Hooker's career and legacy

Hooker began his career as a surgeon in the navy.

Unable to travel as a gentleman naturalist of independent means Hooker used his medical qualification obtained at the University of Glasgow to secure an appointment as Assistant Surgeon on HMS Erebus for the Ross expeditions to the Antarctic (1839-1843). He used this opportunity to do much botanising in the Southern Ocean nations, especially New Zealand.

Upon his return, Hooker undertook to find employment. In 1845, he was a candidate for the chair of botany at the University of Edinburgh. After failing to win the professorship, his father’s contacts helped him secure work at the Geological Survey of Great Britain from 1847–48, but he still had no permanent position.

In 1847 Hooker gained a government grant to travel in India and the Himalayas, setting sail in November of that year and remaining in India until 1851. He was the first westerner to set foot in the more remote northern areas of the Himalaya, once roaming so far that he got himself imprisoned by the Rajah of Sikkim for exploring where he should not have. In India he collected around 7,000 plant species including 25 new species of Rhododendron that helped create a craze among British gardeners.

Hooker was more than just a plant collector, he was an interrogator of the natural world, keenly observing the lands in which he travelled so that he could describe, classify and understand what was all around him. This combination, of plant collecting and interpreting the data he collected, earned Hooker a global reputation as an expert in plant distribution. For example, in India he sought evidence in the botany and geology of the highest mountains in the world that would support Darwin's theory On the Origin of Species, to be published famously in 1859.

The 1850s also saw the appearance of several of Hooker’s most important publications: accounts of the botany in the countries he explored including the beautifully illustrated Rhododendrons of Sikkim Himalaya and Colonial floras of New Zealand. He would also use his collections and those of others to compile a world flora in the following decades. The Genera Plantarum, prepared with co-author George Bentham over more than 25 years, was finally published in 1883 and has been called the most outstanding botanical work of the century. It describes over 7,500 genera and nearly 100,000 species and established the Bentham-Hooker model for plant classification.

In the same period Kew that had grown substantially since William Hooker had been put in charge. The Gardens had been increased from eleven acres to over 300 acres, containing more than 20 glasshouses and over 4,500 living herbaceous plants. Faced with this enormous expansion, the government finally agreed that the director could not cope alone and their decision brought a conclusion to Joseph’s long search for secure, paid employment; he was appointed Assistant Director on 5 June 1855.

