24 December 2022

Three short tales of Kew Christmas Science

Ho ho ho, it’s Santa here, with some seasonal science for all to hear.

Plants and fungi are at the very heart of Christmas traditions dating back centuries. From the foods we love to eat, to the seasonal scents of December and the classic sights of Christmas day, it’s wildlife we rely on for them to exist at all.

Here at Kew there’s been much science to do, to understand the interesting lives, relationships and secrets of the species we hold most dear at this time of year.

Three short stories of Wintery Kew Science lie ahead… wrap up warm!

Tale No1 – The Christmas Chocolate Pollinators

There’s no doubt, Christmas is delicious. One of the many foods that gets extra love around this time of year is chocolate. It fills advent calendars, decorates Christmas trees, stocks supermarket shelves, and invariably causes some form of regret when consumed in great quantities.

But where does this Christmas treat come from?

Chocolate’s core ingredient is the cacao bean – the seed of the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao). This is a plant whose relationship with humans spans 5000 years, rooted in continental South Africa.

Today, a few variants are grown in plantations across the globe to satiate global demand. Both domestic and wild cacao plants require pollination. Without being fertilised, cacao plants do not produce beans and therefore the world’s chocolate supply would run dry. It is insects that cacao relies on for this task.

When thinking about insect pollinators, the famous bumblebee is what our brains tend to conjure up, but here, the hero of the story is the midge of the family Ceratopogonidae.

The humble midge tends to get a bad rap from humans – perhaps fairly – for the tendency of midge females to enjoy a snack on our blood to produce their young, but without them, we’d not have one of our sweetest delicacies.

Just why midges tend to frequent the flowers of cacao remains somewhat obscure, and with some cacao plantations struggling with pollination failures, Kew Scientist Phil C. Stevenson, alongside multiple key collaborators, sought to investigate if it was possible to optimise pollination and production.

The team carried out a full analysis of the cacao flower’s odour, a key component in encouraging pollinators to visit a plant. They found it was full of volatile compounds – chemicals that evaporate at low temperatures and produce the floral aroma.

Some of the compounds found resemble those normally associated with insect pheromones, or bacteria biofilms. Many midges feed on the haemolymph of insects instead of vertebrate blood, meanwhile it is biofilms that are a delicacy for midge larvae.

As some midge species’ whole life cycles are linked to the cacao tree, it’s possible that the plant’s floral odour has developed to resemble the things that its pollinator associates with survival, but we need to understand far more about both species to be sure, for now.

Importantly, the team’s success in understanding more about the midge-cacao relationship has huge potential impacts. Knowledge will be essential to improve the production success in cacao agriculture and in the conservation of wild cacao plants who form part of the broader ecosystems we inhabit.

For this Christmas treat, plenty of research lies ahead.

Sarah E. J. Arnold, Samantha J. Forbes, David R. Hall, Dudley I. Farman, Puran Bridgemohan, Gustavo R. Spinelli, Daniel P. Bray, Garvin B. Perry, Leroy Grey, Steven R. Belmain & Philip C. Stevenson (2019)

Floral Odors and the Interaction between Pollinating Ceratopogonid Midges and Cacao

Journal of Chemical Ecology 45, 869–878

Tale No2 – The DNA puzzles of Christmas Tree Fungi

The ultimate botanic Christmas symbol – the Christmas tree. We know the sight, we know the smell. Is it fathomable that such a beloved icon could ever disappear?

For one Christmas tree, this is the reality currently.

Most Christmas trees belong to one of three groups of conifer – spruce, pine and fir. This story’s tree belongs to the latter. It is Abies beshanzuensis, the rarest conifer tree in the world.

Just three wild trees of the species remain today, within a single site on Mt. Baishanzu, China. Unsurprisingly, the tree is considered Critically Endangered by the IUCN.

