15 September 2020

African cities under the threat of a new malaria vector

New research by Kew, in collaboration with the University of Oxford, reveals that an additional 126 million people in Africa could be exposed to malaria.

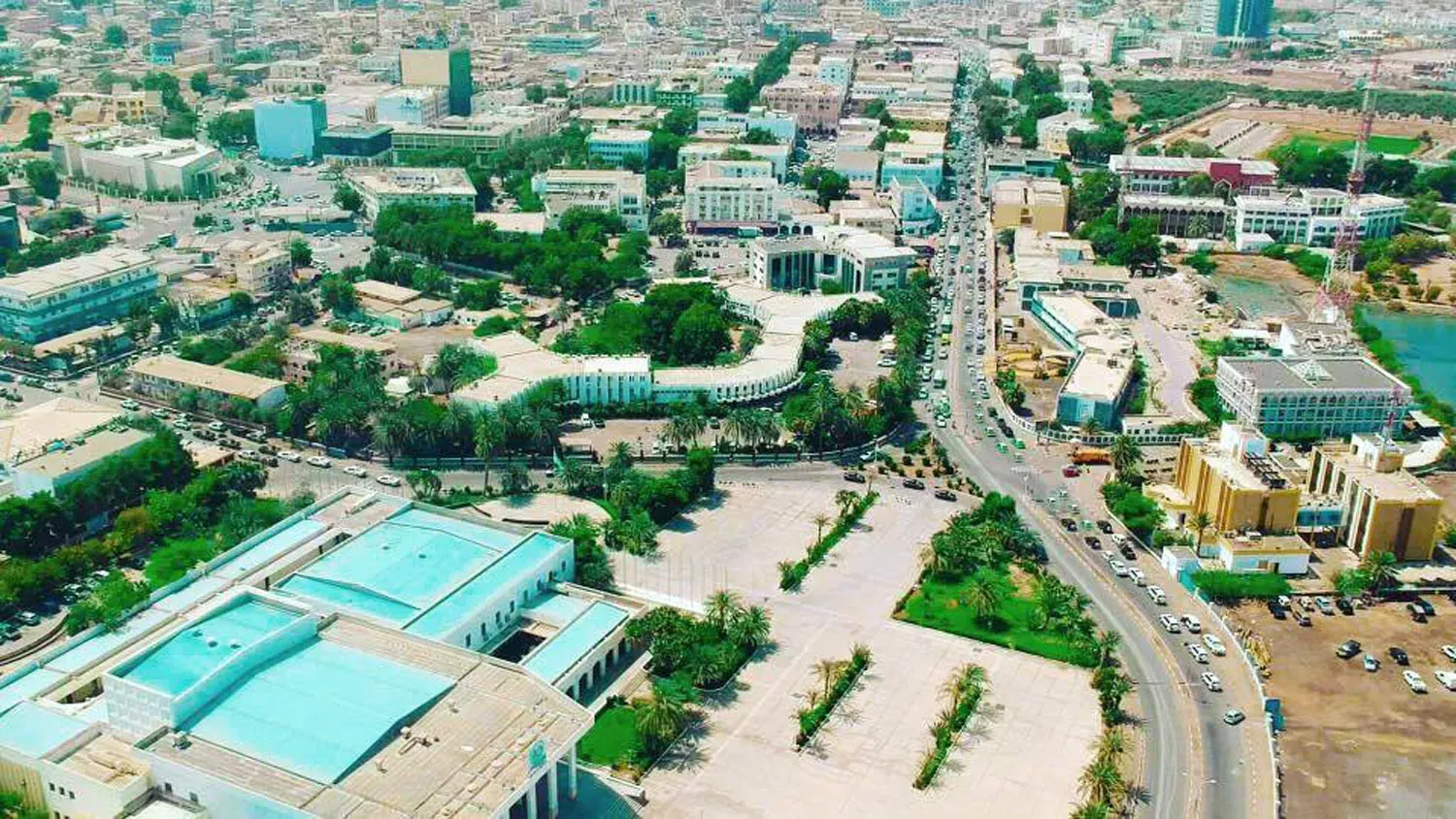

The Asian mosquito Anopheles stephensi, normally found in South Asia and across parts of the Middle East, is one of the few anopheline species that thrives in urban areas.

In 2012 an unusual outbreak of malaria occurred in Djibouti City in the Horn of Africa. Investigations discovered the arrival of An. stephensi.

Since its discovery, several increasingly severe outbreaks of malaria have occurred in Djibouti each year and the mosquito has now been detected in neighbouring countries, posing a worrying threat to Africa’s control and elimination of the deadly infectious disease.

Working with scientists at the University of Oxford, together we’ve been able to create maps that predict the suitable habitats available to this mosquito if it’s allowed to continue its menacing invasion across the African continent.

A taste for human blood

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites (Plasmodium sp.) that are transmitted to humans through the bite of a “vector” - Anopheles mosquitos.

Globally, there are around 228 million cases and 405,000 deaths per year, with over 90% of these cases and deaths occurring in Africa.

There are more than 140 anopheline species in Sub-Saharan Africa. Of these, only seven are considered dominant vectors of human malaria (including An. gambiae - "the most dangerous animal in the world", An. coluzzii, An. funestus and An. arabiensis).

These mosquitoes have evolved alongside humans, becoming increasingly specialised in seeking out blood.

Malaria control

Malaria transmission can be prevented by controlling the mosquito vector. The most effective methods use insecticide on treated bed nets or spraying it onto walls inside of homes.

Traditionally, the disease is more of a problem in rural Africa, partly due to the indigenous mosquitoes' preference for clean water to lay their eggs.