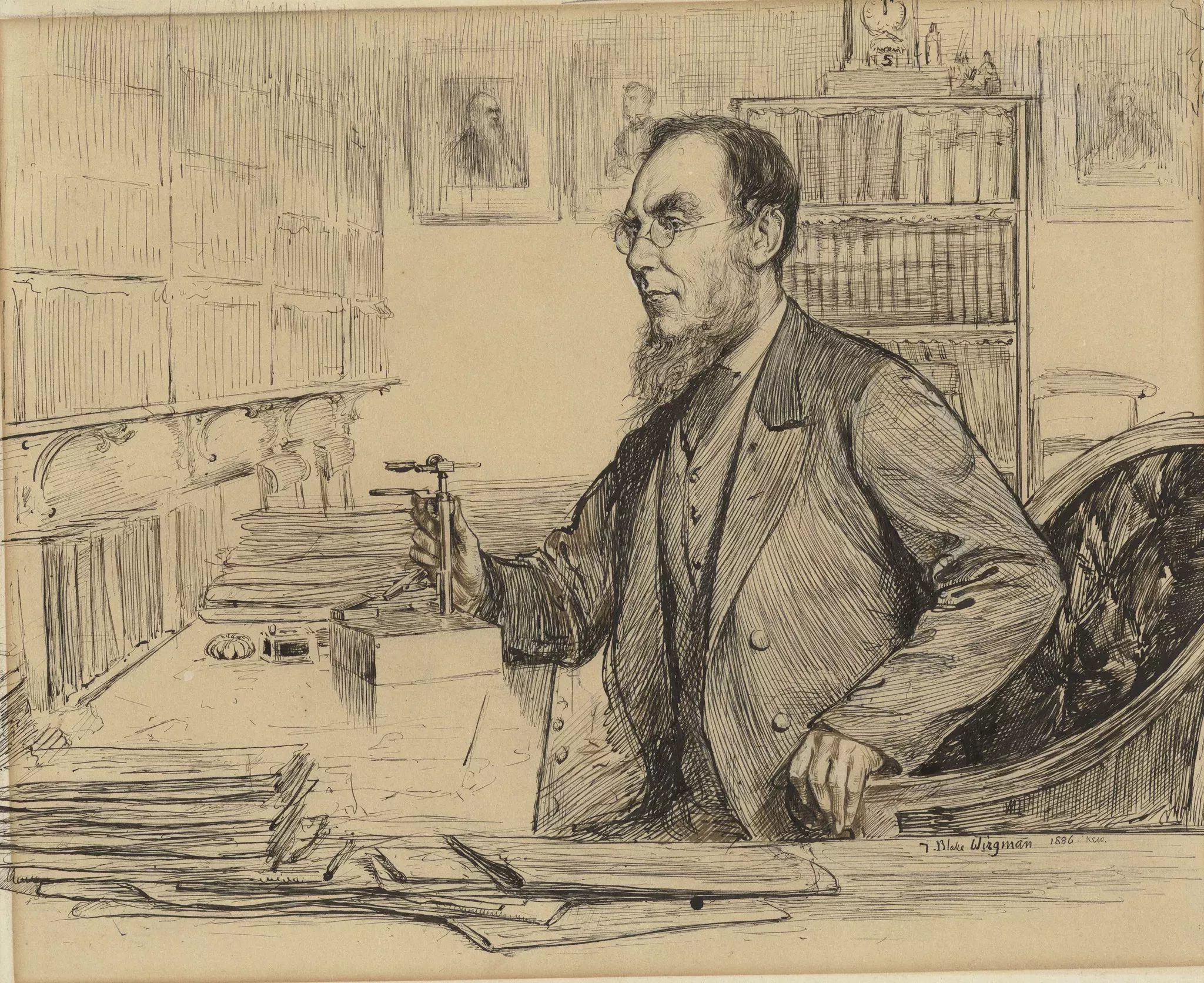

Kew under Hooker

In 1865 Hooker’s father died and Joseph succeeded him as director of Kew. Hooker was by this time a highly-regarded botanist with a worldwide reputation, nevertheless he might not have secured the position without his father’s constant assistance. William Hooker had even offered to leave his vast private herbarium to the nation as long as Joseph were appointed to succeed him.

Hooker remained Director of Kew until his retirement in 1885. These twenty years were marked by the continuation and expansion of Kew’s imperial role. In 1859–60, William Hooker and Kew had provided essential assistance in the ‘transfer’ of Cinchona (the tree from whose bark quinine was made) from South America to India. This enabled this crucial crop to be grown in a British colony with plentiful supplies of cheap labour, resulting in cheaper, more reliable supplies of the drug that was essential to combating the malaria endemic to many tropical colonies. The success of the Cinchona transplantation was emulated under Joseph Hooker’s direction in the 1870s when rubber seeds (Hevea brasilensis) were removed to be grown in British colonies, especially in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore and Malaya.

As well as expanding the imperial role of Kew by transplanting commercial plants throughout the British Empire, Hooker also grew the Gardens' assets on the home soil of Kew. During his travels Hooker had contributed to the improvement of Kew through the donation of plants to the collections: his dried plant specimens helped swell the herbarium collection and the many new species of Rhododendron Joseph sent back to his father from the Himalayas were added to what had previously been the 'Hollow Walk', transforming it into the Rhododendron Dell.

As Director, Hooker continued to grow the dried and living plant collections at Kew through his network of collectors. So much so that it became clear additional space was required to house the herbarium collection, and in 1871 Hooker's request for a purpose-built extension was granted. Under his aegis the Garden and Arboretum was laid out according to the Bentham-Hooker classification, which he had developed in collaboration with George Bentham. Other notable built additions included the first Jodrell Laboratory and the Marianne North Gallery, donated by the Victorian artist and traveller, to house 800 of her botanical paintings.

