Imperial botany and the networks of science

The wealth of Britain’s empire was largely based on plants: from cotton and timber, spices, dyes and indigo, to gutta-percha.

Voyages like Hooker’s were partly concerned with mapping vital natural resources and discovering new ones. As a traveller, and later as Director of Kew, Hooker also relied on a wider network of plant collectors to provide him with more specimens from Britain's many colonies.

Australasia and the importance of plant distribution to science and empire

The geographical distribution of plants was a central concern for Hooker. He was puzzled, for example, by the species he had seen growing on widely-scattered islands. Like other naturalists he wondered how they had got there. One option was simply to assume that God had created them several times in their existing locations, but Hooker rejected this theory of multiple 'centres of creation' and sought a more law-like explanation. He assumed that each species had been created (by an unknown means) at a single time and place from where it had spread. However, this did not explain how species travelled over huge expanses of ocean.

Hooker’s solution drew on the work of his friend and colleague, Edward Forbes, Britain’s most vociferous proponent of single centres of creation. Forbes argued that the plants had migrated at a time when the isolated islands had been connected, but sea levels had since risen – as proposed by Lyell’s geological theories – leaving disconnected lands with common floras. Hooker explained the distributional puzzles of the southern ocean by hypothesising that a much larger Antarctic continent had once linked many of the now-isolated lands.

Darwin disagreed with Hooker and Forbes, baulking at the lack of evidence for the missing land, and proposed instead that anomalous distributions were better explained by seeds having migrated with the aid of bird and animals, or wind and ocean currents. He and Hooker argued over their competing theories for many years.

Studying plant distribution promised to shed light on the origins of species, but also had more practical implications. The wealth of Britain’s empire was largely based on plants: from cotton and timber, spices, dyes and indigo, to the gutta-percha (natural latex) so essential to Britain’s dominance of cable telegraphy.

Voyages like Hooker’s were partly concerned with mapping these vital natural resources and discovering new ones. But it was also hoped that such mapping would eventually reveal the laws that explained why particular plants grew where they did. Such laws would aid the search for new plants, and make transplanting crops between colonies much easier.

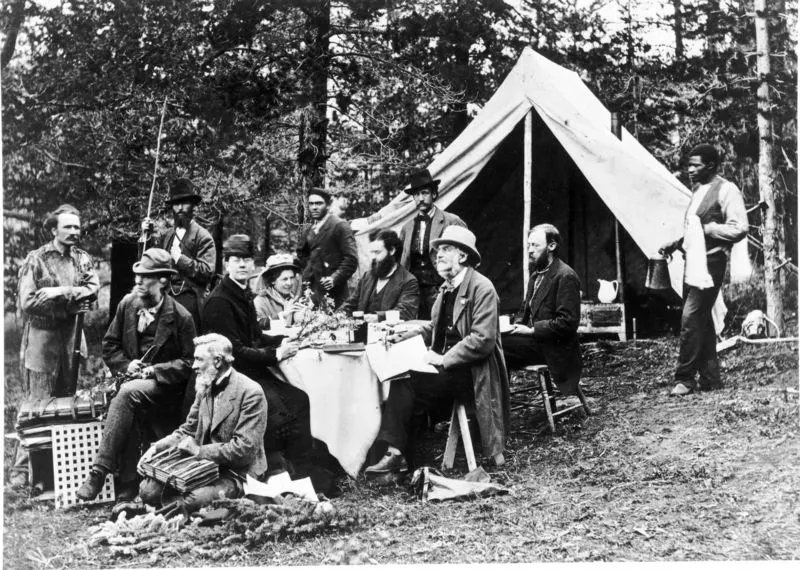

However, plant distribution studies required a global survey of vegetation and even after his voyage, Hooker needed many more specimens before he could write his floras. Unfortunately, the government’s funding of Kew during the middle decades of the century did not include provision for professional collectors, and neither William nor Joseph Hooker could afford to pay salaries out of their own pockets. Instead they had to rely on a diverse group of unpaid enthusiasts who eventually supplied the tens of thousands of specimens that allowed Joseph to complete his books while building his herbarium and reputation.

These colonial collectors, who were mostly men, included government officials, missionaries, gentlemen farmers, naval and army officers, private soldiers and shepherds. The collectors’ motivations were as diverse as their social backgrounds: some were trying to earn a living by selling specimens, but others saw themselves as men of science and aspired to join Britain’s scientific societies and publish in their journals. A few wanted to advance themselves socially by corresponding with other gentlemen about their common pursuits, and in many cases loneliness and isolation were powerful motivations for letter-writing. Additionally, an enthusiasm for the landscape and flora of their new countries occasionally inspired colonial botanists to tell the wider world about 'their' plants.

Relying on these largely unpaid correspondents to provide specimens forced Hooker to become an adept negotiator, whose botanical skills had to include discerning and satisfying the collectors’ diversity of expectations and desires. There were also conflicts with collectors when Hooker was unable or unwilling to give them what they wanted, as well as competition over collections with his rivals in other institutions and countries.

