20 April 2018

New classification of tropical forests

Kew Research Associate Jon Lovett describes the recent findings of an important study which has led scientists to ponder the evolutionary history of tropical forests.

Kew collaboration

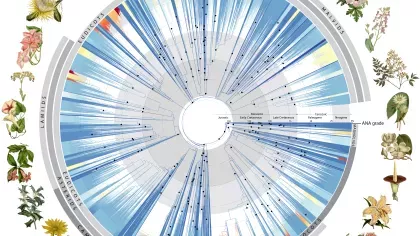

Kew is part of an international collaboration that has produced the first classification of the world’s tropical forests based on the similarity of their long term evolutionary history. This helps us to understand the living history of the Earth and provides pointers for conservation management.

Old World and New World

The classical way of dividing tropical forests is into the ‘Old World’ of Africa and Asia, and the ‘New World’ of South America. This division goes back to antiquity, but the text books will need to be rewritten following a remarkable analysis carried out at the University of Brunei Darussalam in Borneo that paints a radically different picture. The study used information from 439 locations across the tropics containing 925,009 individual trees belonging to 15,012 taxa to compare how the samples of trees were genetically related to each other. It was discovered that the forests of Africa and South America are more closely related to each other than to those of the Indo-Pacific, showing how tropical plants evolved as the Earth’s continents separated more than 100 million years ago under the forces of plate tectonics.

Asia in Africa

However, the classification is not clear cut. Some forests in eastern Africa are related to those from the Indo-Pacific. The extraordinary species rich forests of eastern Tanzania and south-east Kenya are full of rare plant species known only from this small mountain area. Similarities between these forests and those in the Indo-Pacific indicate that there are ancient links that could be very old indeed, as India and Madagascar were once joined to Africa as part of the Gondwana super-continent that broke apart about 120 million years ago.

An example is the rare tree Neohemsleya usambarensis. First discovered in the 1950s by Kew botanist J. H. Hemsley in the high mountain forests of the West Usambara mountains of Tanzania, it remained too poorly known to describe until rediscovered by Roger Polhill, Chris Ruffo and myself on a Kew expedition in 1983. It goes by the local name ‘Mkesse’ in Kisambaa and it’s used locally to treat toothache. There is only one species in the genus and it is only known from these mountains, but it’s nearest relative is in Asia rather than Africa!

Global dry forest region

Another remarkable finding from the study is that there appears to be a global dry forest region common to South America, Africa, Madagascar and India. This link is illustrated by the African Blackwood tree, Dalbergia melanoxylon, which is harvested in Africa to make musical instruments such as clarinets. It is also known from India.

Traces of the Boreotropics

The study also reveals that probable remnants of once extensive ancient lush tropical forests that covered the northern hemisphere, including Great Britain, still persist in the subtropics of Asia and America. These forests disappeared when global climates cooled and dried down. The evolutionary lineage remains however, and despite the huge distance between these Asian and American forests, they seem to share a common history.

Conservation implications

Positioning protected areas to cover the evolutionary history of the forests will better protect global biodiversity. It also leads to an understanding of ecological resilience. The Indo-Pacific links of the eastern Africa forest tell us that they have been stable over vast periods of time, probably tens of millions of years. As they are adapted to stability, then they cannot cope with disturbance, providing guidance on how to best manage this unique area of species richness full of rare plants found nowhere else in the world.

Slik, J.W.F. et al. (2018). A phylogenetic classification of the world’s tropical forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Available online