23 November 2019

A quest to conserve willow seeds

As part of the UK National Tree Seed Bank Project, willow seeds have been collected from across the UK for future conservation and research.

From medicines to basketry and sports equipment, willows (Salix sp.) are an economically and culturally important plant family.

Reports of willow bark being used as a treatment for aches and pains date back to the Egyptians. However it wasn’t until the 19th century that the active ingredient salicylic acid was isolated from the bark – a synthetic derivative of this compound is nowadays known as aspirin.

The shock absorbing properties of willow wood, specifically from the cricket bat willow, Salix alba var caerula make it perfect for cricket bats, while the supple nature of osier shoots (typically S. viminalis, S. pentandra and S. purpurea) makes them a popular choice for basketry and weaving.

Not forgetting its powers when made into a wand, with Ron Weasley's second wand being made of willow wood.

An insurance policy

There are approximately 14 species of willow considered native within the UK, from the rare Salix lanata of the Scottish Highlands, to the common Salix caprea. They vary in growth form from small creeping shrubs barely reaching 50cm high, to towering trees tens of metres tall.

As part of Phase 2 (2018-2020) of the UK National Tree Seed Project, we set out to trial seed collecting for four relatively common native species – Salix aurita, S. caprea, S. atrocinerea and S. repens. Although these four willow species aren’t currently under any known or immediate threats, we don’t know what the future holds.

Over recent decades there has been a dramatic increase in the number of novel pests and diseases attacking trees in the UK, such as ash dieback.

Add to that changing temperatures and more extreme weather events and our woodlands are subject to multiple risks. But collecting and banking willow seeds is particularly tricky.

How do you identify a willow tree?

In the field, plant identification is usually based on visible characteristics of the plant such as its growth form, leaves, twigs, catkins and flowers.

But willow species regularly hybridise with each other, creating individuals with a range of characteristics between the two parent species, making it difficult to identify which are hybrids and which are true.

Willows are also renowned for having wide variation in characteristics such as leaf shape, depending upon the environmental conditions in which plants are growing which also makes identification tricky.

And, just to add in another layer of complexity, ideally you need adult leaves along with male and female catkins for definitive identification, yet in many species (including those on our target list), the adult leaves don’t develop until after the catkins have fallen and the seed has dispersed.

Further to this willows are dioecious, meaning plants are either male or female, so even after you’ve found and identified a plant, it may not be female (so not produce seed), or there may not be a male of the same species within the area increasing the chance that any seed produced could be hybrid.

