30 November 2018

Long live the weeds

Weeds: invasive aliens, useful plants, and everything inbetween. In this blog post, Library Graduate Trainee Will McGuire follows this tangled subject to some unexpected places.

A tangle of weeds

“From this position a shrubbery hid the greater portion of Putney, but we could see the river below, a bubbly mass of red weed, and the low parts of Lambeth flooded and red.”

News enough to make a London gardener’s skin prickle with fear… H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, with its vision of red Martian weed seeping through an undefended landscape, says a lot about the idea of weeds as malevolent, alien and invasive. Weeds can certainly be a scourge - but how else can we think about them, and what else are they?

Like weeds themselves, thinking about weeds can be a complicated and far-reaching tangle. They get everywhere! It is because of this that thinking about weeds also means popping up in unexpected places, often with fascinating results. From weaving, tea and soup (all from nettles) to Kew connections, imperialism and the pocked bombsites of post-Blitz London, we have a lot to learn from weeds.

“I have slept in nettle sheets…”

“I have slept in nettle sheets and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent pot-herb. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth…”

In her book, Weeds, Nina Edwards quotes the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell (1777-1844) extolling the virtues of nettles. So, how does a plant become a weed? The category is entirely subjective. When is the beloved ash tree a weed? It depends. Richard Mabey describes foresters calling ash ‘weed trees’ when they grow not in temperate woods but sprout unwanted among trees with more valuable timber. Most of all, it depends on human cultures, attitudes and histories, because ‘weed’ is not a scientific category, and there can be no thinking of weeds without thinking of the people who have burdened these diverse plants with their catch-all name.

Weedy language

The language we use to speak about weeds is telling. If a weed is a ‘plant out of place,’ as some definitions go, we might be taken aback by the violence with which the vague and subjective borders of this ‘place’ are policed; in English, weeds are ‘invasive,’ ‘alien’ ‘intruders’ to be ‘eradicated’ and ‘destroyed.’

There is historical precedence here. In Old English, Groundsel was called grundeswylige, which some (but not all) etymologists translate as ‘ground swallower’ - a poetic indication of the way in which hostile intentions are attributed to weeds. It is not only humans who are subjected to xenophobic language. This comparison does not wholly fit (some weeds really are able to cause immense damage to people and ecosystems), but, as Mabey says, “the shape of our cultural response to them is familiar” in an unsettling way that suggests deeply rooted hostilities.

Plants and empire

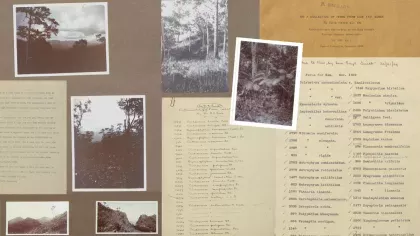

As well as signposting of this kind, weeds can also offer surprising perspectives on histories of injustice. Weeds thrive amid human activity, and imperialists have always been accompanied by weedy attendants, whether or not their presence was desired. Plants more generally have played an important role in the spread of empires; Kew’s imperial role was a vital one. To give but one example, until the 1940s, quinine was the only viable cure for malaria known to European science (see Kim Walker's blog post 'The fever tree: help us transcribe a bit of history' for more on this). Without quinine, provided by the cinchona tree, spread from its native South America in part by imperial plant hunters and botanical gardens, the British Empire would have had a harder time including in its swathes much of the lands where malaria is found. But it was not only celebrated medicinal plants like the cinchona tree that were used to grease the wheels of empire. Alfred Crosby’s book Ecological Imperialism shows us how weeds, too, had a part to play.

Weeds and empire

European weeds were vital for the spread worldwide of European livestock and those whose food depended upon it. Many weeds, like the grasses now on the South American pampas, were valuable food for grazing animals. Weeds and grazers had evolved together and, just as importantly, so had ‘Old World’ weeds and agriculture. These weeds could disguise themselves as crops, and they had adapted to the habits of livestock; not only were these plants capable of being trodden underfoot (or underhoof) and munched, of surviving in bare soil with no shade, but they were also readily spread by animals (including people), often advancing side by side, for example by the means of little hooks that snagged passing grazers. Moreover, as well as out-competing other plant species, weeds could be helpful to them, as Crosby points out: “The weeds, like skin transplants placed over broad areas of abraded and burned flesh, aided in healing the raw wounds that the invaders tore in the earth. The exotic plants saved newly bared topsoil from water and wind erosion and from baking in the sun.”

A green mantle

Weeds are some of the first plants to arrive on the scene after landscapes are burnt, disturbed or devastated. E. J. Salisbury (Director of Kew, 1943-1956) describes “the rapid clothing of the blackened scars of war by the green mantle of vegetation” in his 1943 pamphlet The Flora of Bombed Areas. Salisbury studied the bombed churchyard and nave of St. James’, Piccadilly (London): “Prior to bombing the churchyard flora consisted of its Catalpa trees and a few plants of Poa annua [annual meadow grass] between the pavement of tombstones. When… I examined the bombed nave last summer, there were over forty different species exclusive of fungi and mosses.” Most of these were, no doubt, weeds like buddleia, groundsel and Galinsoga parviflora (gallant-soldier), all of which are discussed in Salisbury’s Flora. (Coincidentally, gallant-soldier was also known as Kew weed, having escaped from the gardens after it was brought there from Peru in 1796).

Colour

For reasons like this, weeds are a recurrent theme in polemobotany, the study of plants affected by, or used, during military activity. At Kew, research and engagement in this field are led by James Wearn. In a previous blog post on plants and conflict landscapes (see below for a link), Wearn and Andrew Budden quote Arthur Hill (another former Director of Kew, 1922-1941) writing, in 1917, of “sheet of colour as far as the eye could see.” This was the Somme, Wearn and Budden explain: “Innumerable explosions had thoroughly mixed topsoil with the underlying chalk on the Somme. From the in situ seed bank, the soil’s back-up store house of plant propagules, germinated an array of ‘weeds’ which was striking to behold.”

Weeds: resistant, resilient, adaptable – and (if only sometimes) admirable?