21 August 2019

Minting a new Flora: How books help protect biodiversity

Compiling Floras is slow work but these books are vital tools in the conservation of plants.

Flora vs flora

If you’ve ever been curious to identify a plant, either in the UK or on your travels, you’ve most likely used a Flora to do so.

Whilst the ‘flora’ of an area is its plants and vegetation, a Flora is a publication that details the plant species of that area.

Floras are fundamental tools for scientists protecting global biodiversity in this age of habitat destruction and change. Until we understand which plants occur where, we cannot take action to protect them.

Often produced by an international community of taxonomists, they reflect the collaborative effort that scientists are making to understand biodiversity.

Having that information in a definitive reference work acts as a banner with which to engage key stakeholders such as governments, industry and the wider community.

What information is found within a Flora?

Published as physical volumes, or electronically, Floras provide:

- Information about the area of study

- Identification keys

- Plant descriptions and distribution data

- Notes on the plant habitat, or ecology

- Plant uses

- Notes on the taxonomic status of a species or tips for identifying

- Illustrations and photographs

A milestone for mint

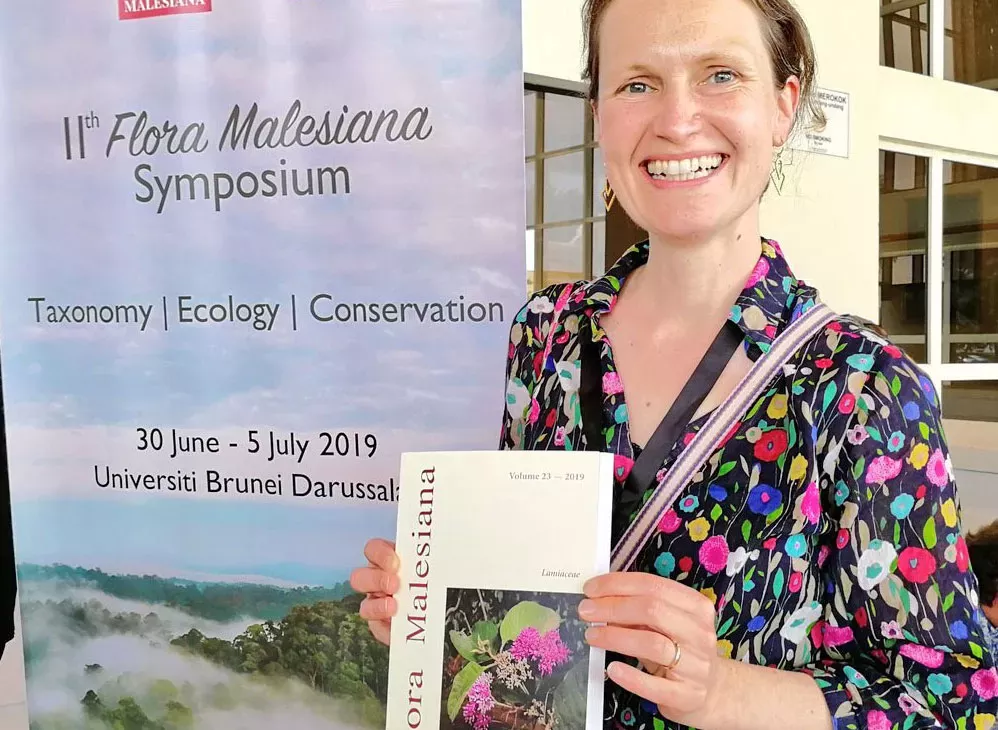

We have just added another important volume to this growing fountain of botanical knowledge with the recent publication of our Lamiaceae Flora Malesiana.

