31 August 2022

Kew’s vast and unique collections move online

A multimillion pound project to get eight million specimens online is well underway. But what lies ahead of unlocking one of the world's largest records of life?

Kew is embarking on one of the biggest projects in its history with the launch of a multimillion pound programme to digitise its entire collection of more than eight million plant and fungal specimens.

The four-year initiative, involving a third-party contractor (Max Communications Ltd) working alongside Kew staff and volunteers, will unlock a vast record of life on Earth, including rare historical specimens that are unavailable elsewhere.

Specimens in the virtual world

The mass digitisation drive, which started in August, is designed to make specimen records and images from this globally unique resource freely accessible to international scientists.

It will turbo-charge previous piecemeal efforts to move parts of the collection into cyberspace by ensuring that every plant and fungal specimen can be viewed from any computer or mobile phone anywhere in the world.

Kew’s dried specimens, which are stored in boxes in its Herbarium and Fungarium buildings, represent a treasure trove of information that can be used by scientists to build the tree of life. The granular detail about different species is also vital to help tackle critical global challenges, such as biodiversity loss and climate change.

Hidden stories

By trawling through this enormous library, dating back three centuries, researchers can drill down into the characteristics of individual plant and fungal species. The collection’s deep historical roots mean it can shed light on how the spread of species – from chestnut trees to cep mushrooms – has changed over the years.

Effectively, scientists can travel back in time to see how plants were distributed in the past, letting them reconstruct the extent of forests and other ecosystems that may have since been destroyed by human action or climate change.

The very oldest plant specimens at Kew were gathered in India in 1696 – even before the creation of the first botanic garden by the Thames in 1759 – and the Herbarium includes samples collected by 19th-century scientific pioneers and explorers such as Charles Darwin and David Livingstone.

It remains an active and expanding collection, with new accessions arriving at the rate of approximately 25,000 a year.

But while Kew today houses one of the largest and most diverse botanical and mycological collections, until now that hoard has been largely hidden from the world as most specimens are locked away in cupboards and only accessible if researchers are physically present at Kew.

The prize will be a world-leading digital repository of plant and fungal specimens, offering invaluable insights into some of the major challenges facing the planet, including mapping extinction risks for individual species and understanding the impact of climate change.

Significantly, even though only a fraction of specimens have so far been digitised, researchers are already using data from Kew and other major institutions in a wide variety of ways – from revealing that 60% of wild coffee species are threatened with extinction and mapping the status of endangered species of rosewood to understanding variations in myriad legumes used for food over the ages in different cultures.

Similarly, Kew’s historical collections are being leveraged to understand how wheat has evolved with changing environmental conditions and agricultural practices, in order to identify useful genetic diversity that may have been lost along the way.

The internet has the power to change all that by providing an online platform for high-quality images and information – including a unique barcode identifier for each specimen and crucial metadata that enables precise searches. However, to transform this promise into a viable research tool for a new generation of scientists, Kew has a huge amount to do.

Global demand for the information contained in Kew’s plant and fungal collection has never been greater. Yet only 16% of its collections have so far been digitised, placing Kew behind other botanical gardens in France, the Netherlands and the United States in taking data online.

Indeed, at the current run rate it would take another 175 years to digitise the Herbarium, where the backlog is greater than in the Fungarium.

Building a digital repository

To scale up the effort, digital archiving service Max Communications has now been contracted to fast-track the work, with the help of funding from the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

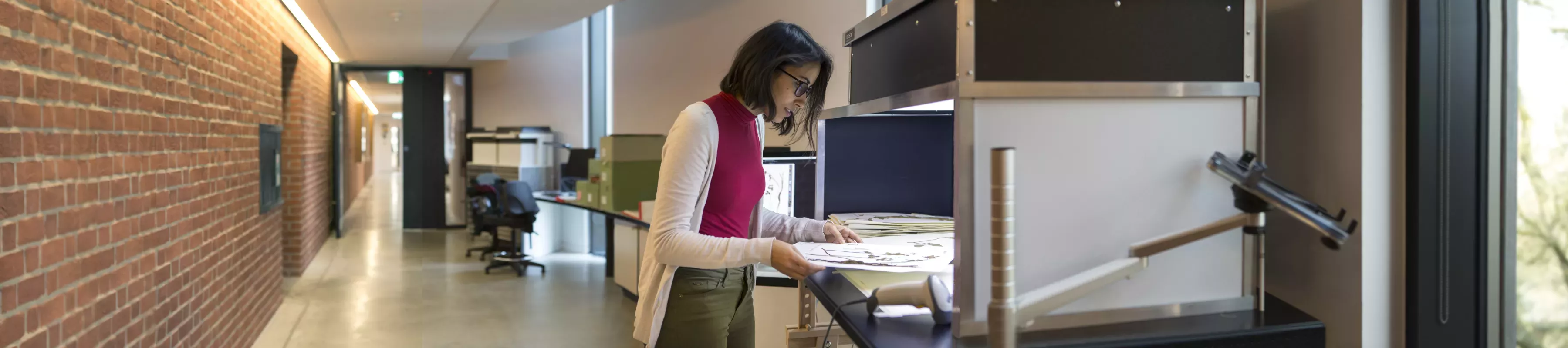

It will install 27 workstations through the Herbarium this year to image plant specimens and their labels, which will then be sent to India for transcribing. Data from the Fungarium will be sent to Max Communications starting in 2023.

At the same time, Kew is hiring additional staff and encouraging more volunteers to sign up to assist with the digitisation effort. This should help ensure speedy processing in the longer term, as new specimens are added in the years ahead, and it will also allow special care to be taken with certain groups of plants, such as orchids and palms, that are particularly complex or fragile.

An online backup

More soberingly, there is also another imperative for moving Kew’s collection online as quickly as possible: the risk of catastrophic damage from fire, flood or pests. This has been brought into sharp focus following recent devastating fires in Notre Dame, Paris and Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

There is particular concern about the risks faced by the two-thirds of plant specimens in the listed Victorian wings of Kew’s Herbarium, where fire protection is inadequate, pest control is limited and some areas lie below ground level within metres of the Thames.

So, digitising the collection will provide a crucial ‘back up’ copy of irreplaceable specimen data, helping to protect hundreds of years of public investment in the collection and study of plant diversity.