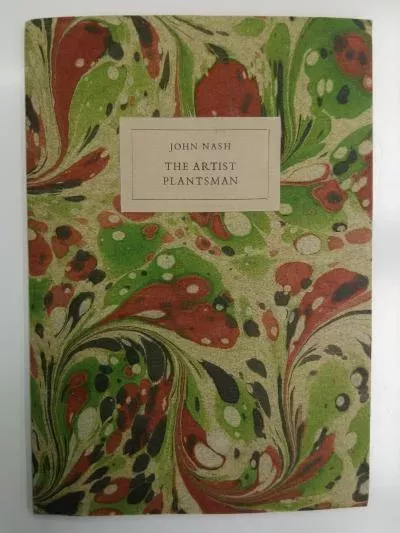

The Artist Plantsman by John Nash is a small, thin book wrapped in red and green marbled paper. It is a brief account of an artist’s relationship with nature; in this post, I’ll try to follow (in a loose way) some of the threads suggested by the book. John Nash, who lived from 1893 to 1977, was a painter, illustrator, engraver, keen gardener, and brother to Paul Nash, also an artist; both are known for their landscape paintings, but each brother painted landscape differently – “Paul with his head where a poet’s should be, in the clouds, and John like the child the painter should be, putting his brush in his mouth to tell us what he has seen in the field or on the farm that afternoon,” wrote the artist Walter Sickert. This may be too simple a differentiation, but John Nash’s love for the plants and the countryside certainly informs his work – most obviously in his botanical illustrations, but also in his more general care for and attention to nature. Wilfrid Blunt, author of The Art of Botanical Illustration, describes it as - rather than drawing a flower, John Nash drew a particular flower: a portrait.

Poisonous Plants

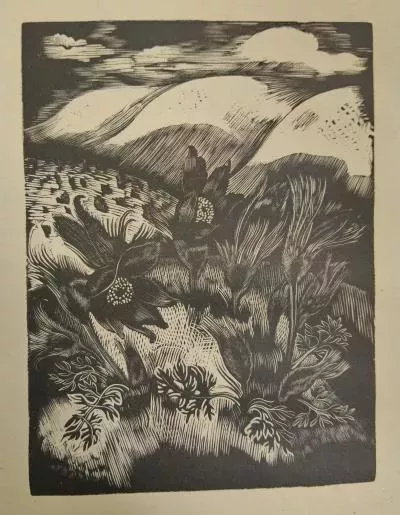

In 1927, John Nash was asked to illustrate the book Poisonous Plants by William Dallimore (he also ended up writing the introduction after, allegedly, a certain Director of Kew failed to supply one!). Wood engraving is not a technique favoured by most botanical illustrators, but John Nash makes it work against the odds. Plants and landscapes emerge from thin lines on deep black printing. “Nothing lush in his work, rather otherwise, as if the flesh had been picked off and one was left with the bare bones of the landscape,” John Lewis writes in John Nash: the painter as illustrator. Even if John Nash was not as visibly preoccupied by war and trauma as Paul Nash, there is still something haunting in some of his paintings, etchings and drawings – and Poisonous Plants is a good place to start. A personal favourite is the illustration for Pasqueflower, an interesting plant in its own right, and one which seems in John Nash’s engraving to be overwhelming the landscape from the foreground backwards.

Pasqueflower: blood and barrows

In British folklore, Pasqueflowers appear where the blood of Danes and Romans was shed, the silky purple flowers colouring barrows and boundary banks. Well-located ancient sites can provide an undisturbed habitat for Pasqueflowers, which favour chalk and limestone grassland. These grasslands are a precious home to many wild flowers, plants and insects. Often, they were once forested, and would have been cleared by early human inhabitants - perhaps to build burial mounds or ‘barrows.’ Now, the curved expanses of these landscapes can seem emptied of people, but, as in the Seven Barrows site on the Berkshire Downs, for a long time it was the rolling form of the barrows that kept away the plough and the farm; the barrow-makers are still with us. (Paul Nash’s painting 'Equivalents for the Megaliths,' from 1935, coincides to some extent with this thought, drawing out the similarities between standing stones, hay bales and abstract sculpture).

Pasqueflower: resurrection

Purple dashes of Pasqueflowers on historic sites could be a reminder of these older presences; like megaliths, equivalents for long-ago histories. Pasqueflowers flower in spring, around Eastertime, and the name Pasqueflower itself comes from the archaic French for Easter, Pasque; a time, in the Christian tradition, associated with resurrection and with the Passion of Christ (and so, possibly, with blood); and a time, in the northern hemisphere at least, associated with celebrations of life brought to the surface by the new warmth of spring. Across its range, Pasqueflower’s early-spring flowering is attached different significances. In South Dakota, where they are the state flower, Pasqueflowers bloom in early May, and they are some of the first wild flowers of the year to do so. There is a Dakota Sioux song for the twin-flower or Pasqueflower:

I wish to encourage the children

Of other flower nations now appearing

All over the face of the earth;

So while they awake from sleeping

And come up from the heart of the earth

I am standing here old and gray-headed.

Call and response

The twin-flower’s song calls other flowers to rise from the winter chill. (The song was translated from the Dakota language by Dr. A. McG. Beade and published in Melvin Randolph Gilmore’s Uses of plants by Indians of the Missouri River Region, revised edition published 1991. It can also be found on Kathleen Keeler’s blog post about Pasqueflower – link below). The idea of flowering by a kind of call-and-response suggests an interesting idea of ecology. It is also suggestive of the way in which books and other texts can work, each in turn suggesting others; stories, illustrations, histories and songs with unexpected connections.