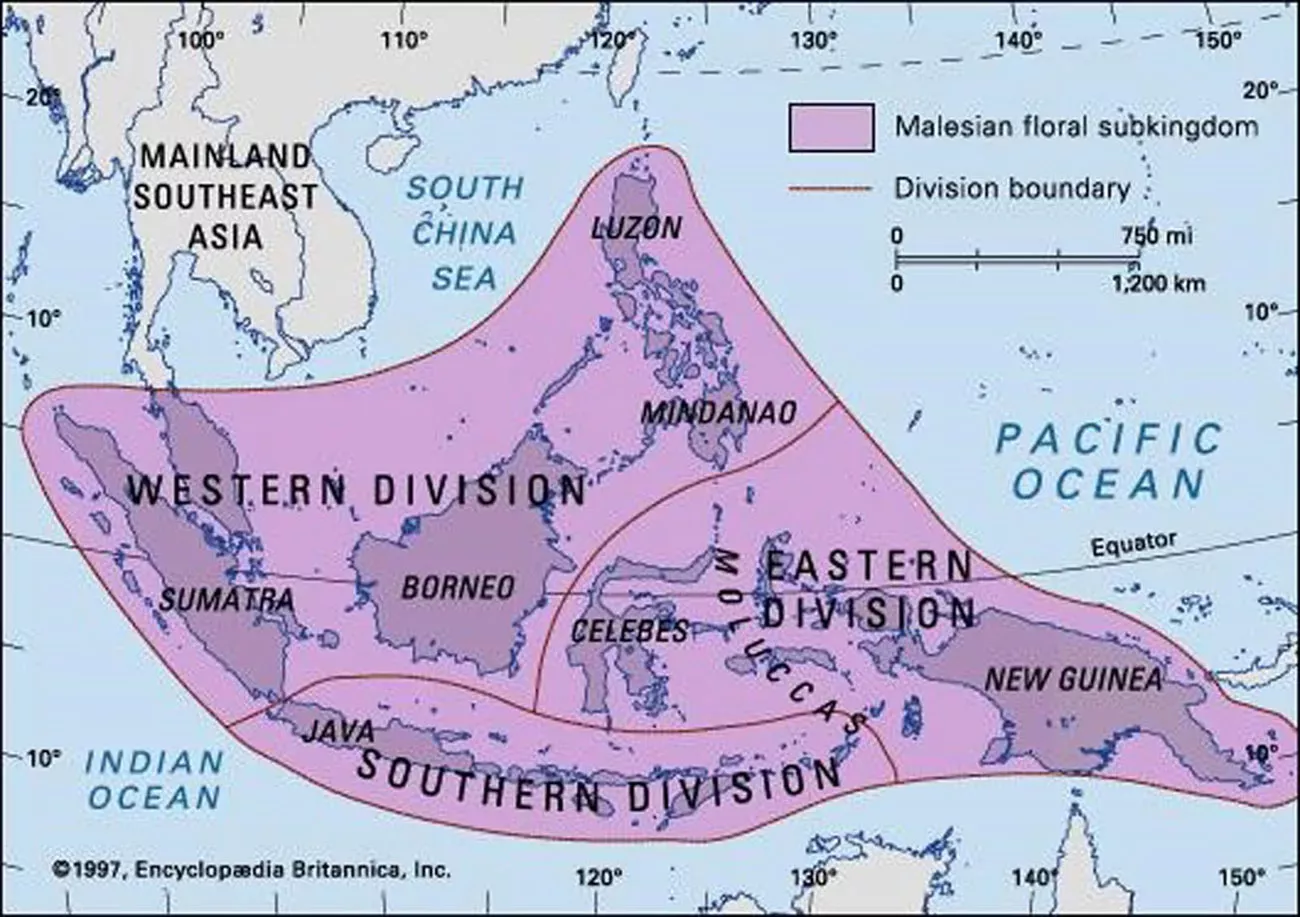

It describes the mint family in an area of Southeast Asia straddling the Equator between Sumatra and New Guinea; a region known to botanists as Malesia.

Recognising 50 genera and 304 species as native or naturalised in Malesia, 55 per cent of which are endemic to the region, it marks a significant step in our understanding of the Malesian flora.

The Lamiaceae (Mint family), the world’s sixth largest flowering plant family, is a focus of Kew’s taxonomic research. It's also an important component of the Malesian flora, with species varying from large timber trees such as teak (Tectona grandis) to culinary herbs such as Thai holy basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum), and ornamentals such as the brightly coloured Clerodendrum japonicum and the tropical vine Congea tomentosa.

A decade of knowledge building

An international team of taxonomists, coordinated by myself, have spent the last ten years compiling the required information.

We’ve travelled to Malesia on collecting trips with partner institutes and examined herbarium specimens found at Kew, as well as within the collections of many other herbaria around the world. During the process we’ve named and described 18 species new to science.

How exactly do you write a Flora?

The taxonomist’s primary data source is, of course, plant specimens, which makes fieldwork to find, collect and study living plants an important part of the process.

