18 March 2016

Food of the gods: a brief history of chocolate

As Easter approaches we look at the history of chocolate and the role Kew has played in the spread of the cocoa bean.

The origins of chocolate

Chocolate is now a ubiquitous foodstuff, so it’s easy to forget that the cocoa bean was unknown in Europe until the 16th century.

The word ‘chocolate’ is of uncertain origin, but the most common theory is that it comes from the Nahuatl word ‘xocolatl’, which is a compound of ‘xococ’ (bitter) and ‘atl’ (drink). The cocoa bean originated in South and Central America, and has a long history there.

The Olmecs of Mexico are known to have cultivated cocoa beans as long ago as 400 BCE. In Northern Belize, carbonised cocoa beans have been found that date back to circa 100 CE, as have fragments of cocoa-rind that could come from as early as 1100 BCE.

Xocolatl and cocoa as currency

Unlike modern chocolate, xocolatl was consumed in liquid form. It was mixed with spices including chilli and vanilla. Cocoa beans were valuable, being used as a form of currency by both the Aztecs and the Mayans, and an exchange rate existed between cocoa beans and the Spanish real. Cocoa beans being ‘forged’ by empty shells being filled with earth.

Consumption of xocolatl seems to have been limited to the upper classes – among the Aztecs, a lower class person caught consuming cocoa beans could be condemned to death. The Aztec emperor Montezuma was noted for his consumption of large amounts of xocolatl, and his fondness of the beverage is described in W. H. Prescott’s Conquest of Mexico:

"The emperor took no other beverage than the chocolatl, a potion flavoured with vanilla and other spices, and so prepared as to be reduced to a froth of the consistency of honey, which gradually dissolved in the mouth.

This beverage, if so it could be called, was served in golden goblets, with spoons of the same metal or of tortoise –shell finely wrought. The emperor was exceedingly fond of it, to judge from the quantity, - no less than fifty jars or pitchers being prepared for his own daily consumption. Two thousand more were allowed for that of his household."

It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that Linnaeus gave it the name Theobroma cacao when he included it in his 1753 work Species Plantarum.

Chocolate arrives in Europe

The cocoa bean was initially brought to Europe by missionaries returning from the new world.

Xocolatl, being a bitter and spicy drink, did not initially sit well with the European palate. Chocolate became popular with the European nobility after being introduced to the Spanish court by Kekchi Mayan nobles who had been brought over by Franciscan monks. Europeans sweetened the bitter drink with spices, including cinnamon and vanilla, rather than taking it with chilli and pepper.

Chocolate rapidly came to be viewed by the European nobility as an aphrodisiac and a kind of panacea. Chocolate was initially very expensive, as the process of importing it was long and difficult, and cocoa beans were often spoilt in transit.

Therefore as in Mesoamerica, chocolate was in Europe initially only a foodstuff for the nobility. Just like coffee was popular among male members of the nobility during this period, chocolate became the drink of choice for aristocratic women.

Chocolate for all

Chocolate began to lose its upper class associations in the latter half of the 18th century. It wasn’t until 1828 that chocolate became a substance that could be sold to a mass market.

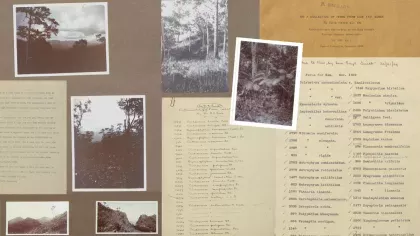

This happened after Conrad van Houten invented a press that made the production of solid chocolate a possibility. The above letter sent by G.H.K. Thwaites to Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (the second official director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew) was accompanied by some Sri Lankan cocoa beans. Thwaites wanted Hooker to send these to Messers Fry and Sons of Bristol (chocolate manufacturers still well-known today) for an opinion on the beans’ quality.

We also see evidence of Kew’s involvement in the chocolate trade in the following statement from the minute William Thistleton-Dyer, Kew’s third director, sent to the Secretary of the Board of Agriculture upon his retirement: ‘[the export value] of cocoa was £4 in in 1892, rising in 1904 to over £200,000.

This has been accomplished under Kew guidance by an officer trained at Kew.’ We can see that Kew’s connection with the chocolate industry started a long time ago – and is still strong to this day. The 19th century shift in cocoa plantations from the Americas to Asia and Africa has led to Africa, in particular Ghana, now being the world’s largest producer and exporter of cocoa beans.

- Francesca Railton -

Library Graduate Trainee

Further reading

Davies, N. (1980). The Aztecs. University of Oklahoma Press.

Hammond, N. (2004). The Maya. Folio Society; 5th Printing edition.

King, M. (2015). Tea, Coffee & Chocolate: how we fell in love with caffeine. Oxford.

Prescott, W. H. (1843). The Conquest of Mexico.