22 December 2022

Christmas spice makes all things nice

Learn more about the spices that make Christmas such a scented treat.

'Tis the most wonderful time of the year and a festive aroma fills the air.

Pine, oranges, and a heady mix of spices all speak to the Christmas season.

Find out more about these spices and how they came to be the scents of the season.

Special spices

The East was an almost mythical land to 15th century Europeans.

Spices from these regions didn’t just have culinary value; as a result of their imaginative associations they were often thought to inflame passions, summon gods and treat medical ailments, not to mention disguise body odours!

As winter solstice celebrations merged with Christmas, wealthy Europeans wanted to show their prosperity and power by using rare, expensive spices in their festive feasts.

Nutmeg

Once the rarest of spices, nutmeg is the pit of the fruit from the Myristica fragrans tree, native only to the Maluku Islands of Indonesia.

In the 1600s, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) took control of the islands and the vast majority of the nutmeg trade, which was so lucrative they forbade native islanders from selling the pits to anyone outside the VOC on pain of death.

By 1760, the price of nutmeg exceeded 80 shillings (approximately £410 today) a pound in London.

Nutmeg’s rarity meant it was highly prized by wealthy Europeans who showed their prosperity by having nutmeg in seasonal feasts, and even carried personal nutmeg grater-boxes to whip out at social functions.

This little pit was so sought after that wars were fought over it; with the Dutch eventually trading a swampy island, New Amsterdam, for the nutmeg-producing Run Island.

That swamp is now New York City.

The high couldn’t last, however. In 1769, a one-armed French missionary called Pierre Poivre smuggled nutmeg out of the Malukus to grow in French colonies, ending the VOC’s near monopoly.

Today the world’s largest producers of this seed are Indonesia and Grenada. Nutmeg is still a staple in Christmas dishes and spice mixes, and is still quite a costly spice.

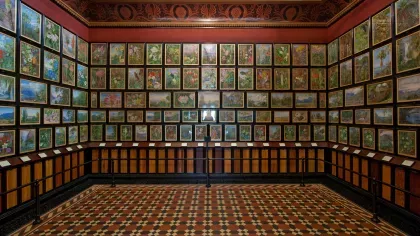

To see nutmeg at Kew, head to The Marianne North Gallery where you'll find a Victorian painting of the acclaimed spice.

Allspice

In the late 1400s, European explorers searching for pepper came across a special berry growing on a myrtle tree in Jamaica. Instead of pepper, they'd found a different spice altogether.

Unlike the name suggests, allspice is not a mix of different spices, but an unripe berry, fermented then dried, that tastes like cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and black pepper.

In Britain we tend to only cook with the berry, but allspice leaves can be used in stews, soups and sauces, and the wood is used to smoke fish and meats.

Keep an eye out for the Pimenta dioica at Kew – this allspice-bearing tree is being raised in the tropical nursery for replanting.

Cinnamon

Cinnamon has been grown and used for centuries. Ancient Egyptians used it in their embalming process, and medieval physicians to soothe coughs and sore throats.

Readily sprinkled on morning porridge nowadays, cinnamon was once so valuable that European explorers tried to find its source, which had been kept secret by Arab traders since Roman times.

This fragarant spice is the inner bark of the evergreen Cinnamomum verum tree, native to Sri Lanka and south India.

Similarly scented (and less expensive) bark is grown in other countries, such as Cassia from Cinnamomum cassia and Indonesian cinnamon from Cinnamomum burmannii.

No need to book a long-haul flight, you can see a Cinnamomum verum tree in the Temperate House at Kew.

Cinnamon’s distinctive smell is due to cinnamaldehyde, an essential oil in the bark. Cinnamaldehyde has anti-bacterial, anti-viral and anti-fungal properties.

Ginger

Decorated gingerbread creations at Christmas became a popularised tradition in the 1500s with Queen Elizabeth I wowing visitors by offering gingerbread people baked in their likeness.

As with other spices, ginger was a much sought-after and expensive commodity in Europe. Serving ginger was a display of wealth and the importance of the guests. Gingerbread was even more special as it combines other expensive spices as well as honey, and later sugar.

The Chinese have used ginger for over 5000 years to aid digestion and reduce nausea. Modern research has shown that it has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, while further studies are exploring its therapeutic and preventative effects. Pretty impressive for a knobbly rhizome!

Yes, ginger is not a root. Rhizomes are stems that grow horizontally under or on top of the soil, with nodes coming off them, whereas roots attach a plant to the ground and provide it with nutrients.

You can spot ginger plants at Kew in the Palm House.

Cloves

Like nutmeg, cloves are believed to be native to Indonesia’s Maluku Islands. They have been traded for thousands of years, and like other spices, were very rare and therefore expensive.

These beautiful spices are the dried, unopened flower buds of another tree in the myrtle family, Syzygium aromaticum. They are handpicked and traditionally dried in the sun.

Orange pomander balls studded with cloves are often made around Christmas. These take inspiration from the pomanders of Medieval and Renaissance times; orbs worn around the neck or on a belt, full of fragrant spices which not only reduced the fetid smells of the time reaching the nose of the bearer, but were also thought to protect them from illness.

In the case of cloves they might have been on to something. Cloves are anti-microbial and antioxidant. Studies are ongoing into further potential uses of this small but mighty spice.

The Marianne North Gallery is the only place at Kew where you can see cloves.

Although not as rare today, spices still take incredible journeys to get to our kitchen cupboards. Often picked by hand in tropical climes, they journey by sea to flavour, especially around Christmas, our lattes, cakes, and dinners.

Many of these plants which are found at Kew today were collected in a mission to document and trade the world’s most useful plants during the colonial era. Today’s practices are deliberately and remarkably different, focusing on partnership and collaboration with global colleagues and peers to share knowledge and resources.