Fluffy seeds

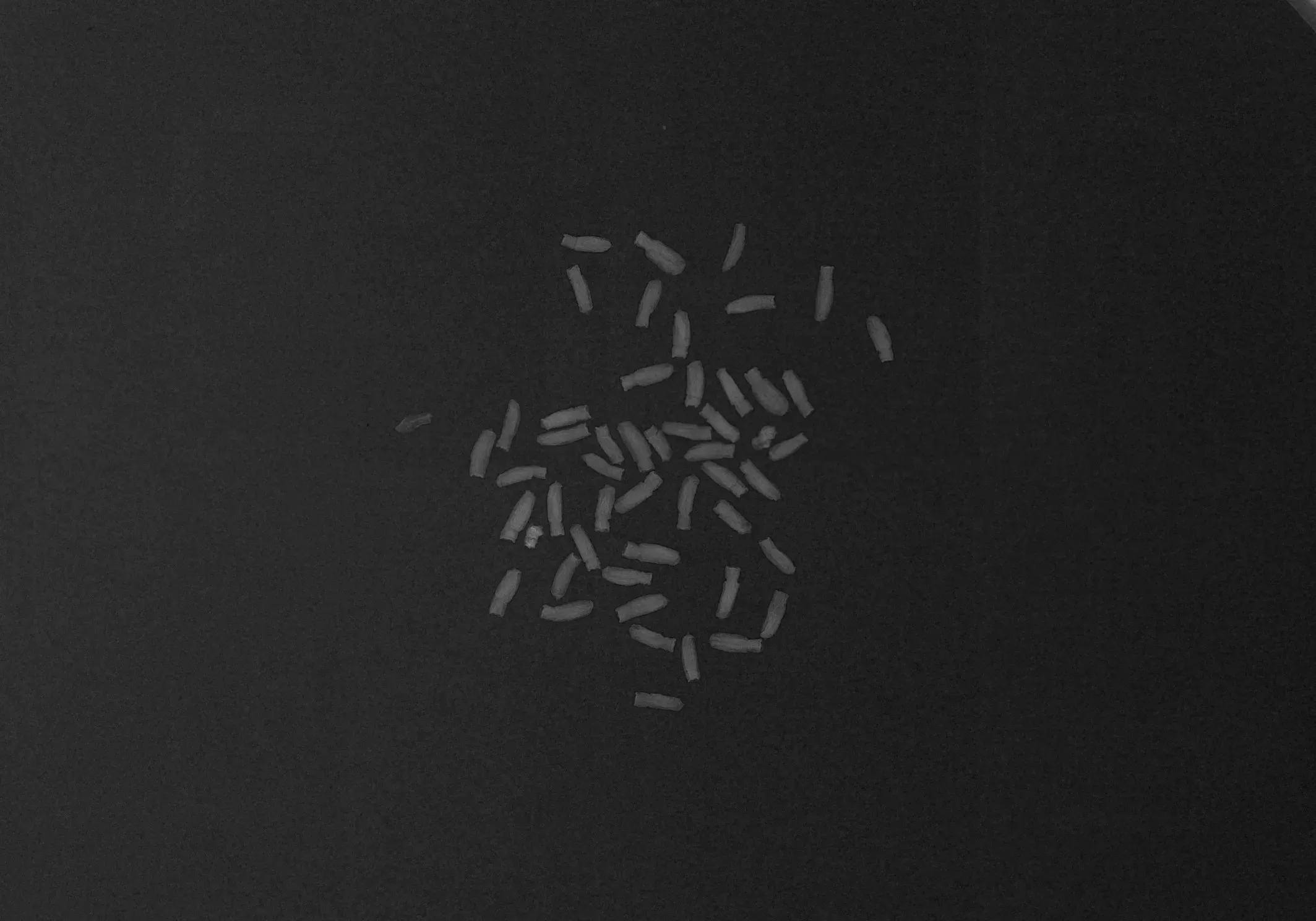

Willow seeds are relatively small, averaging just a couple of millimetres in length and are very effectively dispersed by the wind thanks to the fluff attached to each seed.

On a warm sunny day even under a gentle breeze the seeds float away. This makes timing a seed collection a little problematic.

Not to mention trying to collect them in the rain - think trying to separate cotton wool in a rainstorm and putting it into a paper bag.

Blink and you’ll miss it

Willow seeds have no endosperm (the nutrient part of the seed), and for many species, including those on our target list, under natural situations, germinate as soon as they land on a suitable site.

Consequently, they have no dormancy mechanism to delay germination and tend to lose viability very quickly once released from the maternal plant if they don’t land on a site suitable for germination.

In practical terms for seed banking, this means that we have a very short window of time to get the seeds from the plant to the seed bank, typically a week although ideally within three days. And the seeds then need to be processed and banked within two weeks of arriving at the Millennium Seed Bank.

Test and seek

Bearing in mind these challenges and after making a few test collections, experimenting with storage conditions alongside gathering knowledge from the scientific literature, we established a protocol for trialling large scale banking of willow seeds.

Most of the seed collecting for the UKNTSP is done by partner organisations and their volunteers across the UK.

Over the last two years we have received 76 collections of willows seeds from all over the UK, from the Outer Hebrides to Devon. We’ve even been to Ashdown Forest in Sussex, aka Hundred Acre Wood, the home of Winnie the Pooh.

With an average arrival time of just 2.75 days from the point of collection, this is a fantastic result due to all our partners hard work.

It took teams here at the Millennium Seed Bank over 254 hours to clean all the Salix collections, a careful process involving drying out the damp collections before vacuuming them through a series of different sized sieves, removing the fluff from the little seeds.

Banked

The seeds themselves have now all been processed and are stored in our Millennium Seed Bank, providing a resource for future generations.

We’ve also been undertaking more testing too and will continue to monitor the collections into the future. This will generate data that will allow us to revise and improve our protocols for processing/ curating and storing Salix seeds in the future.

References

Montinari, M.R., Minelli, S. & De Caterina, R. (2019). The first 3500 years of aspirin history from its roots – A concise summary. Vascular Pharmacology, 113: 1-8.

Acknowledgments

The UK National Tree project is funded by players of the People's Postcode Lottery.