However, ongoing urbanisation has meant that many cities have developed areas for urban agriculture. This combined with poor water management, unplanned urban sprawl, and an emerging adaptation to dirtier water, means there are increasingly more environments for mosquitoes to breed.

This has led to a rise in malaria transmission within many African cities.

Mosquitoes in the city

But unlike the African species, the Asian vector An. stephensi is exceptionally well adapted to urban conditions and can seek out and utilise artificial water containers, such as household water storage tanks and garden reservoirs.

With over 40% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s population living in urban areas, the establishment of this urban mosquito in Africa, could affect millions.

The situation has even prompted the World Health Organisation (WHO) to issue a vector alert, meaning that countries in and around the Horn of Africa must take immediate action to monitor the presence of the mosquito and prevent it from breeding.

Mapping mosquito spread

A multi-year project initiated over a decade ago at the University of Oxford provided an extensive database of surveillance data, detailing the location of multiple mosquito vector species, including An. stephensi.

These data highlighted how far An. stephensi had spread over the last ten years.

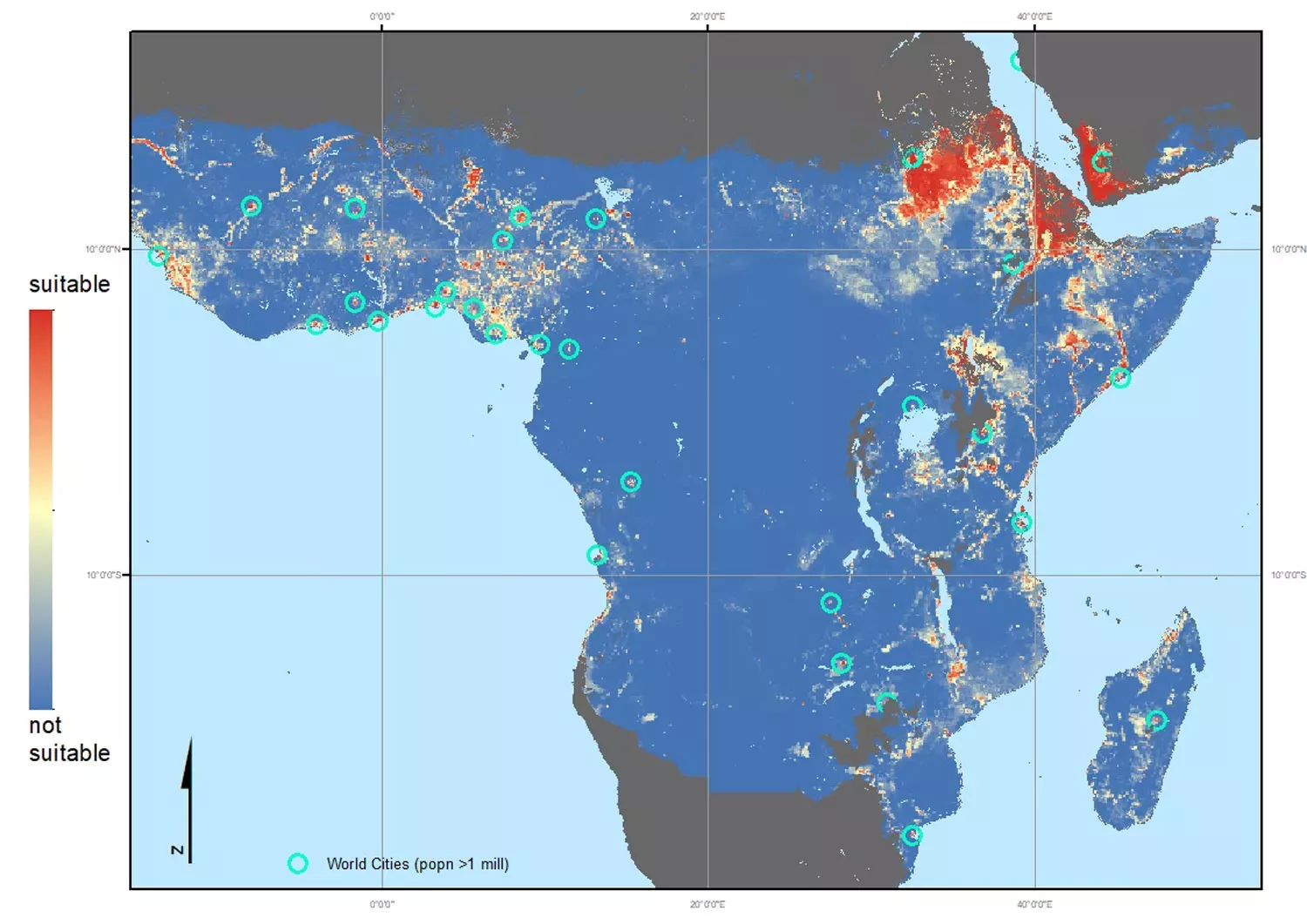

Using these data and spatial models that identify the environmental conditions that define the habitat of An. stephensi, we have predicted where in Africa the mosquito might establish if allowed to spread.

Examining these maps, in combination with data on the locations of many of the most densely populated cities across Africa, show that, were this mosquito to spread across the continent, an additional 126 million people could be exposed to malaria.

Clearly, this would be catastrophic.

Our work here shows that there is an urgent need for targeted vector control and prioritised surveillance to prevent this mosquito from causing a public health disaster.

Read the paper

Sinka, M. E., Pironon, S., Massey, N. C., Longbottom, J., Hemingway, J., Moyes, C. L. & Willis, K. J. (2020). A new malaria vector in Africa: Predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. PNAS