26 October 2018

Passionate pioneers: increasing access to botanical artwork by women artists

With the help of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Virginia, USA, Kew has embarked on a project to digitise hundreds of works by women botanical artists.

Why digitise?

Historically, women botanical artists were rarely given as much credit as their male counterparts. To help tackle this issue, Kew’s Library, Art and Archives department is working in collaboration with the Oak Spring Garden Foundation to digitise out of copyright work by women artists from the collection, spanning several centuries.

Kew holds over 200,000 prints and drawings, and this working resource is available to staff and visitors to the department, often providing a reference tool against preserved herbarium specimens. The ultimate aim of this collaborative effort is to ensure that high quality images of illustrations and the associated data is safely stored in digital format for future generations.

The benefits of this process are threefold. We are improving access to our unique collections (the images and data will be available online), we are preventing any potential loss of information (if the worst happened and the collections were somehow lost or damaged), and we are extracting and collating artwork that is currently being stored with specimens in the herbarium. This artwork is also being rehoused in more appropriate storage conditions as we go along – another bonus!

Think of it as a huge inventory, with photography, data transcription and then the upload of digital files to nicely wrap it all up.

Botanical pioneers

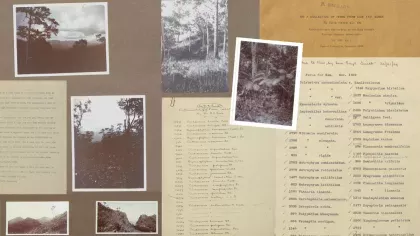

There seems to be a pattern that emerges when you start to research botanical artwork created by women, particularly those who lived and worked in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. “Very little is known about her”… “She published her work anonymously”… or, very commonly, was only known by her husband’s name. “Mrs T. R. R. Stebbing” on an acquisition label is actually referring to the early 20th century botanical artist Mary Anne Stebbing, and these mismatches can make initial research extremely difficult! There are even cases of some of these works not being signed at all.

Though often unrecognised, these artists made a huge impact on our current understanding of botany. From the anatomical structure of plants to the habitats in which they grew and the communities that relied on them, women artists were real trailblazers in their field. Probably the most well-known example is Marianne North (1830–1890), the intrepid explorer, biologist and botanical artist. However, one interesting example of an artist of whom very little is known is Sarah Anne Drake (1803–1857), or “Miss Drake”, as she often signed her work.

Sarah Anne Drake

Born in Norfolk, Sarah Anne Drake moved to London in around 1830. Through a family friendship, she was brought into the household (possibly to act as a children’s governess) of John Lindley, the then secretary of the Horticultural Society of London and a keen botanist. Lindley soon recognised that Drake was an extremely talented artist, and within a few years she had been commissioned to illustrate Lindley’s famous publication Sertum Orchidaceum (1837–1841).

The 19th century saw an explosion of interest in orchids (one might even describe it as an obsession). Scientists were keen to illustrate these incredible and exotic plants to accompany their publications, and Sertum Orchidaceum was indeed a lavish example of this botanical craze. But as well as orchids, Drake also provided highly technical illustrations for a number of other publications of the time, including the wonderfully titled Ladies Botany (1834–1837) and The Botanical Register (1815–1847).

Drake died in 1857, back at her home in Norfolk. As well as producing an extensive amount of botanical illustrations for highly popular publications, she was posthumously remembered in the Australian genus of orchid named for her, Drakaea.

The Ann Lee collection

An even more enigmatic artist whose work is held at Kew is Ann Lee (1753–1790). Ann’s father, James, was a nurseryman in London who supplied exotic plants to Kew. The 'Ann Lee collection' at Kew includes over 150 works, mainly watercolours, donated to Kew in 1969. Some of the works are signed and dated by Ann herself, and have a distinct style suggesting that they were indeed painted by one person.

However, around 60 of the paintings in the collection are unsigned, undated and were in a very poor condition before they were recently conserved. It is thought that these charming paintings, many of which feature insects as well as plants, were painted by unknown Chinese artists and were collected by James Lee, possibly as examples of exotic plants.

Sadly, the provenance of these works may never be discovered, proving once again how vital the task of digitising them can be. Maybe someone who reads this, or who happens to be browsing through these collections when they are soon published online, can help us to shed some light on the skilled but sadly uncredited artists that produced them.