The public function of Kew

The public function of Kew became a source of controversy in various ways during Hooker’s tenure as Director. He asserted that the Gardens' ‘primary objects are scientific and utilitarian, not recreational’ and complained about the need to create elaborate floral displays for those he regarded as ‘mere pleasure or recreation seekers … whose motives are rude romping and games’ (Desmond 1995: 230, 234). Given these views, it is hardly surprising that he continued the tradition of allowing only serious botanical students and artists to enter the Gardens during the morning, and resisted all attempts to extend the Gardens' opening hours for the general public.

Behind this opposition to admitting the public and providing better facilities for them lay an anxiety about the scientific standing of Kew and of botany more generally. Botany continued to enjoy enormous popularity with non-professionals and was associated in the public mind with respectable middle-class activities, such as gardening and flower-painting. It was also particularly popular with women – at a time when the world of Victorian science was almost entirely dominated by men.

In the 1870s, anxieties over the status of Kew – and over his personal standing in the scientific world – drew Hooker into conflict with Acton Smee Ayrton, the first commissioner of the Office of Works (which had taken over control of Kew from Woods and Forests in 1850). Hooker’s notorious irritability – even Darwin described him as ‘impulsive and somewhat peppery in temper’ (Barlow 1958: 105) – probably contributed to the conflict, but the immediate focus of what became known as the 'Ayrton controversy' was Richard Owen’s Natural History Museum at South Kensington.

By 1872, Ayrton had already made several attempts to cut public spending on scientific institutions and had clashed with Hooker several times as he tried to assert his authority over Kew. He now privately consulted Owen as to the future of the rival herbaria and Owen, not surprisingly, proposed that Kew’s collections be transferred to the Natural History Museum – a proposal that would have reduced Kew to a mere public park. Hooker resisted this strongly, calling in every prominent British man of science he knew, including Darwin and Lyell, to protest publicly against the proposed change. After debates in both houses of parliament, Hooker and the Darwinians succeeded in getting Ayrton transferred to the office of Judge Advocate General. Both Kew and the Natural History Museum retained their respective collections and at the general election of 1874, Ayrton lost his seat.

Hooker's public dissemination of science

Yet despite Hooker’s autocratic opposition to anything he regarded as diluting Kew’s scientific role, he was not opposed to widening public participation in science.

In 1866, he addressed the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), whose meetings the general public were encouraged to attend, and delivered a lecture on ‘Insular Floras’ in which he finally gave up what he now called ‘sinking imaginary continents’ and instead adopted Darwin’s theory of plant distribution by migration. Hooker’s involvement with the BAAS also included presiding over the department of zoology and botany in 1874 and over the geographical section in 1881.

In 1873, Hooker was elected president of the Royal Society where he instituted various reforms designed to broaden public participation in the society, including the ladies soirées. When he retired from the presidency in 1878, Hooker was particularly proud of the £10,000 he had helped raise which allowed the restrictively-high membership dues to be reduced.

