26 May 2017

Conserving Chinese pith paintings

Collections conservator Eleanor Hasler on the challenges of and techniques used in conserving a collection of beautiful but fragile Chinese pith paintings.

Pith paintings

While travelling in China during the first half of the 19th century it became common for Europeans to collect small, attractive watercolour paintings by local artists. These ‘export paintings’ usually depicted scenes of everyday life in China as well as decorative images of birds, insects and flowers. They were often treated as souvenirs, bound in albums and taken back to Europe. The paintings are very striking in their vibrant colours and translucency, which is due to the support on which they are painted. Instead of being made from plant fibres matted together, as with traditional paper, the soft white support is a thin slice of the stem of the Tetrapanax papyrifer plant. The velvet-like texture of the pith ‘paper’ lends itself well to the application of watercolours, and its ability to absorb water to alter the surface characteristics means the paint layer is raised, creating an attractive embossed surface.

Pith paper at Kew

William Jackson Hooker, while Director of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, was very interested by the source plant of pith paper and asked for samples and plants to be sent from China back to Kew so that he could identify it.

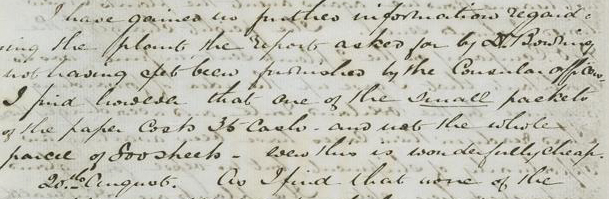

Letters such as this one from Sir John Bowring, Consul at Canton 1848–1853 (taken from the Director’s Correspondence collection), describe the pith items being sent back from China for Hooker to study and the efforts made to obtain live plants. After a number of plants died onboard ships, a section of stem and some leaves of the pith plant managed to survive the journey back to England and with the help of a drawing of the plant Hooker was able to describe the plant as Aralia papyrifera in 1852, now Tetrapanax papyrifer (Hook.) K. Koch. The Economic Botany Collection at Kew has a fascinating collection of pith paintings, pith flowers and implements used for pith production in its collection due to William Hooker’s fascination with the plant and his interest in its economic value.

Ward album of pith paintings

As pith paper ages it becomes very brittle, which is why a collection of pith paintings came to the conservation studio in need of repair and rehousing. The paintings were presented in an album, a traditional way of housing the paintings, with the original mounting method in place of silk ribbons adhered at the edges of each painting.

The album had been presented to Kew in 1964 and had belonged to Dr Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, the inventor of the Wardian case – an airtight, portable greenhouse used to protect live plant material during transportation. Coincidently, it is likely that the Tetrapanax papyrifer plants that finally survived the journey to Kew would have been stored in Wardian cases during the voyage.

Condition of the paintings

The paintings in the album were so fragile that the pages of the album could not be turned without causing further damage. In all there were 12 paintings of flowers and insects, all with spits and some with large losses. Although the album showed the traditional way of displaying and housing paintings such as these, a decision was made to remove the paintings from the album and mount each one separately, which meant that not only were they on a more stable backing but each one could also be displayed without any further handling. The empty album would be stored alongside the paintings so that they are kept with their original housing method.

Treating the paintings

Pith paper is a unique support and behaves very differently to rag or woodpulp paper. It is very hygroscopic – water swells the support, distorting it, and if used excessively it can make the plant cell walls collapse so that the paper looses its velvet-like quality. This meant that I had to carefully control the amount of moisture I used when applying adhesive and repair tissue to the backs when mending the tears. As there was often watercolour applied to the back of the paintings, a common technique in Chinese watercolour paintings used to increase opacity, I was unable to line the paintings, so I used thin strips of very thin Japanese tissue with a weak methyl cellulose adhesive to mend the tears. By working on the light box I was able to see how the tear aligned as the paper is so translucent. However, away from the light source the repairs were invisible from the front of the paintings.

Lead white was a common pigment used in the 19th century, especially in Chinese painting, and was present on many of the pith paintings. When exposed to pollutants in the atmosphere, the pigment is prone to darken and this had occurred to areas in the paintings, especially in those of flower petals. By treating the blackened lead white, it was converted to a more stable white pigment and the image was reverted back to how it was originally painted.

Mounting

Securing the edges of the paintings with silk ribbon was a traditional way of mounting pith paintings in the 19th century and so it was decided that the ribbon should be included in the remounting of the Ward paintings. Due to the brittle nature of the pith, and the fact that it moves according to humidity levels, it was important that the paintings were not adhered to the backing support in any way. Japanese paper strips were therefore used to hold the paintings in place and the ribbon was stretched across these, thereby recreating the original mounting but allowing the pith to flex and expand as it needed to.

Conservation completed

I have learnt a great deal from treating these pith paintings. Their fragile nature and unique characteristics meant that I had to adapt traditional paper conservation techniques so that they retain their vibrancy and distinctive features. I look forward to using these skills again when I treat others in the collection.

-Eleanor Hasler - (Collections Conservator)