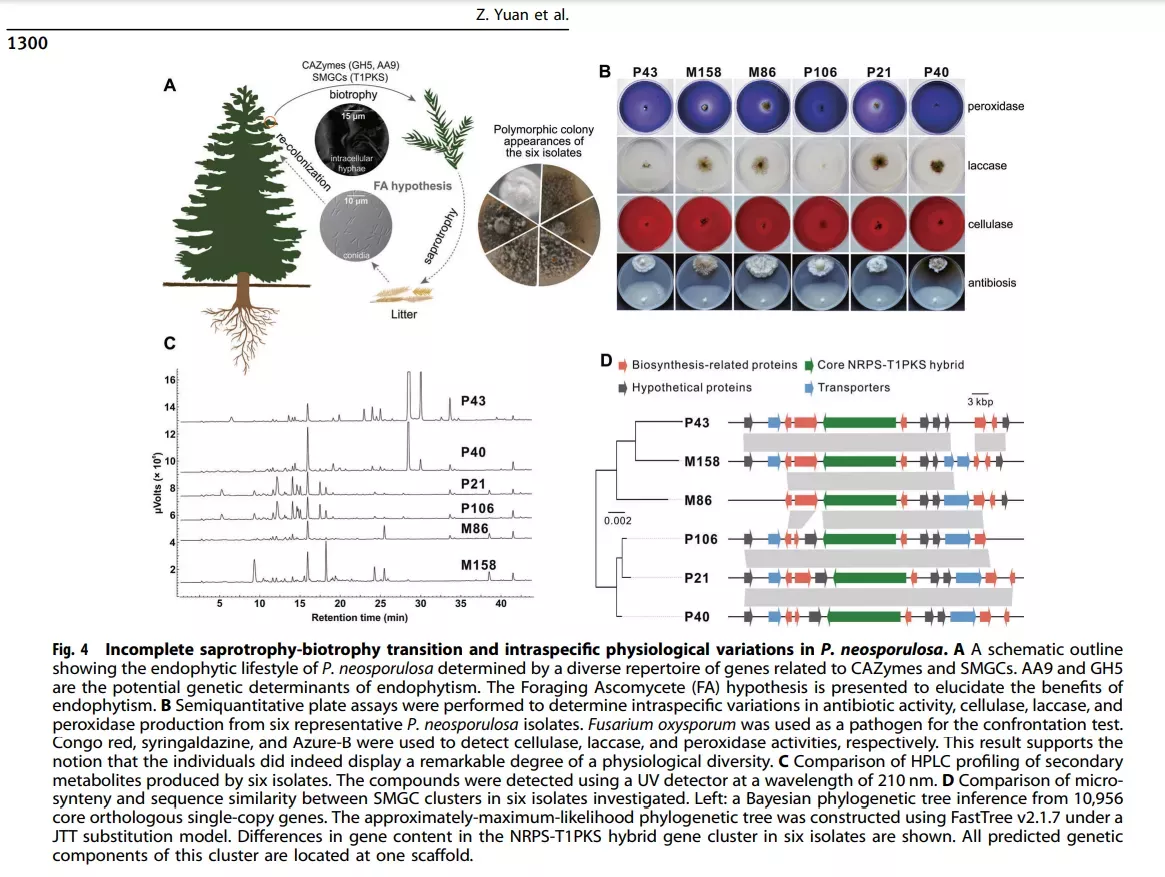

Here at Kew, researchers including Irina Druzhinina and colleagues have been studying a particular aspect of this relic fir – its fungi. Fungi are a universal presence in the world’s trees, referred to as ‘endophytes’ when living within the plants themselves. Scientists have for a long time pondered just how a fungus uses its genetic tools to take up such a lifestyle.

A.beshanzuensis firs host in their needles a recently discovered species of fungus Pezicula neosporulosa. Interestingly, the fungus has only been observed twice previously, in the Netherlands – very much the other side of the world. We likely don’t understand this rare species' full distribution just yet.

Within a population of just three host trees in China, the research team found extraordinary diversity in the fungus’ metabolic behaviours (how it produces energy), making it a perfect candidate to explore the big questions of evolutionary biology.

By comparing the genetics behind P.neosporulosa's metabolism with other fungus species known to enjoy a similar lifestyle, the team highlighted many similarities between them, hinting at some convergent evolution (unrelated species evolving the same traits). Moreover, P.neosporulosa's toolkit was found to be very broad, with the ability to exploit a number of opportunities for survival.

Studying the fine details of such relationships between plants and fungi contributes to a bigger picture of how whole ecosystems function and change, which will be critical if we’re going to keep these ecosystems around in the long run.

For this rare Christmas tree, and its complex fungi, hope lies with the young saplings currently growing here within the Kew Gardens nurseries, and in new areas in China, planted by our partners at the Chinese Academy of Forestry. Let’s hope for some Christmas success here!

Zhilin Yuan, Qi Wu, Liangxiong Xu, Irina S. Druzhinina, Eva H. Stukenbrock, Bart P. S. Nieuwenhuis, Zhenhui Zhong, Zhong-Jian Liu, Xinyu Wang, Feng Cai, Christian P. Kubicek, Xiaoliang Shan, Jieyu Wang, Guohui Shi, Long Peng & Francis M. Martin (2021)

The ISME Journal 16,1294–1305

Tale No3 – Christmas in the Tree of Life

We’re involved in the enormously collaborative ‘Darwin Tree of Life Project’, an ambition to create a biological roadmap navigating the evolution and properties of wildlife in Britain & Ireland. Here at Kew we aim to contribute towards the collecting of c. 2000 plant species and c. 17,000 fungal species that are native to our islands.

Brilliant. But what above the evolution and properties of all things festive?

That’s been a natural question for the project team. Quite a few of the species already mapped or destined for genetic study as part of this project are the species we consider most festive.

Take mistletoe (Viscum album), the plant with a romantic seasonal allure and a little-known parasitic lifestyle of sapping nutrients from the host tree on which it grows. It was collected by Kew in 2020, and in 2022, it became the largest genome (and 30 x the size of our own human genome!) of any species from Britain and Ireland sequenced in full, and will soon be added to the project’s public databases. This has taken enormous work from scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Edinburgh, who we’re proud to be partnered with.

Holly (Ilex aquifolium) is another to make the list so far. The prickly decorative plant seen adorning wreaths upon December doorways, was collected by Kew at the end of 2021 and awaits full sequencing. Ivy (Hedera helix) too joins it. Many have forgotten ivy’s role in Christmas folklore and the many mythic properties attributed to it over time, but still today it can be seen in Christmas cards and carols.

Ho ho ho - time for a 2023 Christmas update. A full holly genome is now available for all to download as part of the Darwin Tree of Life Project. Merry Christmas one and all!

Now, we look beyond Christmas to the future, and the thematic sequencing yet to be done!

On the list still to come is the sweet chestnut Castanea sativa – a staple of stuffings and a companion to the infamous brussels sprout (Brassica oleracea). Cherries (Prunus avium), plums and prunes (Prunus domestica), and redcurrants (Ribes rubrum) – all essential components of the traditional classics, Christmas pudding and plum pudding – also lie ahead for collection and sequencing.