India and the Himalaya

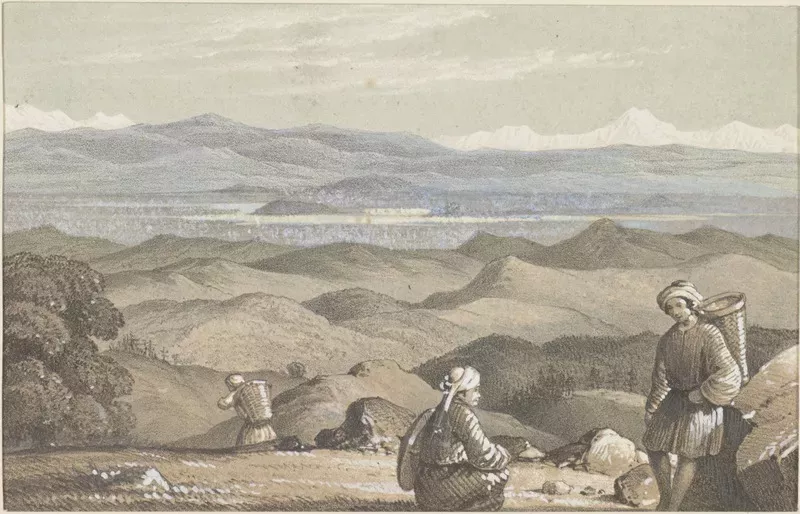

The imperial context and importance of Hooker’s work is also evident in his trip to the central and eastern Himalaya (1847 - 49). Hooker obtained a government grant for the trip and the Admiralty gave him free passage on the ships taking Lord Dalhousie, the newly-appointed Governor General, to India.

After visiting Calcutta, Hooker went to Darjeeling where he met Brian Houghton Hodgson, an expert on Nepalese culture, Buddhism and collector of Sanskrit manuscripts who was also a passionate naturalist. The two became close friends and Hodgson helped Hooker prepare for his trip into the Himalaya. However, by the time Hooker was ready to set off for Sikkim in 1848, Hodgson was too ill to accompany him and Dr. Archibald Campbell, the British government agent, went instead.

Sikkim - a small and impoverished state - was bordered by Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan, as well as British India. Its raja was understandably anxious not to annoy any of his powerful neighbours, so he and his chief minister, the diwan, were particularly suspicious of travellers like Hooker who surveyed and made maps during their travels. (Their suspicions proved well founded, as Hooker's maps later proved to have both economic and military importance to the British.)

When Hooker first sought permission to enter Sikkim the diwan made considerable efforts to prevent him, and even after pressure from the British administration forced the diwan to submit he obstructed their progress in various ways. He particularly urged them not to cross the northern border with Tibet during their explorations, but Hooker and Campbell knowingly ignored his order and the border violation was used by the diwan as a pretext to arrest and imprison them in November 1849. The British government secured their release within weeks by threatening to invade Sikkim. The elderly raja was punished with the annexation of some of his land and the withdrawal of his British pension, a response that even some of the British thought excessive.

... I doubt whether the world contains any scene with more sublime associations than this calm sheet of water 17,000 feet above the sea, with the shadow of mountains 22,000 to 24,000 feet high sleeping on its bosom.

Following his release, Hooker spent 1850 travelling with Thomas Thomson in Eastern Bengal and the two returned to England in 1851. Together they wrote the first volume of a projected Flora Indica (1855), which was never completed because of a lack of support from the East India Company (although Hooker eventually produced the Flora of British India, 1872 - 1897). However, the introductory essay on the geographical relations of India’s flora was to be one of Hooker’s most important statements on biogeographical issues.

Altogether Hooker collected about 7,000 species in India and Nepal and, on his return to England, managed to secure another government grant while he classified and named them. The first publication was the Rhododendrons of the Sikkim-Himalaya (1849 - 51), edited by his father and illustrated by Walter Hood Fitch, whose fine drawings enriched many of both Hookers’ publications.

Hooker and Campbell’s travels added 25 new rhododendron species to the 50 already known, and the spectacular new species they introduced into Britain helped create a rhododendron craze among British gardeners. Hooker’s journey also produced his Himalayan Journals (1854), which were dedicated to Darwin.

Text by Dr Jim Endersby. Reproduced with the permission of the author and Oxford University Press. Full biography also available free online on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website.

Joseph Hooker and the networks of nineteenth century science

One of the most notable features of Joseph Hookers archive is the variety of correspondents that Hooker was in contact with during his life time.

Perhaps most famously, Hooker was lifelong friends with Charles Darwin and their scientific discourse helped shape Darwin's theory of the evolution of species.

Shortly after his return from the Antarctic, Hooker received a letter from Darwin congratulating him on his achievements, offering specimens from Tierra del Fuego, and asking whether Hooker would be interested in classifying the plants Darwin had gathered in the Galapagos. At this time, the two men hardly knew each other, having met only once, shortly before Hooker set sail. Nevertheless, Hooker was flattered by his scientific hero’s attention and began the Galapagos work.

These first letters marked the beginning of a lifelong correspondence, through which the two became friends and collaborators, and debated their many scientific interests – notably over questions of plant distribution. The rapid deepening of Hooker and Darwin’s friendship is evident from a letter Darwin wrote on 14 January 1844: ‘I am almost convinced,’ he told his new acquaintance, ‘(quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable,’ adding that ‘I think I have found out (here’s presumption!) the simple way by which species become exquisitely adapted to various ends’ (Burkhardt and Smith 1987: 2). The ‘simple way’ was, of course, natural selection, and Hooker was the first in the world to hear of Darwin’s secret.

Hooker also correspondent with members of Darwins family, including his sons William Darwin and Francis Darwin and attended numerous family events.

Hooker was also a close correspondent and friend of other noted scientists during the nineteenth century. He wrote numerous letters to the American botanist Asa Gray and even travelled to America to visit Gray in 1877. Gray first met Joseph Hooker in 1838, during a trip to Europe to reconnoitre botanical libraries and herbaria in Europe.