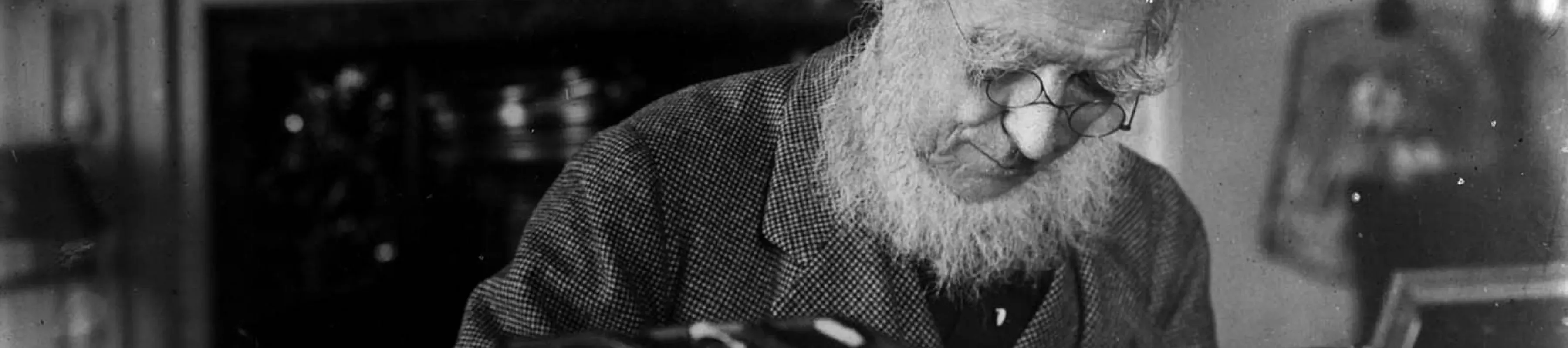

Hooker, along with Thomas Henry Huxley, was among the founders of the X Club, a private dining society that supported Darwinism and opposed those they saw as obstructing scientific progress, especially traditional churchmen. In letters to Huxley, Hooker was forthright about his dislike of theological dogmatism, sacerdotalism and ceremony, but nevertheless remained a church-going Anglican and agreed to act as godfather for Huxley’s son.Hooker retired from his post at Kew in 1885 but continued to work on botany until his death in 1911, aged 94.

Hooker's place in history

Hooker was highly-regarded in his lifetime and received numerous honorary degrees including ones from Oxford and Cambridge. He was created C.B. in 1869; K.C.S.I. in 1877; G.C.S.I. in 1897; and received the Order of Merit in 1907. The Royal Society gave him their royal medal in 1854, the Copley in 1887, and the Darwin in 1892. He received numerous prizes and awards from both British and foreign scientific societies; the full list of his honours runs to ten pages (Huxley 1918: 507–517).

Although botanists have long-recognised Hooker’s taxonomic skills and his pioneering work on distribution, his wider reputation has been somewhat obscured by his close relationship with Darwin. When Hooker appears in histories of 19th century science, it is almost invariably as a minor character in Darwin’s story and his own work, attitudes and opinions have been neglected as a result.

However, recent scholarship has begun to recognise that Hooker’s preoccupations – especially taxonomy, botanical distribution and the disciplinary status of botany – are central to understanding the material practices of 19th century natural history, particularly in its imperial context.

Hooker’s correspondence with his colonial collectors illustrates how the practices of 19th century natural history need to be seen as a complex series of negotiations, rather than in terms of straightforward metropolitan dominance; much existing historiography has assumed that those in the colonies were passive servants of imperial science, and as a result their interests and careers have been neglected.

Hooker’s career also casts doubt over standard accounts of the professionalisation of British science, particularly the assumption that he and the other young professionalisers (especially those in the X Club), were determined to replace institutions based on patronage with those based on merit: Hooker inherited Kew from his father and bequeathed it to his son-in-law – and the role of patronage in these transitions is unmistakable.

Likewise, Hooker’s equivocation over Darwinism undermines the assumption that it functioned as a unifying ideology for the professionalisers. While he welcomed and embraced natural selection as allowing naturalists to form ‘more philosophical conceptions’, he also stressed that both Darwinists and non-Darwinians, ‘must employ the same methods of investigation and follow the same principles’ (Hooker 1859: iv). This apparent ambivalence probably resulted from his need to maintain good relations with his diverse collecting networks, whose members were often deeply divided over the species question. As is illustrated by the Ayrton controversy, conflicts over Darwinism were potentially dangerous to a man in Hooker’s position.

Hooker died in his sleep at midnight at home on 10 December 1911 after a short and apparently minor illness. He was buried, as he wished to be, alongside his father in the churchyard of St Anne’s on Kew Green. His widow, Hyacinth, was offered the option of burying him alongside Darwin in Westminster Abbey, but perhaps she understood that – despite the importance of his relationship with Darwin – it was botany, Kew Gardens and his father who should determine his final resting place.

Text by Dr Jim Endersby. Reproduced with the permission of the author and Oxford University Press. Full biography also available free online on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website.