25 May 2018

Celebrating the Temperate House

To celebrate the restoration and reopening of the Temperate House, Kiri Ross-Jones tells the story of the original construction of the building, which took over forty years, as told through Kew’s archives.

Beginnings

After the completion of Kew’s iconic Palm House in 1848, William Hooker, Kew’s Director, turned his attention to plants from the temperate regions that needed protection, particularly during the cold winter months. He began his campaign for government funding in his Annual Report of 1855, writing:

“what were once the pride of these Gardens, I mean the numerous conifers and the trees and shrubs from Australia and New Zealand etc.” are “suffering beyond recovery for want of suitable winter shelter”.

In each year’s subsequent report, William continued to make his case stating that the “National Establishment” could not be perfected without this glasshouse to accommodate the collections and writing about his desire to build a “Winter Garden” for Kew’s visitors. In the Archives, we hold letters to the Government from William, in which he outlined the design for his new house and made promises about it being much cheaper to construct than the Palm House.

After a discussion in Parliament, funds were finally granted, although only £10,000 rather than the requested £25,000 – Joseph Paxton had argued that the house could be built for the smaller amount! On 7 March 1859, a letter (KEW22) was sent to William Hooker permitting him to obtain plans and estimates, and Decimus Burton was commissioned as the architect.

Who was Decimus Burton?

Decimus Burton was one of the leading architects of the nineteenth century. As well as designing the Kew’s Palm and Temperate Houses, he also did much work in the classical revival style, working on London Zoo, Hyde Park, Wellington Arch, the grand terraces of Regents Park and Buckingham Palace, as well as laying out and designing the towns of Tunbridge Wells, St Leonard’s-on-Sea and Fleet.