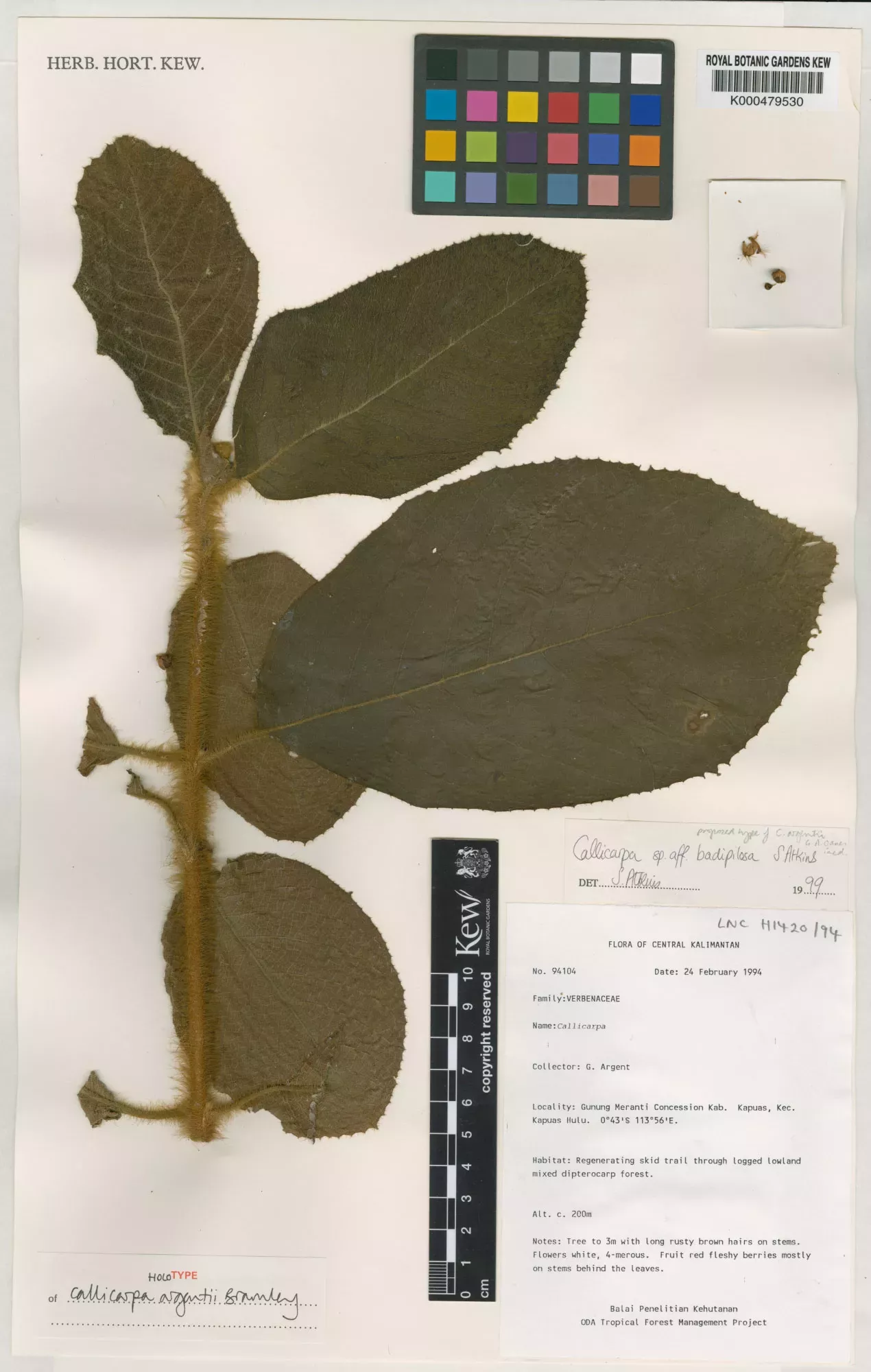

But the most vital element, to ensure that each species is fully understood, is access to herbarium collections, housed in approximately 2,800 herbaria around the world.

A herbarium specimen is a plant, or pieces of plant, that has been dried, pressed and mounted on to archival quality sheet, with a label detailing who collected it, from where and when, as well as any notes made at the time of collection.

The more specimens of a species a taxonomist studies, the more accurate their species description and understanding of where that species is distributed will be.

Kew is a great place to do this detailed work, since our Herbarium, founded in 1852, is one of the largest in the world, containing around seven million specimens. It is still being added to every year.

A lengthy process with a long lasting legacy

Depending on the number of plant species in the area in question, a Flora can be one volume covering all species, or multiple volumes.

When it comes to the Tropics, the most species rich areas of the world, this is a daunting task. Compiling the Flora of Tropical East Africa, for example, took 64 years and covered 12,000 species.

That’s nothing compared to Malesia, which is estimated to be home to 45,000 plant species. In fact, the Flora Malesiana project has been running since 1951 yet is only 30 per cent complete, with around just 30,000 species remaining to be written up.

Floras remain relevant for long periods after publication and the knowledge contained within them can be added to, or altered, as further discoveries of species are made.

The Flora of British India is still being reprinted more than 100 years after it was first published, since there is still no other completed Flora for India.

Looking to the future

Our team at Kew has committed to further work on the Flora Malesiana project, focussing on the taxonomy of species rich plant groups including the nettles (Urticaceae), buttercups (Ranunculaceae), ebonies (Ebenaceae), primroses (Primulaceae) and palms (Arecaceae).

It's a lengthy process but we will disseminate our knowledge as quickly as we can.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to: our numerous colleagues and partner institutes in Malesia, without whom this work would not be possible; to the Flora Malesiana Editor-in-Chief, Prof. Peter van Welzen; to the many herbaria that we have been granted permission to work in.

References

Van Steenis, C.G.G.J (1951) Flora Malesiana. Present and Prospects. Taxon, 1: 21-24.

Flora of West Tropical Africa (ebook)

Find out more about the Flora Malesia project.