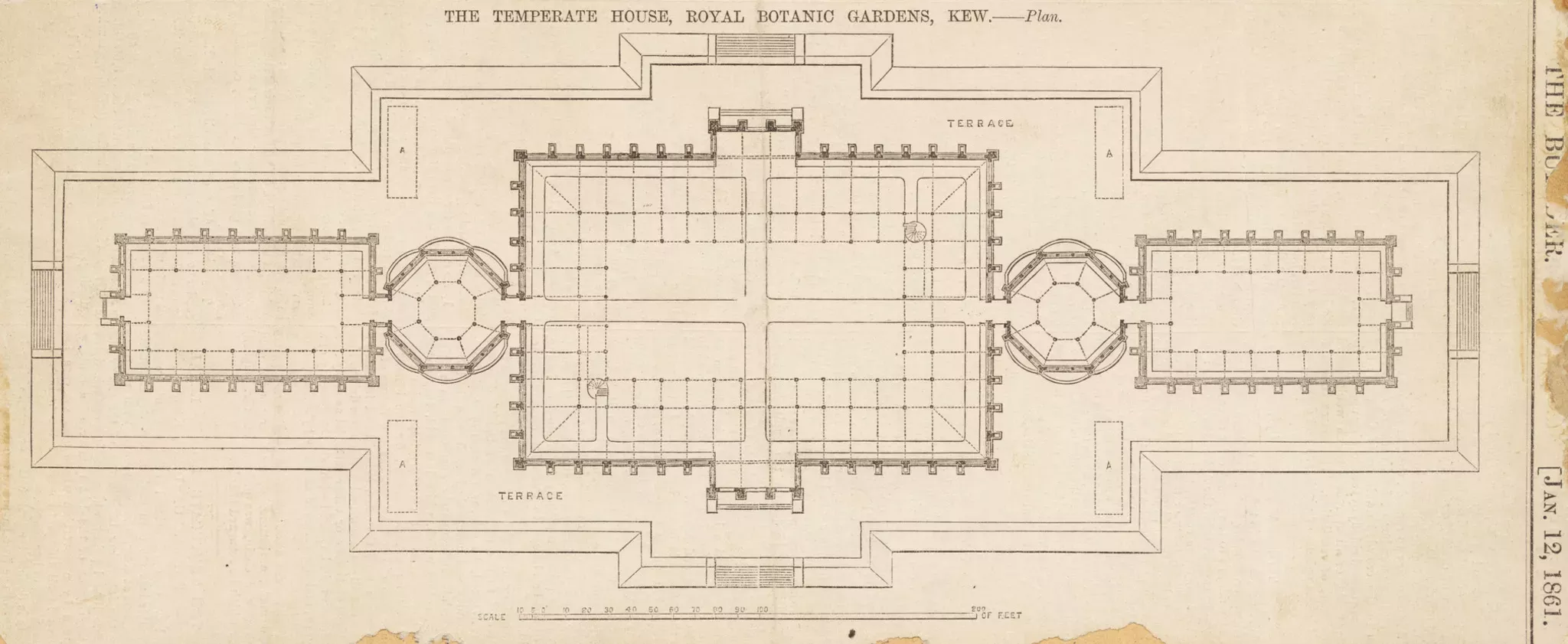

Plans

Decimus Burton designed every angle of Kew’s Temperate House, from the benches for the pot plants and pipes for the heating equipment, to the stunning octagons flanking the parallelogram at the heart of the building. In the Archives, we hold a series of thirty original Burton plans detailing these designs.

Construction

Eleven builders were invited to tender and Cubitt and Co were chosen. Construction began in 1859. From correspondence in the Archives, we can see the level of attention that was paid to the design and construction of the building.

“The Glass provided by Messrs Cubitt & Co is not according to the contract. I have forbidden that to be used & desired with the least possible delay to get other or proper tint and quality.” Burton to William Hooker 16 Nov 1860, DC/38/153

As was Kew policy at the time, green tinted glass was used in the building. The tint was meant to prevent the plants being scorched by direct sunlight, creating a better environment for them. However, it all had to be replaced at a later date, as it became clear that the plants did not flourish in the green light.

Opening

The building opened to the public in May 1863, to much acclaim. The Illustrated London News (11 May 1867) talked about the “gorgeous masses of foliage that swell beneath” the visitor’s feet, when viewed from the gallery and Garden and Forest (1892) praises the natural arrangement and robust health of the plants.

The completed building was twice the size of the Palm House and 60 ft high to accommodate the tallest specimens. At the time, it was the largest plant house in the world and today is the largest surviving Victorian glasshouse. Plants from Australia, New Zealand, Asia, Africa, Central and South America had been moved into the house, allowing the visitor to experience the flora of these regions. The central hall was divided into twenty oblong beds, containing tall plants and trees, with side beds of shrubs. Along the sides ran benches on which smaller plants in pots were placed.

However, the building was not complete, as the two planned wings that were to house the Indian and Mexican collections, were missing. In the Archives, we hold a draft of a letter sent twice to the Government by William Hooker, in August and November 1863.

“With surprise & concern I have been unofficially informed, first by Mr D Burton, & now from yourself through Dr Hooker, that it is proposed to abandon the completing of the Temperate House”

“I cannot but regard the fact of my not being consulted upon so important a step as the abandonment of this building, which completes the National Establishment at Kew, as a withdrawal of that confidence which has been uninterruptedly extended to me for nearly a quarter of a century.. and that as the natural course of events I shall not again be entrusted with so important an undertaking, I cannot conceal my deep mortification”. KEW22

Tragically, both Hooker and Burton were to die before the building was completed.

Completion

Joseph Hooker, Kew’s second Director and William’s son, seemed to hold little interest in completing the Temperate House and wrote in his Annual Report of 1868 that there were other works that were more urgent. And so it fell to Kew’s third Director, William Thiselton-Dyer to complete the house. Thiselton-Dyer began corresponding with Government in 1891 and in his letter of 20 December of that year, wrote that “the incompletion of this fine house is a chronic eyesore” (KEW22). In 1894, the Government agreed to grant the funds for the erection of one of the wings and later funds were agreed for the second wing, with both being open to the public by 1899. Finally the building planned by William Hooker and Decimus Burton was complete, forty years after it was started.

Original plans and correspondence relating to the construction of the Temperate House can be seen in two exhibitions at Kew. Historic photographs and artwork relating to the plants housed are also included in the exhibitions.